saltboiler

times

A Journal of Jackson, Ohio, for Wildflowers, Local History, and Travel

carl crawford—

ordnance sargeant in the first armored division

CARL CRAWFORD

contents—click on a chapter

- 1—farm life in west virginia

- 2—enlistment and training

- 3—shipping out to europe

- 4—north africa‚ battle of the kasserine pass

- 5—north africa‚ daily living

- 6—italy‚ and anzio

- 7—italy‚ and breakout from anzio

- 8—discharge from the army

- 9—questions and answers

My name is Carl‚ middle name’s Icen‚ spelled I C E N‚ Crawford. I took a lot of beating with that when I was growing up. Kids teased me about it all the time. I was born January 20‚ 1920 in a little coal–mining town named Red Rock‚ West Virginia. That’s near Clarksburg.

My dad worked in the woods as a lumberman. He cut timber. He worked in a lumber mill and then as I was a teenager‚ he worked on a farm. We were tenants‚ equivalent to sharecropping‚ I guess. We worked sometimes for a share of the crop and sometimes on our own‚ paying rent.

There were five children. I had one brother older than I and a sister‚ the oldest of the five and then two sisters younger than me. I was the middle one.

I attended Buckhannon Upshur High School in Buckhannon‚ West Virginia. I graduated in 1938‚ but I started the first year they had free busing and no tuition‚ so if it hadn’t been for that I might have still been down in the hills.

The grade schools were always free. For a time West Virginia did not have free high school education. Where I grew up‚ if anyone went to high school he had to move into town and pay tuition. The high school was in town. For a long time there was no bus service and few people had automobiles. Only the people that were well to do‚ had an oil well on their farm or something like that. They’d have an automobile. Otherwise it was pretty tough sledding.

I loved basketball and softball. Basketball was my favorite‚ but I couldn’t go out for practice because the only transportation I had was a bus. And at four o’clock or three–thirty or whatever I had to be on a bus headin’ out to the farm to do the feeding.

I had two years of French and I enjoyed that a great deal. I don’t think you learn English until you study a foreign language. I learned after I got out in the world that our teachers in Buckhannon were excellent. Especially my English teacher and French teachers were outstanding. I found over in North Africa where they spoke French that I could understand and I could speak very well‚ limited only by my vocabulary. So I had real good instruction there. I liked science and math‚ but I almost flunked an algebra course because there was a little blue–eyed blond girl writing notes to me. I just barely squeaked through the course.

We had no cash is what the Great Depression amounted to for us. We never were short on food. We didn’t have everything we wanted‚ but there were always potatoes and beans and we’d butcher our own hogs.

The farmers who were well to do and well situated always had some work that they didn’t have the cash to pay somebody. But they could pay ’em in produce. So if a person wasn’t lazy‚ they could get food‚ and we managed. It was tough‚ but my dad did a lot of work on so–called public works‚ either working out in the woods cutting timber or working on the sawmill. And left the farming to my brother and I when we were growing up. “Public works” meant you weren’t working for yourself on a farm. They called all the factory work‚ for example‚ public works. It was not relief‚ just any place where you were working for somebody else other than a farm was public works‚ the mines and lumber. That was a common term.

Roosevelt’s Public Works Adminstration was a little bit later. That doesn’t refer to the same thing at all. If you weren’t at home working you were on public works. If you depended on somebody else for a payroll‚ it was public works.

Where we lived was rural. I walked two and a half miles to the school bus when I was in high school. After I graduated from high school I went back to the farm because things weren’t getting any better. My dad worked on WPA after that program was started. He worked on that for a while. They were building roads‚ and they made him a foreman. They’d have a grader‚ like you see out here to move snow‚ but the rocks were put down with a sledgehammer and fellows just muscle ’em in. Prior to that‚ the roads were dirt‚ see‚ so the rock–base road meant that they were passable all year round. You see?

They’d take field rock anywhere from ten inches in diameter‚ twelve‚ fifteen inches in diameter. Just stones picked up out of the field‚ or out of a shale bank where they get ’em out of shale. They’d grade out a roadbed and then they’d lay these rocks in by hand. There’d be a gang of men working shoulder to shoulder cracking those rock up into‚ say the size of your fist or smaller. That made an all–weather road. That’s the way they were working the WPA people in that area where I was.

I don’t remember how much a worker made in a day. It was more than they’d make on a farm. I know my dad had worked for a dollar a day. He did a lot of work for a dollar a day on farms‚ but he was industrious. He wasn’t lazy‚ and he always worked. You know‚ wherever there was work‚ he was working. Some people wouldn’t work for a dollar a day. They’d just say that’s not enough money. I’m not gonna work. But he wasn’t that way.

No cash ahead. Just barely. Still‚ we always managed to get a pair of shoes. You know Loretta Lynn and her “Coalminer’s Daughter” and the shoes that daddy always managed to buy? We always had shoes‚ but we didn’t have an extra pair.

There was a story there on WPA. My father’s supervisor promised him continued employment and good times ahead if he would change his politics. He was a Republican. We were born Republicans. We wouldn’t do it‚ and it wasn’t long after that he got a layoff notice.

That work was winding down anyway‚ but we found a new farm near Clarksburg‚ West Virginia. My dad did this‚ where he was to get fifty percent of the profit and he had high hopes that things would look up there. I found myself working that farm and he was away elsewhere working. I was working it by myself. Working horses‚ no tractors‚ and I think I worked that two years. There wasn’t any profit.

I was of an age then‚ after graduating from high school. I was looking ahead and saying what’s in this? There’s nothing in it. Let’s see‚ this would have been in 1940‚ two years after I graduated and the war was starting. I think Hitler had invaded Poland‚ hadn’t he? I checked out the service and I felt that I could get into the service. I was too young without my dad and mom’s approval‚ but they told me if that’s what I wanted‚ they would approve it‚ so I went into the Army. I left my dad with fifteen acres of corn to be cut by hand‚ and he was working away from home. I always felt guilty about that. Fifteen acres is a big field if you’re looking at it by yourself.

I enlisted in Clarksburg on September 7‚ 1940. I went home and I got my dad and mom’s signature and I was out in probably within the week. We had a bus ride to Chillicothe and on to Columbus and stayed overnight. They sent me to Columbus‚ Fort Hayes‚ with some other fellows‚ and I was sworn in. I passed the physical and was sworn in at Fort Hayes in Columbus. At Fort Hayes I had three choices. At the time I went in they offered me chemical warfare or the infantry or the armored forces. I said what’s the armored forces? Oh‚ they said‚ that’s mechanized units. Tanks and trucks and stuff like that. Sounded interesting to me so I said I’ll take that. The next morning I was on my way to Fort Knox‚ Kentucky.

Fort Knox was the armored forces headquarters at that time‚ because they were just starting. So I wound up in the First Armored Division. The leverage I used on my dad and mom was that the draft was just around the corner and the following year I would be drafted. I would have been. It was true. By going in then I had some options which I wouldn’t have had if I’d have waited.

bayonet practice

bayonet practice

Basic training at Fort Knox was early morning calisthenics and then close–order drill. It was only four weeks‚ but it was tough. I guess I never felt better in all my life than when I was going through that physical exercise because it does tone up a body. I had no problems in Basic. The discipline and the sergeants‚ I expected that‚ you know‚ and kept my nose clean.

The explosive buildup in the Army hadn’t started yet‚ but it happened to us right there at Fort Knox. When I got through Basic‚ you wouldn’t believe‚ but I had a high school diploma and a lot of those guys didn’t. Anyone that was just going in usually didn’t have a high school diploma. So they reached right out and picked me and says you can type. I said yeah‚ I’d taken typing in school. So they made me a company clerk‚ which was a corporal in rating‚ right away.

Company clerk was a soft job‚ I would say‚ but it impressed me at the time. Things worsened at home. While I was in Basic I got a letter from my mom and she says we don’t have anything. She said that my dad had got hurt. He’d had an operation and he wasn’t working. She said we don’t have anything at all‚ and she didn’t know what to do. I borrowed three dollars from a friend and mailed her three dollars and she was glad to get it. That happened in Basic there. Twenty–one dollars a month is the pay I started at.

I became a company clerk‚ and I don’t know if it was at the end of four weeks‚ but it all happened closely together there. I was under twenty–one. Then the expansion hit. The buildup started‚ and they took our company‚ which the 19th Ordnance Company in the First Armored Division‚ and they made it a battalion with four companies—A‚ B and C Companies with a Headquarters Company. With the headquarters set up‚ they laid a sergeant’s promotion on me and I became what they called the correspondence clerk. I handled all the typing and there was a lot of it‚ but I was pretty good at it. This would have been in the summer‚ it would have been in the summer of ’41. This happened before Pearl Harbor. So this promotion to corporal and then promotion to sergeant came quickly. Before I went to Headquarters Company‚ I was in A Company.

Just a sideline on the way chance happens. They reached into our battalion and they pulled out one company and sent it to the Philippines. Just by chance I was not in that company. The ones that did go to the Philippines wound up in that death march‚ you know‚ where they were captured. Bataan. So I missed that by the skin of my teeth. Of course we didn’t know that at the time. They always say don’t volunteer‚ but we weren’t asked.

Our battalion did maintenance. We supported and maintained the tanks‚ trucks‚ all the mobile equipment‚ the artillery and the small arms. First echelon maintenance was something a driver would do. Second and third echelon was what we did which was unit replacement. We didn’t rebuild engines‚ we didn’t rebuild transmissions‚ but we would replace a faulty engine with a new one‚ replace a faulty transmission with a new one and that sort of things. Keep the vehicles moving. But we didn’t have the shop equipment to do the work like rebuilding an engine. Fourth echelon as they called that. We’d go back to a base unit which they didn’t have here in the States‚ but they had it overseas after we got overseas.

ordnance battalion in wwiiThe whole battalion was support to the division. Now the division had a few organizational changes during the war‚ but basically it was about fifteen thousand men in a division. Before we shipped overseas‚ they divided the division into two combat teams‚ Combat Command A and Combat Command B. A and B.

After we shipped overseas‚ the headquarters company which I had gone into because I got that promotion at first‚ they did supply work. We did the maintenance‚ but basically we carried spare tanks‚ combat ready you know‚ loaded with ammunition‚ helmets and radios and all that good stuff. So that if a line unit needed a tank‚ all they had to get is get in it and drive it away. It was ready for ’em. So we’d carry a dozen of ’em. Refurbed tanks‚ too. We got ’em combat ready. That was interesting.

Also‚ I got another promotion. The company commander called me in‚ and I can remember his words exactly. He said “Personally‚ I think you’re too damn young‚ but I need a First Sergeant.” He said “If you want it‚ you can have it.” Now the First Sergeant has a little diamond in his chevron and‚ well‚ of course I took it. It meant money and prestige and that sort of thing. But I was too young to be a First Sergeant. I got the promotion. We went through Louisiana and Texas on maneuvers. That was in the Fall‚ I guess. That was before Pearl Harbor.

The whole division went on maneuver. They were practicing logistics. Moving equipment from here to there. That’s what the maneuvers was mainly all about. And I learned about fungus and southern temperatures and weather down in Louisiana and keeping clean. I got a fungus in my crotch. I went to the medics and they gave me a lotion to put on which took all the skin off. So I had to get another lotion to heal up the skin. I learned that you don’t go in tropical temperatures more than two or three days without taking a bath‚ even if it means taking one out of a helmet. You still keep yourself reasonably clean.

That was down in Louisiana and Texas. We went back off of maneuvers and this would have been in December‚ and I was back at Fort Knox when Sunday of Pearl Harbor hit.

We knew we were in it. It was the next day‚ I think‚ the U.S. declared war on Germany. We didn’t know what to think except we knew we were shipping out‚ which we did in a matter of two or three months. We were on our way up to Fort Dix‚ New Jersey‚ to ship out. We departed from Brooklyn‚ New York the 31st of May‚ 1942. We staged at Fort Dix‚ New Jersey‚ then shipped out of Brooklyn.

We went to North Ireland. What they were planning‚ of course we didn’t know at the time‚ was the North African campaign. I remember we went into Africa in November.

Pearl Harbor was in December. In the Spring we went to Fort Dix. A large percentage of the division got jaundice. Hepatitis. It was because of the yellow fever shots. We were getting shots in preparation to go overseas‚ and I wound up with jaundice. There were so many that they made a second contingent of shipping out to Ireland. So I wasn’t with the first unit that went out to Ireland.

I went on a troop ship which was probably converted. It wasn’t merchant marine‚ I don’t think. We rode double. We had hammocks to sleep in for twelve hours‚ and then we were out on the deck or in a corner of a hallway or someplace while somebody else slept in the bunk. We rode double on that ship over to Ireland. They fed us twice a day‚ and it seemed like we were always hungry. The line to go through the galley would be perhaps the full length of the ship. So right after noon you’d have to get in line for supper. That got to be monotonous.

One of my proudest accomplishments was I stole a loaf of bread. The bakers‚ they did their own baking and the odor of that bread you know…you can’t beat how good that smells. I had a couple other guys with me and I said‚ “Let’s get us a loaf of that bread.” They said‚ “We can’t do that‚” and I said‚ “I’ve got it figured out.” Some passageways were so narrow that two people couldn’t pass each other. A guy from the bakery would have to hold a tray of bread over the top of his head because he couldn’t carry it level with his body. He’d have it over the top of his head‚ and he’d walk through that passageway.

They had these real steep ladders‚ a ship’s ladder‚ and I said‚ “I’ll go down on this ladder‚ and when he comes through you step in front of him just for a minute‚ that’s all it takes‚ and I’ll have the bread and we’ll be gone.” So it worked just like clockwork. The guy stepped in front of him‚ I reached down and took a loaf of bread‚ put it under my jacket. We had onions to eat that with. But it was good! Onions and bread.

A lot of people were seasick. I was not‚ because I was First Sergeant at the time‚ and I had a lot of details to attend to. Perhaps that makes a difference because even though the sea was rough‚ I wasn’t seasick.

I’d heard that the ship had capacity for eight thousand and we were riding double. I don’t know if that’s reasonable or not. That sounds like a lot.

We had an escort. We had a cruiser and several destroyers and no aircraft. After we got out of New York a little ways off the coast‚ there were no aircraft. The cruisers and the escort were on constant alert and they would drop depth charges every once in a while. We had no incidents that I know of going to Ireland‚ with enemy subs.

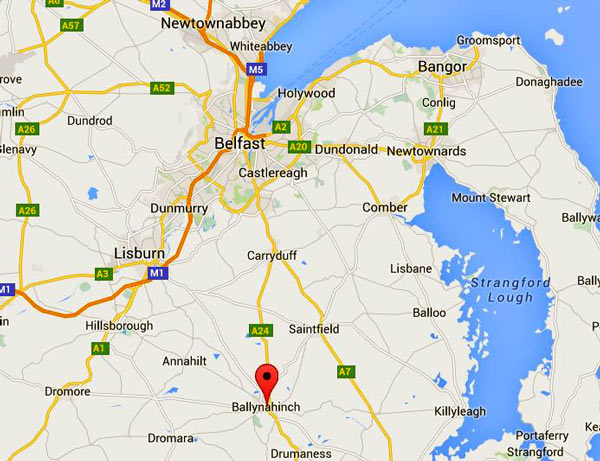

northern ireland from belfast to ballynahinch

northern ireland from belfast to ballynahinch

We landed at Belfast‚ Ireland. We docked at Belfast 11th of June‚ ’42. We went to a bay‚ I don’t remember quite the name of it. We went through a little village they called Ballynahinch. We lived in a Quonset hut‚ must have been British Army. We were on the bay where the mountains of Morne come down to the sea. There’s a song about that‚ and the natives there had a saying about the weather. They said if you could see the mountains it was going to rain and if you couldn’t see the mountains it was raining.

This was northern Ireland. We were all in there stationed in Quonset huts. We had no maneuvers. It was just staging. We went through Ireland‚ through Scotland and Wales‚ and over to England near Manchester. We staged there for a while doing nothing. Then we went back to Liverpool and shipped out for North Africa. We got into North Africa just before Thanksgiving.

But now in Ireland I got demoted without prejudice. The CO called me in. He was awful old. He was twenty–seven years old‚ I think. Captain. He told me that the Colonel—the battalion commander was a colonel— felt that I was too young to go into a theater of war as First Sergeant. So they were demoting me to technical fifth grade which was equivalent to corporal‚ without prejudice‚ and I was assigned to a maintenance platoon.

Well at the time this hurt me considerably‚ but I couldn’t do anything about it and I kind of halfway agreed with ’em‚ being too young. I mean we had seventeen–year veterans there in the platoons and what would a young squirt tell a guy like that‚ you know? After the fact‚ I think it was the best thing that ever happened to me because there I started picking up mechanical work and I liked it‚ and I moved on from there. So I didn’t become bitter or heartbroken or anything like that.

Got a Dear John letter. Had a girl in Buckhannon and while I was in Ireland I got a letter. I think it was Ireland‚ might have been Africa. I didn’t mind the Dear John letter so much‚ but she gave the ring back to my dad and my mom and I wish she’d have left them out of it.

I had a girlfriend in Ireland‚ In Ballynahinch. I had a girlfriend in England. We had dances‚ you see‚ so I’d met a girl in England at a dance. We would meet and have dinner at one of the hotels downtown. I wasn’t married at the time. It was too short‚ you know. Time passed quickly.

I think most of my buddies were accepting the war as a necessity. Certainly I did. I felt that I belonged there. In the first place‚ I’d volunteered to go‚ and I felt that we were fighting a war for survival and I was patriotic. I think most of the fellows felt the same way. We had one person who was married and I found out later that he was afraid‚ and we kind of worked around him. But he didn’t think it was his war. He didn’t think he belonged there. He had a wife at home.

I think we were eager. Good morale. There’s so much waiting in the Army‚ but everybody was tired of waiting. We wanted to get on with it.

We left Manchester‚ went back to the port. I think it was Liverpool‚ and shipped out from there on to North Africa. I was in the second group again that went down there. We had a Combat Command A‚ I think it was‚ went in on the initial invasion at North Africa. I was with the second group. The free French had already capitulated when we got there in November‚ so all of North Africa there‚ Oran and Algiers‚ was friendly to the Allies.

We went into Oran. We spent fourteen days going down from Liverpool to Oran‚ and we rode an old Canadian ship which was called the “Empress of Canada”. It was a round–bottom ship. We were going I guess you’d say south‚ and the storms in the Atlantic there were severe. That old ship just rolled constantly. We were in a storm all the time until we got to Gibraltar. That old ship rolled from first one side and then the other and I got seasick on that one. It seems like everybody got seasick. I remember one day I was sick and another fellow next to me was sick and he was supposed to stand guard duty. I said you’re sicker than I am‚ I’ll do your guard duty for you. So I did a trick of guard duty for him because he was sick.

gibraltar to oran‚ algeria

gibraltar to oran‚ algeria

Oran is on the Mediterranean Sea. It’s in the country of Algieria‚ after we went through Gibraltar. It was funny going through Gibraltar. Spain was neutral and the lights were on in the city. We hadn’t seen any lights since we left the States because Ireland was blacked out‚ England was blacked out. When we went through the Straits—there’s a strait there at the Rock of Gibraltar—the lights of the city were on. That was a sight to see. The first night in there‚ I was on guard duty again. You see I’d been broken from First Sergeant to T–5‚ so I was eligible for guard duty.

It was about two or three in the morning and a submarine hit one of the ships. It was far enough away all I could hear was the depth charges‚ but they got a ship. The next morning we docked at Oran and the survivors of the torpedoed ship came in to the dock. They unload them first and there were some nurses on board. The people would have a blanket around ’em and no clothes. Barefoot. Just a blanket‚ see. Evidently there’s not time when a ship’s hit‚ there’s not time for anything. You just have to get off with whatever you got on. They had a whole shipload of people. I don’t know if they all survived or not. We weren’t privileged to that sort of information‚ you see.

Oran—it’s a port city‚ but there’s mountains around it. Have you heard of the Casbah? Well‚ it was Arabic‚ you know. So a lot of the architecture reflected the Arabic styles. Not all of it. It had a modern section also. We didn’t stay there long. We shipped right out into the country.

The French had control of Oran. We didn’t have air superiority. The Allies did not have air superiority at that time‚ so we had daily visitations from fighter bombers and strafing from the Germans. No Stukas‚ though. They used one of the earlier Messerschmitts.

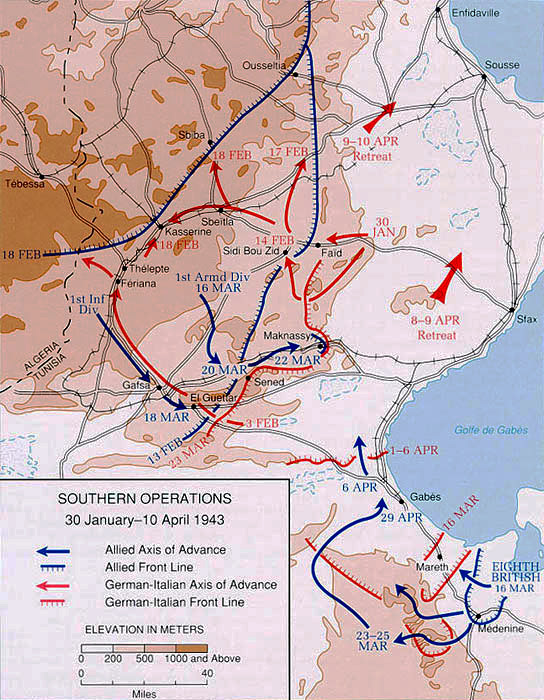

area of campaign in algeria and tunisia

area of campaign in algeria and tunisia

We had our trucks and tanks. We caught up with our tanks‚ and then we moved into the area east through Constantine and up in the area of Sbeitla for the winter. That was just before you get into the Kasserine Pass area.

A dive-bombing attack is frightening. It’s unbelievable. The first time I was in an area where they came in…you see‚ the planes scream as they dive. It makes a terrible noise. This was up in the vicinity of Sbeitla. We were in the field‚ and we had a standard procedure that we were supposed to park our vehicles one hundred fifty yards apart. That made them less attractive targets than having them ganged up together. We would park the vehicles and dig foxholes for shelter. Then we’d do the maintenance work in the field.

This first plane that came in might have been as much as a mile from me‚ but when they go into a dive and they scream‚ you swear they’re coming right at you. I thought at the time‚ hey‚ if I’m this frightened when a plane‚in a dive‚ what am I going to do when the artillery hits? But it wasn’t that bad. The artillery doesn’t give you time. It doesn’t have that screaming approach like the divebombers have. The strafing was always a risk‚ but we set up machine guns on the edge of the foxhole. All we had was ground mounts‚ but we made a game out of it. Those Germans come in‚ we’d try to get one of ’em with the machine gun. One of our wrecker crews got credit for downing one of ’em.

I never was that fortunate. I tried. I was shootin’ at ’em. I couldn’t judge the distance that well‚ he wasn’t right over me‚ but they were coming in my direction. There was a sound that I wasn’t familiar with‚ but did you ever hit the ground with a chain‚ a long chain and you know the chain doesn’t hit the ground all at once? It keeps stretching out and one link will hit and then the next one and so forth. Well these machine–gun bullets sounded just like a giant or something whooping the ground with a chain. I thought‚ well‚ he just missed me or I could have wound up with one of those bullets you know. I had my gun jammed so I couldn’t shoot at him.

.30–caliber machine gun

.30–caliber machine gun

The machine gun was a thirty caliber. Air–cooled. I wanted to hit him. I wasn’t scared. I suppose I ought to say it with reservation. At that particular location we had a rather large foxhole. It was hollowed out down below. I was up at ground level firing this gun and the belt kept twisting and jamming on me. Another guy was with me and I said‚ “Get up here and hold this belt so I can fire this thing.” He wouldn’t do it. He said‚ “You’d better get down here‚ you’re gonna get hit.” I said‚ “No‚ get up here and hold this belt.” He wouldn’t do it. You might say I was excited‚ but I wanted to get that plane.

The foxhole was big enough that I could stand up in it with my shoulders exposed. A couple of soldiers were in it. Two of us.

They had these P–40’s. American–built plane. It was American aircraft. They would come over also‚ and some of our guys got so trigger happy that they were firing at the American planes. We had some anti–aircraft guns set up nearby‚ and I wouldn’t fire unless the anti–aircraft was firing because I figured they could identify the planes. But one day one of the American planes broke out of formation and came back over the area wigwagging his wings to identify and stop the shooting. That must have been risky‚ but he figured maybe it was more risky if he didn’t do it.

We got attacked every day. Seemed like every day. It was always with us.

I was in the headquarters company of the ordnance battalion. We were organized in two combat commands‚ and we were in First Armored Division. My battalion was Ordnance‚ and we had a headquarters company and three letter companies‚ A‚ B and C letter companies.

Our headquarters company’s responsibility was to maintain the spares. We had wrecker crews also to pick up cripples‚ and we also did maintenance work. If something failed on the road our wrecker crews would go pick it up or we’d send a crew out. I became part of a maintenance crew at the time‚ and if we could fix it on the road we would do that.

We had artillery and we had the tank units and we had infantry‚ and we had engineers in the division. Actually they were supposed to be a self–contained combat unit‚ with support. We had both tanks and infantry because you usually had one supporting the other in combat. Our battalion was the only ordnance battalion in the division.

diamond–t tank transporter

diamond–t tank transporter

We kept twelve tanks on hand‚ combat ready‚ gassed up‚ and everything. We got the replacement tanks from the base units at the port of entry. We would transport the tank on a carrier‚ or drive the tank itself‚ either way. If you had very many you wouldn’t have ’em in a lowboy‚ so you’d drive ’em. The wreckers would have a lowboy available and they moved ’em both ways. Either drive ’em or pick ’em up.

These were Sherman tanks‚ with a seventy-five millimeter cannon and we also had thirteen-ton light tanks‚ with a thirty-seven millimeter cannon. The Sherman was a thirty-six ton tank. As the war progressed we had several modifications to the Sherman tank‚ but they were all Shermans. They kept improving ’em a little bit.

The Sherman was mechanically reliable‚ but nobody liked the guns. The 75-millimeter was a cannon. It was not a rifle and it couldn’t stop the German Tiger tank. The armor on that Tiger was too heavy in front. If they were fortunate enough to hit a track they could break a track‚ but the tank would still have its gun battleworthy. I’ve talked with tankers and they said‚ “We just bounced projectiles off the sides of their tanks.” They said‚ “What can we do?” They’d hit ’em and couldn’t knock ’em out. I thought it was pathetic‚ but that’s what they were facing.

We had line outfits‚ the combat teams were out on the line at the time‚ while we were stationed in Sibeitla. They were in position. At that point in time they tried to keep the support units out of range of the artillery. That changed as the war progressed. They found out the support wasn’t any good if it was forty miles back. Over in Italy we got closer‚ of course‚ but there in Africa we were pretty far back.

The line units had made contact with them and as I recall they weren’t winning any battles. It was more or less a holding type situation because the British were driving Rommel west. The main thrust‚ I think‚ was on Rommel’s units. How far east would that have been‚ in El Alamein? It was supposed to be a squeeze. Looking at the whole operation‚ it was a squeeze with the Allies coming in‚ Americans and British units‚ too‚ from the west and with the British Eighth Army coming in from the east. The intent was to beat Rommel and drive him out of Africa. That was the idea.

So the Germans had a lot of this area east of Kasserine already occupied. It wasn’t just free country that they could go into‚ but there wasn’t much action at that point. Reconnaisance planes every day‚ and these bombing runs I was telling you about. Nuisance type action. It doesn’t look like a nuisance to you if you’re on the receiving end of just one plane‚ but basically that’s what it amounted to. It couldn’t have had any overall strategic importance. One or two fighter–bombers coming over and harrassing the troops.

battle of kasserine pass

battle of kasserine pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a disaster. We were at the crossroads at Sibeitla and we had word that things were bad. We could hear the artillery and our CO told us we were going to move‚ but we didn’t have clearance to be on the road. This was like one night or early the next morning‚ and we waited all day and we couldn’t move. The artillery fire was getting closer‚ so there was some apprehension. A lot of apprehension at that point. About sundown that evening we got orders to move. We moved back forty miles.

The next day is when the disaster hit. I mean Rommel’s troops came through and just essentially wiped out our armor. The British unit helped save our neck. They came in from the north with tanks‚ and I’m sure they contributed. I’ve always had a soft touch for the British because I’ve admired them a great deal about their conduct in the war. A lot of people gripe about the Limeys‚ but I wasn’t one of ’em.

When we moved‚ we moved back forty miles. The next day it was all over and Rommel’s troops had pulled back. I guess they just made a thrust and moved back. The only way we got out of that‚ we had the Second Armored Division in Algiers staging for Sicily. The planning was all ready for Italy. Of course‚ we didn’t know that at the time. We got the Second Armored’s tanks. They just gave ’em to us. So our division was right back in action.

I don’t remember how many tanks we lost‚ but the percentage must have been high. You could say all of them. It must have been pretty close to all of them‚ because they just shot ’em up. Some of ’em were burned. There were very few of ’em that were salvageable. We picked up some spare parts from them.

We went out after…I forget what it was‚ whether it was an alternator‚ a generator or a carburetor…and we had a six by six truck.  6x6 truck with machine gun mount They’d cut the hood out of a truck and put a round railing on top of the cab of the vehicle and mounted a fifty–caliber machine gun up there. I went out with another mechanic and a platoon officer and got some parts off of one of these tanks. It was like being in the middle of the desert‚ but tanks here‚ there‚ and elsewhere. We met a vehicle‚ and we could see it off in the distance coming to us. I got on this machine gun‚ ready. I don’t know if I’d have done any good. When we met‚ got close enough to see‚ they had a machine gun trained on us also. But they were Americans. That was friendly‚ no problem there with the Germans.

6x6 truck with machine gun mount They’d cut the hood out of a truck and put a round railing on top of the cab of the vehicle and mounted a fifty–caliber machine gun up there. I went out with another mechanic and a platoon officer and got some parts off of one of these tanks. It was like being in the middle of the desert‚ but tanks here‚ there‚ and elsewhere. We met a vehicle‚ and we could see it off in the distance coming to us. I got on this machine gun‚ ready. I don’t know if I’d have done any good. When we met‚ got close enough to see‚ they had a machine gun trained on us also. But they were Americans. That was friendly‚ no problem there with the Germans.

One of our wrecker crews and a maintenance crew was out in a halftrack‚ and they got cut off by the Germans. The Germans kept the driver of the halftrack and they took their wristwatches‚ but they sent the rest of ’em walking back through the cactus patches. They had cactus over there in North Africa. They sent ’em walking and they came back safely and the fellow that they kept wound up in a prisoner of war camp. We got word from the States from his folks that he was safe in a prisoner of war camp. Not all of the Germans were brutal‚ not at that time.

The burned and destroyed tanks were relatively close together‚ I would say. Maybe a hundred yards apart‚ maybe two or three hundred yards apart‚ a lot of ’em. But one would have a gun pointing in one direction‚ another would have a gun pointing in the other direction. Another might be in another direction. They were not in formation.

I heard stories about one colonel leading a unit of tanks. He saw the tanks were retreating and he got out on top of a tank‚ like General Patton‚ and waved his people back into combat. But the trouble wasn’t the command. They put these tanks up against the Tiger eighty–eight millimeter guns that just punch a hole in the Sherman tanks‚ but the Shermans couldn’t knock the German tanks out. Those Tigers could just pick ’em off one at a time‚ like shooting ducks. So the big lesson they learned there was that they didn’t go up against the Tiger tank. When they located one they called on artillery or the Air Force to hit it. They started using tanks with some discretion.

The artillery was more powerful. The artillery was so accurate. It’s just amazing how accurate the artillery is. The trouble with the tanks as what I saw and what I heard from the tankers that I talked with‚ was they were simply undergunned. They didn’t have a gun that was a match for what the Germans had.

Sometimes our tank crews bailed out and sometimes they didn’t. I’ve seen ’em where they were burned up. The tank burns up immediately. Why‚ they don’t have a chance to get out. It’s a funny thing. The tankers want no part of the infantry and the infantry want no part of the tanks. So it’s a matter of what you’re trained for‚ I guess‚ or what they’re used to.

The word was out there that the Americans had good equipment and the Germans just pulled up and quit when they faced the Americans. It didn’t turn out that way at all. We used the tanks contrary to what we later learned was good battle tactics‚ and that was primarily the cause of the Kasserine fiasco‚ I think. They replaced the division commander after that. Sent him back to the States and we got another.

I’m not sure of first commander’s name‚ but MacGruder was the replacement. Major General MacGruder‚ and when he took command he called an assembly‚ a whole division in a natural amphitheater. He set up a P.A. system‚ and he gave us a pep talk about how poorly the division had done as a result of the command. That he was going to turn things around. That if he couldn’t do it he’d step down and let somebody else do it. Would you believe the GI’s booed him? I never heard such a thing‚ GI’s booing a general. And they got away with it. Everybody knew how badly we did in the battle‚ but I guess it wasn’t the thing to talk about

You might call it a training ground. The American commanders and strategists learned an awful lot in Africa. They put it to good use later on.

We had artillery units either in the corps or else they were attached to the division. We had some 155 millimeters‚ which is a big rifle-type thing‚ in Africa. The division artillery was for the most part these 105 Howitzers. Their range is several miles. They would try to camouflage them‚ so I don’t know how close they would be. They didn’t want to expose themselves to the Germans. Over in Italy‚ where we had more of a holding engagement‚ they used smoke to keep the Germans from seeing. Put up smokescreens. The artillery… whatever the range is‚ they’re accurate. If it’s ten miles‚ it wouldn’t matter whether they were ten miles or five miles away‚ they could still destroy a target as long as they’ve got a spotter or somebody to call the shots. They had those people with the line outfits‚ right up with the infantry and the tank units.

After Kasserine‚ the British Eighth Army was pushing from the east. They destroyed Rommel’s forces there and they met up with the Allies in the area of Sibeitla. Then the whole group moved to the north to Tunis and Bizerta. That was the end of the Germans in Africa.

We drove all the way back to Casablanca. Not on the train; we drove those doggone trucks all the way back to Casablanca. We staged there for Italy. As I recall‚ it was summer when we were in Casablanca. Then after Casablanca we went back up to Algiers and shipped out to Italy.

We were staging in Casablanca. We were there from the time the campaign was over until we drove all the way back up to Algiers and shipped out to Italy. It was just staging there. We had some of our units there‚ I know‚ because we had work to do. Mainly it was spit and polish. We had to wear helmets and fatigue uniforms. That kind of ticked us off. We’d see pictures of people over in McArthur’s outfits wear nothing‚ and here we were in the heat and had to wear full work uniform. We didn’t like that.

We found Casablanca friendly. I only got to Casablanca one time. They had good beer there and they were close to Rabat which was the capital of French Morocco. They were all friendly to the Americans. In Rabat‚ I was there on a Fourth of July parade. And they had the sultans.

While we were in Africa we were on our own‚ usually a pup tent or we might simply roll a bedroll under a tarp. There were no organized tent cities or anything like that. We were with our vehicles. We had maintenance trucks. I wasn’t a wrecker driver‚ but we had wreckers and we had shop trucks. When we first went to Africa‚ we might only have a three–quarter ton pickup–type truck‚ that you could carry tools on. Later on I got a bus–type truck specialized for electrical maintenance. Over in Italy I got that.

In Africa the significant thing‚ I think at the time and also looking back on it‚ is the Allies did not have air superiority‚ so we were subject to harassment on a daily basis by German fighter bombers‚ as we called ’em. They’d come over with a couple of bombs attached‚ one on each wing. If they could find a target they’d drop the bombs‚ then they’d make a strafing run with machine gun fire after that‚ come back over the area with machine guns. So we always had the foxhole for shelter when we would work on a vehicle.

The work was in the field. We had a truck for equipment and tools and that sort of thing‚ but if we needed to change an engine it was just pull a tank in the area and use a wrecker to hoist the engine out and put the new one in. It was all done in the open.

We were pretty well situated in Africa. We didn’t move very much because it was a holding situation at the time we went in there. Wherever the division went‚ we went‚ see. But they weren’t going any place. Really they were waiting on Montgomery to drive Rommel back through that area. That was the purpose of it.

We did have a chow truck‚ a kitchen truck. They would feed us three times a day and of course that meant a chow line. It always seemed like there were lines in the Army. If a German plane came over at chow time‚ everybody scattered and it wasn’t uncommon for people to jump in a garbage pit for shelter. They did that when the fighters would come over.

Food was good American food the most part. When we first landed in Africa‚ they had us on British rations. We got a lot of goat stew. Goat stew. They said it was British and so it wouldn’t have been local. It was canned. I don’t know where the British got their goats‚ New Zealand or wherever. But we didn’t think much of that. We never suffered for food after the initial landing. On the first landing there we only got fed twice a day for a while cause rations were short. But that didn’t last very long. I told you last time we went in in November‚ just before Thanksgiving. They made a special effort and served us turkey for Thanksgiving.

Each company would have had its own kitchen trucks‚ kitchen equipment. In our battalion we had three. Our three letter companies and the headquarters company‚ so we would have had four kitchen trucks. The cooks prepared food at a company level. Served a lot of powdered eggs. I liked them. A lot of people griped about ’em‚ but it was like a scrambled egg and I never complained about the powdered eggs at all. Plenty of food.

In Africa the weather wasn’t too bad except in the winter. It rained a lot in the winter. We had snow. It wasn’t unlike the climate here in the winter‚ and we’d often have some snow. Disappear in a day or two. But in the summer it was hot in the daytime and cold at night.

Have you been to Arizona? Africa had sparse vegetation like some of the desert areas in Arizona with some scraggly bushes of some kind‚ two or three feet high. Then occasionally in the lowlands or ravines there would be some forested area. The soil was mostly sand. I don’t recall getting any sandstorms‚ but it must have been there.

The sand was a problem with maintenance‚ but our equipment was new. We had good equipment. We were not in the worn–out phase of equipment like we ran into the Germans later in the war where they had a lot of junk. Our stuff was new and in pretty good shape. Now we had damage from shipment in across from the States. They’d have salt water in brake drums for vehicles‚ and often we’d have to go in and redo the brakes because of salt–water damage from shipment across the ocean.

We didn’t pay any attention to an eight-hour day or anything like that. When there was work to be done we did the work. Of course there were no lights at night. Everything was blacked out at night. We worked as long as we could see and as long as there was work to do.

We did set up camouflage netting. That was an irritation‚ but necessary. When we put up a truck we’d have to put the camouflage net over the truck.

We worked with crews. Usually about three men in a crew. It was not a rigid thing because we had the same setup as any army unit. We had platoons and we had a maintenance platoon. I was part of a maintenance platoon. As I recall we might have had three maintenance crews in the platoon‚ and I turned out to be one of the crew. I was part of one crew and later on I got a promotion. As a Sergeant I was in charge of the crew. So we were quite flexible in that respect. For example‚ if we needed more men than were in one crew‚ why we’d just move another crew into the same job. And they would work on it.

wrecker truck

wrecker truck

We used the wreckers for hoisting and most of the six-by-six trucks…we called ’em six-by-sixes because they had front-wheel drive and a dual drive in the back and nearly all those trucks had winches on the front. We had plenty of hoisting equipment and we had winches‚ too. We never got stuck that we couldn’t get out of some place with all the equipment we had. We would have what they called a fuel dump. It was usually father back and the gasoline that we got was handled in five-gallon cans. They’d take a truck to the dump and fill it with cans and we’d take as many cans as we needed.

In Africa we used British gasoline and the octane was much lower than the comparable gas in the States. We had to reset the ignition timing on the tank engines and the truck engines to accommodate that gasoline. The Germans were to the east of us. We had Oran. We had sea shipping through the Straits of Gibraltar to Oran. They would truck the gasoline in from Oran. I don’t know where the British got the gasoline‚ but notoriously it was low on octane rating. We learned a lot about timing engines.

It was just like any unit. We had buddies. We were in the First Armored. We had people predominantly from Ohio‚ West Virginia‚ Kentucky‚ Tennessee and Indiana. Now‚ there were exceptions to that and I remember one guy from Southern Cal. He’d had a couple years in the university. We had some people from Missouri‚ but we had a lot of hillbillies in our unit. Yes‚ we had buddies. You learned to like some. You learned to dislike some. You avoided the ones you disliked and hung together with those that you liked.

We hauled water. Hauled water all the time‚ in these little trailers‚ like a little two-wheel trailer that was hitched behind a six-by-six truck. The company would have a water trailer. Probably on a company basis. They would go back in the base area someplace and get the water. For all I know it might have been all the way back to Oran‚ to Constantine or someplace like that. From a city.

We had no field showers. You had to bathe out of your helmet. The lesson I learned in Louisiana and Texas was enough for me. I think we all learned that you go two or three days and then you have to take a bath for sure. When it’s hot you would do that. In the wintertime it was mud‚ but in the summertime it was sand and dust and insects. We had to look out for scorpions. You’d roll the bedroll‚ a scorpion during the day would get into your blankets. You’d have to unroll ’em and check ’em out at night to make sure there were no scorpions in ’em.

Our latrines were slit trench. Just dig a little ditch in the ground. In theory there would be a shovel handy‚ each person was supposed to throw a little scoop of dirt over the refuse when they were finished and that was it. People dove into the slit trenches when the fighter-bombers came over. Wherever you go for cover. I never had to‚ but there were stories about it.

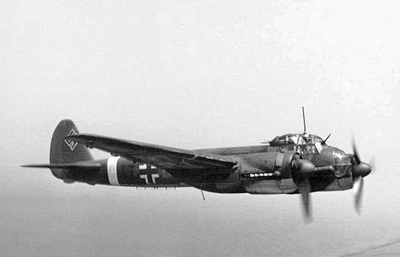

We were bored with waiting because a lot of times there was no activity‚ so you’d be bored with waiting. There was apprehension of course about the air strikes‚ even though looking back on it you can see that they had less strategic value than they did harassment. That’s basically what they were. We had poker games at night sometimes. Set up a tent and black it out and have some poker games. Friendly games‚ twenty–five cent limit‚ stuff like that. We learned to tell the difference between the German bombers and the Americans. The Germans were in diesels.  junkers ju–88 bomber They had these big‚ at that time they were big‚ Junkers. They called ’em JU ’88’s. It was a twin–engine bomber‚ and you could tell the sound of that engine‚ wherever you’d hear it‚ you could tell that that was not American.

junkers ju–88 bomber They had these big‚ at that time they were big‚ Junkers. They called ’em JU ’88’s. It was a twin–engine bomber‚ and you could tell the sound of that engine‚ wherever you’d hear it‚ you could tell that that was not American.

What we’d get would be the fighter–bombers. Occasionally we’d see flights of these bombers going over. Now there was an airport down south of Sbeitla and the Germans liked to target that airport and that’s mainly where we saw the formations of the Germans bombers going.

Occasionally it was a morale booster when we would see the American bombers going the other direction. We liked that. You know we weren’t too close so there was no concern about artillery in Africa. Just the fighter–bombers and the strafing.

I suppose every individual wonders about what their own personality is made up of. I thought as frightening as the fighter–bomber was when it goes into a dive…no matter where it’s at‚ if you can hear it‚ it sounds like it’s coming right at you. I thought well‚ gee whiz‚ I’ll go to pieces when we get into artillery fire‚ but it wasn’t that way. Artillery was…it’s over too quickly. There’s no comparison with the artillery and a dive–bomber that I could see. The dive–bombing is far more terrifying than the artillery.

Artillery is over quickly‚ but you hear that scream as a plane goes into a dive and you think hey‚ she’s coming right at me. But you know what I experienced here was I was scared‚ but I always did my job. That’s the way most of the fellows were. We had a saying if a person wasn’t scared they were stupid. But the main thing was to do what we were supposed to do‚ which we did‚ for the most part. I only had one individual in particular that I mentioned to you that was useless on a detail. We quit taking him out on details because he was too frightened.

We got more of this over in Italy than we did in Africa. But either go out on a specific assignment to go to a specified area‚ usually some officer would take us to where there was a vehicle knocked out or something‚ where we were supposed to pick it up. Or we would go to a collection point which was just like putting us out to a crossroads to take a random shot at any trouble that was experienced by the line outfits as they were moving through. That’s the sort of thing where every man was needed‚ and we just learned to steer away from this one guy that you couldn’t depend on. He couldn’t even play poker.

So the highlight of the African thing for us‚ I guess‚ was dodging those fighter–bombers. After Kasserine we picked up some spare parts from some of the tanks that were knocked out‚ but most of ’em were burned so there was little that was of any value.

We worked all the time‚ seven days per week. There was no time off. We had some Jewish people‚ a few. I remember one or two in our outfit and we bitched a little bit because it was Army policy that whenever possible they would be given time off for Jewish holiday. Religious holiday. That kind of ticked us off a little bit. But then it wasn’t all that bad because the one guy that I knew‚ he would do K.P. on Christmas Day‚ things like that see‚ so it was a two–way street. It wasn’t a problem at all. But there was no time off for any of the GI’s‚ other than the religious holidays. Methodists don’t have religious holidays.

I wasn’t a wrecker driver‚ but we had some stories by the wrecker drivers. I was working shoulder to shoulder with some of the wrecker crews. They would go out at night to avoid the German aircraft and they would pick up a tank and bring it back. Most of the time they would just tow ’em behind a wrecker. Now if the track was broken‚ a crew would fix that track as soon as they got there. If the tank was in a minefield‚ they’d pull it out of the minefield and then put the track back on it and drive it. If a tank could be driven they would drive it. It was easier to do that.

If a tank hits a mine it will break the tread for sure. The track was a steel pad covered with rubber molded on it so it would keep the steel off of the asphalt roads or off of the concrete roads. That work was heavy. You had to have the heavy–duty winches and the air wrenches and what–have–you to handle those things. We learned to use the winches and cables. For example‚ to put a track on you had to loosen the adjustment mechanism so that the track would go around the wheels on the vehicle. The little wheels that run on the ground‚ they called those the bogie wheels and then the sprocket. You’d have to loosen an idler on there so that the track would go around there. We learned that we could loop a half–inch cable around these tracks in a particular way and put a winch on it‚ and we could winch those tracks together without going through the ritual of loosening that adjustment mechanism. That speeded up the process of putting a track on.

I don’t think I answered your question about how many tanks we picked up. I don’t think I could do that. I couldn’t tell you‚ but if there was any to be had‚ why we went out and got ’em. Our wrecker crews would go out and get ’em and if there was a repair required‚ why then the mechanics would do the repair job.

We were able to keep up with the work. Of course the line outfits didn’t wait for that repair. If we picked up a tank from ’em they took another one out because we had ’em battle ready.

To transport the tanks across the ocean‚ they would drive them onto the ship. Well‚ the ships I was exposed to they would drive ’em on‚ like the LST’s. Moving all the way from Oran to where we were‚ they might have brought ’em on lowboys. Instead of miles to the gallon the tanks went gallons to the mile‚ so they preferred not to drive ’em long distances if they didn’t have to. When we had ’em battle ready it meant that the artillery was checked‚ the small arms were checked‚ and by checked I mean they were checked by mechanics‚ not just looking at a gun saying that it was all right. They were checked for head space and they were test fired and they were ready. Then the tank was fully loaded with ammunition. We did that. They were gassed up. The Sherman tanks had five crew members‚ so they had five helmets with the earphones in the helmets. So they were really ready. A tank crew could get in a tank drive it away from our outfit.

ordnance maintenance truck

ordnance maintenance truck

The table of organization changed and we were assigned in headquarters company an electrical maintenance truck which was a large van on a six-by-six chassis. It had a generator. It had an extra engine mounted for an alternator‚ a generator and had electrical test equipment to repair and test the starters and voltage regulators and generators that were on the tank and truck engines. Just like going into an automotive shop today‚ automotive electric shop. You’d have all kinds of test equipment to test the electrical components that we were up against. They picked out four or five of us and sent us to a school. The guy teaching the school‚ the object was to learn how to operate that truck. He was an electrical engineer‚ and I thought he was the smartest man I’d ever seen.

I was so interested in that‚ and I said‚ “This sounds like this would be a good career to be into.” He said‚ “Oh it’s nothing unless you have a decree.” I said‚ “What’s that?” How dumb I was! He said‚ “Well‚ you go to college and you finish four years in college‚ and you get a degree in electrical engineering and then you’re ready to start.” “Well‚” I said‚ “I’ll just do that.”

They must have taken a shine to me because of the group that went to the school‚ I was assigned a truck and then I got a promotion to a Buck Sergeant’s rating. I was making a comeback from a Technician Fifth Grade to Buck Sergeant. I think the basis for that was I was doing I did the best I could. If I were digging a ditch‚ it would be a good ditch. It wouldn’t be a makeshift ditch.

This electrical engineer was an enlisted man. I don’t know his background‚ why or how he got in the Army‚ but he had a degree in electrical engineering. That’s what first sparked me to study engineering. Also I started an allotment‚ sending money home to savings for college tuition. In the meantime they passed a GI Bill‚ so I found it pretty easy to go to college when I got back.

Africa was a shakedown territory. It was the first exposure of the Americans to the war‚ and the word was out that our equipment was good and all we had to do was show up there and the Germans would fold up and we would have ’em. It didn’t turn out that way.

We had a major who was all mouth. He told his wrecker crews—he was responsible for part of the maintenance—he says you stick with me and I’ll get you through this. Words like that you know‚ all the pep talk. They had to go out one night to pick up a tank‚ and of course when they did that they had to go to where the tank was knocked out. That meant the tank would be here and the Germans would be there. I mean they’re close so they had to go quietly and they had to go in the darkness. This major just went so far with them and said “All right‚ I’ll wait here. Now you guys go get the tank and I’ll be here when you come back.”

They never got over that‚ and it wasn’t long after that he was shipped out back to the States. I don’t know if the CO found out he didn’t have what it takes or what‚ but things like that’s what people were going through‚ you know. The difference between talk and being willing to be exposed where it counted. That’s what was happening in Africa from what we could see. They learned that the ordnance‚ as they called us‚ maintenance‚ was too far back. It was a concept of the division that for the maintenance to be of any value it had to be right there where it was needed. So in Italy there was a complete turnaround and we were wherever the maintenance was required from then on.

We were under George Patton’s command‚ I’m sure. The spit and polish was between the time the campaign was over with Rommel‚ when the Germans were out of Africa‚ and when we were staging back to Casablanca and back up ready to ship out to Italy. That spit and polish was ferocious. It was terrible.

At the time‚ we were required to wear coveralls‚ sleeves rolled down and a helmet liner. Not the steel‚ but the helmet liner‚ when we were working on the equipment. This was in the summertime in the heat of North Africa when nearly everybody was taking siestas in the afternoon. We had to wear that full uniform. Then we’d see in the Stars and Stripes where the GI’s with MacArthur in the Far East‚ would be stripped to the waist‚ and we didn’t like that very well. I don’t know of anybody that liked spit and polish. I don’t know what it contributed‚ really. I don’t know that it mattered very much. I can’t see that it did.

There’s a lot of personal things‚ maybe human interest things. The civilian population in North Africa was friendly to the Americans so even though we stood guard duty‚ they weren’t interested in sabotage or anything like that. They’d steal clothing. Anything they could steal.

The Arabs would steal that stuff‚ but they were friendly and that’s a big help‚ not to be threatened by snipers or civilians. After Kasserine we went to Tunis and Bizerta and as we went north the poppies were in bloom‚ just acres and acres and acres in the wilds there. Because this is not desert country up at the coast. These poppies‚ of course‚ would bring to mind the poem about World War I. Do you remember who wrote that poem‚ “In Flanders fields where poppies grow…?” It was a sight to see all those poppies growing.

We saw‚ by that time‚ winter and most of the summer in Africa. We felt like veterans and we saw infantry divisions from the States. They’d come in and they had orders to dig in. Every evening when they stopped‚ the first thing they had to do was dig a foxhole. Every man. We’d see ’em there digging and we laughed at ’em. There wasn’t anything to dig in from at that point. Because the Germans were gone. They still made those guys dig in. That was something.

I was impressed with the British Eighth Army troops that came through. When their tanks met up with ours‚ they looked like gypsies. They’d have blackened cookpots tied here‚ there‚ and elsewhere around the tank. I think I saw some chickens tied on a tank. Whatever they could pick up would be attached to that tank. You could see they didn’t have the spit and polish rules to put up with that we had.

I heard stories. One fellow we had was attached to some Eighth Army units. He was there as a tank specialist and been sent over there before the Americans were in it‚ I guess. He told about the spunk that he saw among these British soldiers when they were being attacked in the dessert‚ far to the east of there. He had nothing but kind words for ’em. I felt the same way. From what I saw of them‚ the British were in there doing their job‚ whatever was required.

Most of our difficult times outside of Kasserine was over in Italy. Not that Kasserine wasn’t difficult—it practically wiped us out‚ but they replaced the tanks with the Second Armored tanks.

Then we got to see a little bit of the population when we went back to Rabat. You know Rabat is the capital of French Morocco and it’s no longer French Morocco. They have their independence. They’ve had their independence for about thirty years. There was one incident that impressed me back there. Did I tell you about the 4th of July celebration?

I did have a pass and went to town there because there was no duty. I saw the Sultan’s guard. They had these dapple–gray Arabian horses‚ at least a dozen of them. They were spirited; it was really a sight to see. They came down the street along with some vehicles and other things. There were two teenaged boys standing on the sidewalk that didn’t take their hats off when the American flag went by. There was a French army officer just walked up to them and he made one pass with his arm‚ with his hand and he knocked their hats off. Both of ’em with one swipe. Then on the backstroke‚ backhanded‚ he whacked both of ’em in the face. I thought‚ boy‚ that’s something we’d never see in America‚ an army officer striking a civilian. That always impressed me.

I didn’t tell you about the girlfriend. You need to know that‚ I guess. We went to Rabat. We could get a pass and go into the city. I went in there with my platoon sergeant one day. We were in a park‚ and there was a girl that was friendly. I could manage a bit of French because I had two years of French in high school. We talked and went for a buggy ride with my sergeant and I made a date to see her again.

I’d go back in there to see her. I didn’t have a pass‚ but I would go AWOL. There were no duties at night. The French soldiers were wearing American uniforms—khaki uniforms—with a black tie. It was the only difference‚ just the black tie. I don’t know where I got the black tie‚ but I did something that was very foolish‚ looking back on it. I got rid of all my identification. Can you imagine that in a foreign country? And would go to town and step beside a building someplace and put a black tie on. And stay past curfew because they had a curfew there for American soldiers.

I’d go see that girl and then go back on the road. There was always a lot of traffic‚ and I’d hitchhike back to the outfit. I got away with that. Her name was Andree le Denmat‚ and she lived on Boulevard de Kebibat. She would meet me in the neighborhood near her house and then go to her house. She had a little sister. They loved to hear about American movie stars. Just crazy over that. So I had a few enjoyable hours with a girl.

I wrote her a letter once or twice after we left. I did that partly for orneriness because I knew the officers were censoring our mail. You know it was customary and a requirement that all enlisted men’s mail had to be censored. I wrote this letter in French to the girl in Africa. I don’t know if it ever got there or not. I wrote that letter just with… I guess the devil made me do it. I chuckle to think what the censors might do with it.

We didn’t see the German prisoners in Africa. They must have kept them east of where we were. I don’t know whether they surrendered to the Americans. In Italy we saw lots of ’em‚ but not in Africa. We saw a lot of Italians in Africa because they gave up early in the campaign.

We left Tunis and Bizerta and went to Rabat, then we went back to Algiers. We shipped out of Algiers to Naples. Algiers is just like the pictures. I mean it was‚ at that time it was a beautiful city. They also had what they call a Casbah which is an old‚ old native quarter. The streets may be only about eight feet wide. Three or four of us walked through the Casbah one day up there. We were kind of leery you know of going into places like that.

I went into Naples. I was on a Liberty ship. I told you I thought it was Africa when I got that truck? I know it was because I had it on the ship when I went to Italy. We were on a dock where there were five ships. There were two ships lengthwise on each side of the dock and one ship crosswise on the end of the dock. The space on the dock in between the ships had room to drive trucks around adjacent to the ships. The area between that space was filled with fifty–five gallon drums of gasoline. I didn’t like that.

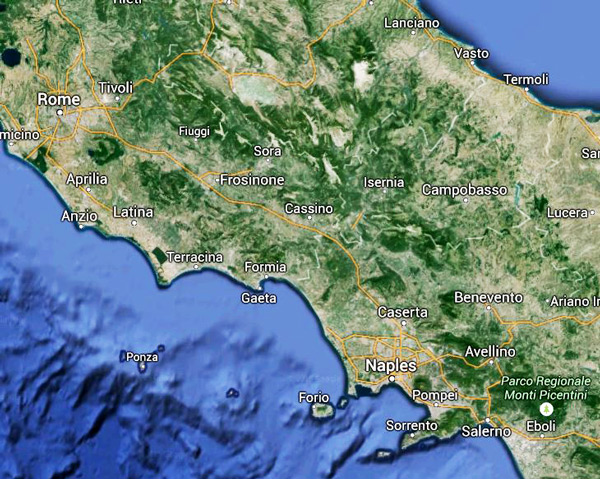

map of italy‚ naples to rome

map of italy‚ naples to rome

The first night that we docked there I was sleeping on a deck and just about dusk a German plane came over. Sirens started because the Allies were already there. We were not the first ones into Naples‚ you see. The other contingents of the division had already landed down there. They had smoke generators. So the sirens started and they put up smoke. The bombs didn’t hit close to us that night. They had the anti–aircraft fire.

To another fellow that had an automotive truck‚ I said‚ “Let’s not stay on this ship another night.” He said‚ “We have to. We have to wait till our trucks are unloaded.” I said‚ “No‚ we don’t because I paid attention to what happened when the alarm sounded. They had a guard on the gangplank. He took off.”

The guard had left. Also‚ they never prevent anybody from coming on the ship. They just wouldn’t let anybody leave it. Anyone could come on without any questions asked. So I said‚ “You get a blanket ready.” This was the second day‚ and I said‚ “If that alarm sounds‚ we’ll just go down the gangplank and we’re home free.”

We went up in the harbor and it happened just that way. The alarm sounded. The plane came over. The smoke generator started. We took off down the gangplank and went up the dock area away from this gasoline. There were air–raid shelters there. We went into an air–raid shelter and spent the night. The next day we put a blanket under our arm and went down there and walked up the gangplank just like we owned the place. A guard was there‚ no questions asked‚ see. We got our trucks off that day. You know a hit there‚ and there would have been nobody got off of any of those ships with all that gasoline on the dock. It seemed kind of silly.

They were working the… we called them paisans. They worked ’em eight hours‚ cleaning that stuff out of there‚ getting it out to the dumps. That ticked me off because we’d been through Africa working as long as there was work to do‚ you know‚ and then see ’em work eight hours and quit with gasoline still on the docks. That kind of ticked me off‚ especially when I was there.

Some of the crew members stole my field jacket. A field jacket was a little light poplin jacket and they cost seven dollars and a half. Even though it was a theater of war I had to pay for that jacket. I had nothing to wear. I was stubborn‚ so I held out for a long time. I kept after the supply sergeant to give me a jacket. “I’ll get you one anytime you sign a statement of charges.” I wasn’t going to do that. So I worked in my overcoat that winter for a long time. Finally I threw in the towel and signed a statement of charges and they took seven dollars and a half out of my pay.

After we unloaded from the ship we went somewhere out in the country‚ not too far out‚ and set up shop‚ and that was it. We spent the winter there‚ it was mud‚ mud everywhere because it rained a lot. This was while the action was on up at Monte Cassino. Some terrible encounters were taking place up there‚ but there was no movement‚ you see. Again it was just a holding action.

Yeah‚ they were in I forget the name of the river‚ but here’s Cassino‚ right here. That must have been where the abbey was. That was a holding point that they couldn’t break. You’ve seen the movies of it‚ I presume‚ haven’t you? While that was going on‚ everything was just dug in. There was no mobility and there was very little for us to do except live in the mud. I recall we slept in pup tents again and you couldn’t get away from the mud. You’d take wet shoes off at night and put wet shoes on in the morning. But the civilians were friendly again. The Italians had already capitulated so we didn’t have to worry about the snipers in the civilian population.

There wasn’t anything for the tanks to do because they weren’t moving. They probably had some of ’em dug in using them as artillery‚ but it wasn’t tank country up there. We had very little to do but wait. Now what I didn’t know was of course they were already planning Anzio. You’ve heard of the Anzio beachhead?

Vesuvius. We were seven miles from that. We were in Naples on what they called Palace Hill‚ and we were staging there to go up to Anzio when that thing let go. The eruption lasted for three or four days‚ something like that. When it started to cool down‚ seemed like about every fifteen minutes there would be a loud explosion just like a cannon or louder than a cannon. I had the impression that a bubble of gas or lava would build up in the crater and then it would ignite and explode. This was so regular that it became monotonous. Day and night‚ just every few minutes that thing would let go with that loud explosion. Of course I’d read about Pompeii. See‚ Pompeii was just a few miles south of us there on the coast. You always wonder if those things are going to behave or whether they’re going to be disastrous‚ the volcanos. At least I always did.

We were in Naples staging in the early Spring and shipped out to Anzio. The landing was made and I think there was about four weeks of the beachhead yet when I went in. We had ten miles coastline and seven miles in depth. It was about four weeks before the end of it. When I went in there‚ a lot of the severe fighting was already over. I took a tank up there. One of our officers lined us up one day and he said‚ “I need ten tank drivers.” I said‚ “Well‚ I can drive a tank.” I was bored. So‚ “I can drive a tank.”

I volunteered for that and well he says‚ “I’ll tell you what I want. We’re going to Anzio. Everybody’s going anyway‚ but we need to move ten tanks.” The other fellows volunteered. I felt better taking a tank up there than going off a ship not in a tank‚ because everything is under artillery fire. Fortunately we got up to Anzio and got unloaded and went out in the country somewhere and we didn’t draw fire on the beach that day.

The whole front of the landing ship comes down to form a ramp‚ and you just drive off. We drove off and never stopped. We kept right on going. There must have been somebody to tell us where to go‚ but I don’t recall. All we had to do was follow our own leader and we went out. I don’t know how far we went‚ but I showed you one of these pictures of the first day at Anzio where everybody there lived in dugouts. We just moved into our camp area and there were already dugouts there and I found a vacant one and moved into it. All it was a hole in the ground with dirt over the top of it. Just crawl down in there and roll your bedroll out. That’s the way it was.

The big war experience for me I guess was Anzio‚ living in the dugouts like World War I. The only thing we weren’t being shot at by small arms‚ but we could hear the artillery all the time. The small arms fire‚ we could hear that. Learned the difference between a German machine gun and an American machine gun. See‚ the Germans are very fast. They fire a lot more rapid than the American machine gun. The German gun would just chatter. The American gun goes bang‚ bang‚ bang.

I don’t really know how far behind the lines we were because I didn’t have maps and I didn’t know where we were on the beachhead‚ but it was just a small beachhead. As I mentioned earlier we had seven miles in depth and ten miles in shoreline. We could look on the slopes‚ up by the mountain when the smoke wasn’t on us. It wasn’t really a mountain. It was just a high ground. The Germans were up there. They kept smoke there so they couldn’t see us‚ so it might have been three miles. Maybe as much as four.

There wasn’t much battling in Anzio because there wasn’t any movement. It was all holding position. When the Germans moved out it was a matter of chasing them. I really think instead of being driven out‚ that they moved out. There was tank fighting because we picked up several tanks. I showed you some I think that we turned over. We picked up tanks that were knocked out‚ tanks that were burned‚ tanks that were mined. There was no battle that I know of like anything at all compared to Africa where a unit would move out and there’d be something decisive. It was all a holding action.

But they had learned not to send the tanks out against a German emplacement that was hidden‚ because that was suicide. So they either located the German tanks that were dug in behind a ridge and used a tank destroyer—a three–inch naval gun is what they had on ’em—or they’d use artillery or the air force. Call in fighter–bombers to plaster the German emplacement.

They had some difficulty with our airplanes. They had some errors. They had cases where the fighters went in on Allied troops. They worked out a system that was pretty foolproof where they had communication between the fighter planes and the ground observation. The fighter plane would come into position and ground troops would call for artillery. They’d throw a smoke shell in on the target and confirm with the pilot‚ you see such and such and he confirmed this. They would say “That’s the target! Go get ’em!” words to that effect‚ to keep them from strafing the Allied troops. This worked pretty well.

We kind of made a joke of the fact that they couldn’t hit anything with the bombs because you’d go to a bridge that was knocked out but there’d be a lot of craters around the bridge that had completely missed. Didn’t come close to hitting the bridge. But they dropped enough of them that they would eventually get what they were after.

This was early spring in the Mediterranean. It was warm in the daytime. It got chilly at night. There was a lot of stress at Anzio because the strategy which we didn’t know at the time‚ but the strategy was to… I don’t think it was to beat the Germans. It was to draw as many Germans down off the continent as they could because they were getting ready for crossing the channel. Of course we didn’t appreciate that. We didn’t even know it at the time.

The Germans were short on supplies. Far shorter than we were. They would have the crossroads pinpointed and say maybe at ten o’clock tonight they might throw a dozen rounds of artillery fire into our crossroad. They didn’t know if there were any vehicles there or not. They just threw a few rounds in and that was it. The next time they’d throw a few rounds somewhere else.

The Allies kept smoke. From the beach the terrain was rising and the Germans were on the high ground. The prevailing wind would take the smoke right up over the Germans. I don’t know where they got all the smoke generators‚ but‚ boy‚ they’d keep that smoke over the area all the time unless there was a storm. The Germans couldn’t see. I’m sure that was a blessing.

We had one guy there‚ a big tough guy from down in Kentucky‚ that was in a barroom brawl in every joint between here and Anzio. So you really couldn’t tell what metal a guy had you know till they go through it. They had to ship him out.

The guy I was telling you about that was always afraid. He left me stranded one day. I was moving a tank. You can’t see to park a tank. You can see to drive ahead‚ but you can’t see to go backwards. We were supposed to disperse the vehicles in that area and it was in a woods. Some artillery fire came in and he ran away. I had to get out and check the area‚ and get in and drive a little bit‚ and get out and check the area‚ and get in and drive a little bit to get the tank parked.

Then I went back to our bivouac area and found him in a dugout. “So where’d you go?” He said‚ “I wasn’t hangin’ around that. There was artillery fire.”

There was an artillery unit set up right close to us‚ within two or three hundred yards‚ with 105 Howitzers‚ and somebody said that you could see the projectile if you would stand right behind the gun. Another fellow and I walked over there one day when they were firing and sure enough you could do that. You stand right behind the gun and focus your eyes in the direction where the trajectory is going to be. When they fire‚ after a while you’ll see that projectile will materialize because it’s going straight away from you. That amazed me that you could do that. But it was true.

Let’s see if I can pick you out a picture here. We went out on collection points up there and the day of the breakout…you can see the mine detector there in the suitcase…and that was all Anzio. See the shrapnel marks on this tank? Just about where the crack is in that picture‚ there’s a mountain in the background there…I didn’t have a filter on the camera so it didn’t show up very well‚ but this high ground‚ the mountain‚ that was a German area. You can see a house that’s demolished in the background. You couldn’t walk on that terrain there without stepping in a shell hole. There was so much shrapnel on the ground we had to desensitize the mine detectors to get any reasonable reading on the thing.

Here’s a tank‚ you see the little back dot on the side? That’s a hole. Eighty-eight went through that. It didn’t burn. That tank didn’t burn.