saltboiler

times

A Journal of Jackson, Ohio, for Wildflowers, Local History, and Travel

ed clark—infantryman in europe with the 84th infantry division

ED CLARK

contents—click on a chapter

- 1—family and college

- 2—enlistment and basic training

- 3—army specialized training program

- 4—infantry training

- 5—winchester‚ england

- 6—first combat

- 7—life on the line

- 8—getting hit

- 9—crossing the roer

- 10—breakthrough

- 11—to the Elbe

- 12—after v–e day—army of occupation

- shove ha’penny—a video

- 13—after the war

- 14—q and a: reflections and conclusions

- “tried by fire”—a video

My dad in partnership with another fellow owned and operated a laundry and dry cleaning business. He died when I was eight years old and the business gradually went to pot. The laundry and dry cleaning business gradually went the way of home washers, and laundromats took over the old commercial laundries.

He was by the standards of the 1920’s a fairly prosperous man, a prosperous merchant. After his death, in the 1930’s the business just went steadily downhill till about 1940 when I graduated from high school. We were genteel poverty, I guess you would say. My mother was crippled in the accident that led to my father’s death, and she was unable to work. She was really confined to a wheelchair and two crutches. She could hobble around on two crutches, but both her legs were stiff, so she was unable to work. Our family just gradually dissipated its resources till about 1940.

My mother and I lived at home, and usually there was a companion there. Not really a paid companion, but there were two people I can remember. They lived with us and in return for their living quarters they helped my mom, did most of the cooking and most of the housework. I suppose that was a fairly common arrangement. They were older women, and my mother’s age, but they were physically able to get around so they did most of the cooking.

I had one brother, but my brother was 13 years older than I and he was out of the home, virtually, by that time. Married. Most of the time he lived away. Married in the country.

I joined the Army in my junior year of college. I had, unfortunately for him and fortunately for me, a cousin who was named Louis Kuntz. He was a toll collector on the Huntington–Chesapeake Bridge all his life, a bachelor, and we were about the only relatives he had. I can remember him. He’d come to our house sometimes for Sunday dinner. All he did all his life to my knowledge was work as a toll collector on that bridge. The only passion he had, every year he’d take a vacation and went to Mardi Gras and stay about two weeks. What the hell he did down there I have no idea, but apparently he enjoyed it because he went every year.

His connection with me is that he passed away in the late 1930’s and he left a sum of money for me for a college education. He left a sum to my mother which she desperately needed at the time. He also left me several thousand dollars, which was a princely sum in those times. With this and a small scholarship that I got, I was able to go to Miami University at Oxford. At the outbreak of Pearl Harbor that’s where I was.

I would have been in my sophomore or second year. I did go back briefly for my junior year before I entered service. I entered service in January 1943 as a volunteer through the draft. That meant my draft number wasn’t up, but realizing that I was going to be drafted eventually I volunteered at that time.

Those that signed up for the draft, unless you claimed an exemption or physically had an exemption, you were put in 1A. At the draft board you were given a number, a classification, 727 or something like that. Then by lot they drew those out in age classifications, taking what I suppose was considered a premium age first. Probably the best soldiers were nineteen to twenty–two or twenty–three years old and they were the first to go.

I was studying pre–law, with a major in history. I graduated actually after the war, but that’s a little further on. I graduated with a major in history and romance languages. I went there with the intention of taking a pre–law course.

World War II was much different, much different climate, much different time, much different attitudes of young people instead of like the Vietnam War or maybe even the Korean War. Most young people I knew, most were gung ho to get in the Army. They weren’t raring, but they were I don’t want to say resigned to it, but they felt that it was something that they must do. And should do, even.

People with 4–F’s—there were deferments in those times, there were mostly deferments in critical industries and/or agriculture and/or family hardship. If you were sole support of a family, sometimes you could get a deferment on that. Farmers could get a deferment. Skilled workers, if their companies would attest for the need for ’em, particularly if they were in critical defense industries were deferred. Student deferments per se were not.

What many college–age people did was to go in the so–called officer training programs right after college. They had classification V–6’s and V–2’s. I think V–6 was under the Navy program. You could go in to Navy, if you signed up for the Navy, but you stayed in college and took your basic training in an ROTC outfit. But it wasn’t a deferment from service to study. You were part of the Navy, but obviously the Army, the Navy and the Air Force was expanding greatly and they had need for officers. This was one way of getting officers, putting these ROTC units at the various universities. Now Miami had a Navy unit. Ohio State probably had all of ’em. A place like Otterbein might have had an Army unit. Or Ohio U. might have had an Air Force. But Miami had a Navy. I applied for that, but I couldn’t pass the physical for a naval officer.

That draft put me in what they call a 1–B category, which is supposed to be limited duty. You’re supposed to be a clerk or like this. It was ironic. I ran into a lot of 1–B’s. As the war progressed the 1–B’s became 1–A’s very quick.

I can recall a few people and none very close to me who were conscientious objectors. There were a few of those. I’m trying to think back now. A lot of ’em wound up in the medics, but I don’t know why. I don’t know whether there was any intent or that was an underground thing among them to go in the medical corps or whether the Army and the Navy shunted them to that, but there were a lot of ’em in the medics. But I don’t remember very many conscientious objectors.

Colleges and universities had a conspicuous lack of able–bodied men. The Army and Navy sports teams just ran rampant over everybody they played. Many small colleges gave up sports, because they didn’t have enough people. Most colleges and universities had—their salvation was the training that they did for the Army, Navy or Air Force, for the armed services, large contingents of these officer trainees or trainees in some sort of combat skills. That’s what kept a lot of colleges afloat together with doing research for the military for one type or another.

I went back to Miami in the fall of ’42, and what they had were overaged 4–F’s, kids too young to get in the Army. Seventeen–year olds who weren’t eligible for the draft. Seventeen–year olds could volunteer, training units, the V–6, the naval ROTC. They were big numbers, the Naval ROTC wouldn’t have fifty or seventy–five, there would be several hundred of ’em.

I went back to Miami in the fall of ’42 and stayed there a couple of months and then I came home and left school at the start of my junior year because I could see that I wasn’t going to be able to finish the year. That I would most certainly be drafted. So I came back home and spent several weeks at home before I signed up and went through the draft.

I signed my papers in January of 1943. My mother was regretful, sad, but resigned to it, because everybody was going. There was no thought of objecting to it. I never felt any community pressure, overtly, but 4–F was a scornful term. A very denigrating term. Also 4–F and people who got deferments were taunted because they’re not one of our boys over there. This was a...I guess you’d have to call it a popular war if there is such a thing as a popular war.

Prior to going we went to Columbus and I think it was what they call Fort Hayes there for a physical. That’s when I got this 1–B classification and secretly I was, I suppose, relieved, because I wanted to be a soldier, but I wasn’t damned sure I wanted to get out there in trenches and shoot somebody and carry on. So I thought, well, all right, this is better.

I came back and within a matter of almost ten days or something like that you were ordered to report. My first place I reported was induction at Fort Thomas, Kentucky, down by Cincinnati. I was there ten days maybe, ten days, two weeks at the induction center where they issue you clothing. Really there’s no training to it. You did some guard duty. I forgot what the hell we guarded, the mess hall I guess. Or something. You policed the area and that’s about all. Typical.

The recruits there were from the Ohio Valley and Indiana and down the River. I didn’t go with any particular close friends. I made friends with a boy there and we went through basic training together…a boy from down in the Portsmouth area named Ray Davis.

My wife always laughs. All through training and everything that went on, he said his goal in life was to be a motion picture projectionist. I don’t know why. That’s what he wanted to be. Motion pictures were a big deal at that time and you could see all the movies free. It was a good job and he said he didn’t like to get up in the morning. He said it would be good. He says, “All I ever want to do is get out of this man’s Army and go back and get on that N & W train and get off at Portsmouth and get on that overhead bridge there and look out there and see Navoo in the distance.” Whenever we go to Portsmouth, my wife gets so sick of hearing me, I say well, we ought to stop on this bridge and look for Navoo in the distance. See if I can see Ray over there, you know.

It was just one of those little things that strike in your mind. We were bedded down close together and we struck up a friendship in the induction center. We happened to go to the same place for basic training, which was a place called Camp Maxey, near Paris, Texas, which is up in the northeastern part of Texas, not too far from Texarkana.

It would have been in February. Funny climate. We rolled in there on a train and we could see these GI’s and everybody. We came in on Sunday, it seemed to me like a weekend or something. Anyway, they weren’t in drill. They were in off–time. They were lounging around in front of the barracks and everywhere getting suntans, some of ’ em in shorts. Maybe a volleyball game.

We got in there late in the afternoon and they just shoved us in a barracks. We didn’t get issued anything. It got so goddamned cold that night I thought we were going to freeze to death. A peculiarity of that area. I guess it gets hot in the daytime and cooler than hell at night. Anyway, that’s where we went, to Camp Maxey and the basic training was for, and I presume possibly because of my 1–B classification…this wasn’t infantry, this was a military police outfit.

Basic training in a military police outfit. Now the basic training in the Army in those days, whether you were a military policeman or a paratrooper or a finance officer, basic training was basic training. It’s about the same thing. But this was a military police training area. All of ’em there were presumably going to be military police of one kind or another. Now how I got assigned there I don’t know. What made the Army send me and Ray Davis to there, because we weren’t anything like military policemen. They had openings there at that time and here were some bodies and they sent ’ em, I presume.

A couple years afterwards, after lots of experiences in the Army, assignment to an infantry division overseas, combat, wounded, back, combat, I’m traveling. The war’s over and they gave everybody a three–day leave back to Paris. I’m riding in the back of a truck. It’s just a personnel carrier, and we came through there and it was on one of those big avenues, whether it was the Champs Elysses or something I don’t know.

We were stopped for traffic there and we were heading toward an R & R center in Paris and it’s a bunch of combat guys back from Germany and the war’s over. There’s this guy directing traffic. He was an M.P. There’s a buddy who was in basic training with me, a fellow named Kelley. So Christ, I stopped off and I said “Kelley, where in the hell you been?”

“Ah,” he says, “it’s been a long war. I finished basic training there, and went to New York and did some M.P. duty, then I went to London and did some M.P. duty there for a while, and now we’re here in Paris doing M.P. duty.”

I felt like punching him right in the damn nose because I left the M.P. thing for the great A.S.T.P. Program. I don’t know whether you know what that is. I’ll explain it to you. But here was this guy. If I had stayed there. Now it was my choice not to. That’s where I would have been. I would have spent my war years as an M.P. in New York, London, and Paris which would have been a hell of a lot more exhilarating experience than I went through.

Back to basic training. I don’t know what the Navy or the Air Force did, but the basic training in the Army was basic training no matter who was doing it. It was rifle training, marksmanship, military discipline, the classes on V.D., aircraft identification, that kind of stuff. No particular M.P. training. I don’t know what period of time. It runs in my mind we’re talking seven, eight, nine weeks, something like that. It was probably a little more abbreviated in war time than it is in peacetime basic training. I don’t know what that was.

There was no brutality in basic training. Our First Sergeant, I remember him well, was a man named Bonnamo and he was a robust, barrel–chested, almost movie typecast First Sergeant. East Coast somewhere, Sergeant Bonnamo, but he was more bluster than he was brutal. No, I don’t recall any brutality of any kind, not even any real humiliation, either mentally or anything else. It was a civilian army and pretty much everyone there was out of civilian life. There were a few old Army types around that they had in these training cadres, but all of us were really trying to learn how to be an Army, I think. Because, hell, they raised ten million people in an Army that was less than a million people, maybe less than that many. It expanded so rapidly that everybody was just kind of learning on the job.

You had officers, but the sergeants basically did it. You had some specialists coming in and then you’d go to the range and you’d have gunnery officers and gunnery sergeants that did it. The close order drill, lots of close–order drill. I don’t know why. I suppose it’s the British tradition or something in the army. You had to learn to march and do all the damned fancy maneuvers and almost like a drill team.

The sergeants may have been people that came in in ’40, ’41 when the draft first started. Or volunteers. There was a sprinkling of Army officers and reserve officers. In your Sergeant Majors and your higher officers, there were even World War I retreads still around, that were involved in the training process.

Really the only dangerous thing you did in basic training, and everybody feared it, was the so–called obstacle course where you had to crawl on your belly under the barbed wire and they pop up explosives around you. Then you had to scale a fence and work your way through a maze and then crawl under the barbed wire while they were firing bullets and they told you they were real bullets. Whether they were or not I don’t know. I didn’t reach my hand up to figure it out.

They kept your nose to the ground. They did mine. So I completed that and then I started in what they call the more specialized M.P. training. I started getting classes in Military Police discipline and handling of recalcitrant soldiers and what not. Police duty.

We were in a barracks. Parts of the base as I remember it were two story, and parts were one story, but they were all narrow dormitory beds lined up with a center aisle, beds lined up on either with your foot locker in front of your bed and that’s about it. And the washroom.

In basic training passes were very limited. I don’t remember whether you had to go through the first seven or eight weeks before you got a pass. I think that’s correct. I think you were confined to the base. Now after the training day there were PX’s and as I remember there was a movie. There was a PX where you could shoot pool, play cards. After that, if you were not on guard duty or kitchen police or something like that why you could get a weekend pass.

I don’t remember any unusual incidents about basic training. About the only people I can remember from basic training were this Davis and this Sergeant Bonnamo. I don’t even remember the officers because after about ten or eleven weeks, seven or eight weeks of the basic training and then several weeks, I don’t know how many went into the advanced training, I became aware of this A.S.T.P. Program. Many of us did.

This was named the Army Specialized Training Program. Anybody that scored high enough on the I.Q. test could apply for this program. The idea was they would pluck you from your units, retain the same rank. They would send you to college and give you a very intensive specialized eighteen–month course in engineering, language or occupation skills, military occupation skills.

As it was explained to us, the Army felt that…now you’re talking, you’re getting into ’43. The Army could see victory ahead. Somebody over in Washington or somewhere could see victory ahead. The world’s going to be pretty well devastated. We’re going to have to run it. We’re going to need people with language skills, lots of people in various countries. We’re going to need people, many, many people with engineering skills and many, many people with occupational administrative skills.

I was interested first in language skills because I’ve always been interested in language. So I applied for that. My second choice was the administrative occupation because I was in the M.P.’s. I thought, hell, I know a little bit about M.P. stuff in occupation. I was accepted in the program in the engineering division, of course. That was the Army. I was much more suited to the language course and I never had a goddamned bit of engineering training whatsoever, but they accepted me and I really don’t think they paid a hell of a lot of attention to any quality analysis of people. It was just where they needed bodies, the bodies would fit.

I was accepted to the engineering program and sent with about three or four hundred others from all over to Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. I don’t know whether you know anything about Lafayette or Easton. Easton is forty or fifty miles up the river from New York City and Lafayette, I’m sure you’ve heard of Lafayette. It’s an old, well–known smaller Ivy League school up there. I started in the engineering program, very intense. Right now you’re in differential calculus, organic chemistry. Never had any of this damn stuff.

College people taught these courses. There were one or two regular Army corporals, sergeants. There might have been one lieutenant there in charge of the detachment. But we lived in the dorms. Three or four hundred. We wore Army issue clothes, but for all intents and purposes we were college students. They did get you up early in the morning for your P.E. exercises. They did do that. You did have to sign in and out if you went to town or something like that, but it was very, very lax. No real military training at all. Once or twice we’d get in a column and we’d march somewhere and somebody comes in to give you a lecture on hygiene or the perils of sex, but very, very little, because it was supposed to be intensive work.

The people who dreamed up this program didn’t want your mind burdened with a lot of military stuff because they were shooting this other stuff at you. They were giving you a four–year college engineering college course or language or whatever. In this case it was engineering at Lafayette in eighteen months. They really threw it at you. Surprising to me, I did pretty well in it. I think probably spurred by the thoughts of them barracks back there in Texas and the sergeants and corporals and K.P. and what not. Here I am, hell, living a fancy eastern college and good food.

No real restrictions. You could go out in the evening. I think on weekdays there was a curfew time you’re supposed to sign back in the dormitory. You lived in dormitory rooms with two or three guys, just regular college rooms and you could go to town, eat where you like if you had the money. Go into Easton.

People treated you royally. You’re almost ashamed. You couldn’t buy a drink in a bar. If you took public transportation, a taxi or something like that, most of the time they wouldn’t charge you, just because you were in uniform. Hell, we weren’t really soldiers. We didn’t feel like soldiers, you know. We were up there. They had a regular college going on right along with us. There were many people there as I remember it. The enrollment must have been way down from what is normally. Colleges weren’t big in those days. Miami, now, is the smallest of the old land grant colleges and Miami must have sixteen, seventeen thousand. When I went to Miami they only had about twenty–five hundred students, three thousand. So colleges were smaller. Populations were smaller. I was up there three months and I went to New York City a couple times, went to Easton a number of times.

My rank was private. When I went in the Army my pay was thirty bucks a month. Gradual raises came along, but they weren’t much. I’d say less than fifty dollars. Now, I don’t remember what it was up there at Easton. That’s what I got, what a private got in the Army. Might have been forty dollars or forty–five dollars by the time we got up there. They kept pumping in a little raise now and then. Went to town often. No problem getting a date. I mean, there weren’t any young men. We were it.

I was there three months and then for some reason or other they transferred a whole bunch of us out of there to Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg. I don’t know why. I don’t whether I knew why at the time or I’ve forgotten, but some remained in Lafayette. Maybe they needed somebody down there at VPI. I don’t know. I went down there. Same deal, but a little more armyish down there.

They were cadets there. That was a military school, VPI. We used to get quite amused at ’em cause we were actually in the damn Army, but boy, these guys were spic and span. They’d march them cadets around, and “Yes, Sir!” and all that kind of stuff, you know, West Point stuff. We’d stand there laughing and making fun of ’em and they were kids to us. We were eighteen, nineteen, twenty years old and these were fifteen, sixteen year olds, seventeen year olds. Everyone that got through there came out an officer at that time particularly and we were privates and what not.

We’re down there, same circumstances, Blacksburg is just a backwater southern town, not much there. You had to go to Roanoke to get any entertainment or night life or bars or girls or anything else. About the only way you could get to Roanoke was on a train and I went to Roanoke once or twice but not often in six months. Lafayette was a lot better deal, everyone felt. Well, the ASTP program, I dont think it ever completely shut down, but now we’re nine months into it.

All of a sudden things started heating up over in Europe. The Italian campaign is started. They’re getting ready for the invasion. They’re going to need bodies. So, somebody somewhere decided that we got all these boys in these colleges all over the country. They’re all young, they’re full of piss and vinegar. It’s time to get them back in the fighting war. Now maybe, maybe they’d trained enough in the nine months. The long and short of it is… ASTP’s over. It was about April of ’44.

Now this was kind of a traumatic experience. Here we come, a bunch of us were sent to the 84th Infantry Division, which was stationed at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. The 84th Infantry Division was kind of a funny division. The 83rd and 84th were so–called sister divisions. They trained close together. I don’t know where the 83rd was, but it wasn’t far from there.

This was sort of an experimental program in the Army. Most of the guys in the 84th Division were older men, now I’m talking thirty through thirty–six, thirty–five. Most of the guys in the 83rd Division were pups. They were eighteen, nineteen year olds. The idea was they’d take these two divisions and train ’em side by side, do the same things with ’em and see who handled it better or whether you had to go slower for older people. Like I say, training an Army was a new thing for this country, and they’d never taken so big. Train in vast numbers. They didn’t know whether you should go slower on older men or whether you go faster or whether you had to have more psychological training for younger men or older men or what.

The 84th Division had been at its outset an experimental training division. But, as in most divisions in the states, they bled these divisions for replacements for casualties in Africa, Sicily and elsewhere, and in the Pacific. That’s why they reached into the ASTP to get the bodies to flesh out these divisions, because they were down to half strength, maybe. All right, here’s a division of old guys that’s been down in Louisiana training maybe for anywhere from a year and a half to maybe longer or maybe some of ’em six months. Anyway, old guys most of ’em in their early thirties, mid–thirties, some of ’em even in their forties that they had there. They’d been out in the god–damn swamps down there, eat up with chiggers and eating Army food and all the vicissitudes of Army life for older civilians. Here come this train load of college boys in. Who are these guys?

In comes this trainload of fresh young, young kids, all privates. These guys, most of ’ em that’s left are PFC’s or corporals or sergeants or staff sergeants or what not.

“Well, who are you guys” “Where you been?”

“Oh, well, we’re the ASTP boys. We’ve been in Princeton, been VPI, been Ohio State, been here and there and we’re comin’ in here.”

“Oh, you are?”

You can imagine what a trauma there was. We lived pretty hard because we’re going to show you college boys what the Army’s all about, see? I think they were a little fearful because here’s a bunch of young college–educated boys and they’re only a private and I’m a corporal or sergeant and hey, maybe he’s going to get promoted over me or something like that. Or he’s going to get my job. It took a little time to get together, so almost immediately we then went into maneuvers and advanced combat infantry training because they wanted to get these boys ready. What they were doing is getting the division ready for overseas.

The training consisted mostly of field maneuvers and war games. We went out in the damn swamps. We lived out in the field for weeks at a time and forced marches, setting up perimeter defense, digging holes, setting your kitchens up, simulating casualties so that the medics could practice. Everything. Practice war, practice river crossings, practice taking cover from approaching aircraft, unit combat infantry training. Much more intensive weapons training on, like, machine guns, mortars and BAR’s and other machinery of the infantry soldier at that time.

This is in April and May of ’ 44. April, May and June. About through the summer we went through this and I think it was either late August or early September they loaded us up and we went to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, which was an embarkation point for shipment to Europe and Africa. Here again I’m still thinking well, somebody over there will look at them records at Camp Kilmer and they’ll see that I’m 1–B and I’m not supposed to be a combat soldier. They won’t put me on that ship. They’ll take me off there and send me somewhere else to do something.

Most of these old guys in the 84th Division…it was started as an old division and they’d taken replacements out. Well, they took out the best, the best physical, and a lot of these old guys were the same classification I was, 1–B. For one reason or another they weren’t supposed to be combat. A lot of ’ em, a lot of us felt like there’s no way they’re going to send us overseas. We’ll get up here at Kilmer. Well, we never thought we’d leave Camp Maxey in the first place. We thought they’d leave us behind and just take the more physically qualified. So well, they put you on a damn train and send you to an embarkation port. You think well, they’ll stop us here. We’ll never get on that ship. Well, the whole goddamn division went on troop ships and we set out.

We’re supposed to land in France. For some reason we were supposed to land at Cherbourg, but an air attack or weather or something like that delayed us, we were diverted and they landed us at various points in England. The particular Liberty ship I was on landed at Southampton.

A Liberty ship is a small cargo vessel. We had some fairly rough weather on it. I have a pretty good stomach. I don’t get seasick. Many were. Terrible conditions. The holds in the ship may be this high. They might have four bunks up here just jam–packed in there. Puke, vomit all over the place. Many guys–I don’t suppose they ate over two or three times the whole trip over and I don’t remember what it took –– ten, twelve days maybe. Probably the whole regiment was on that ship. Probably fifteen hundred, two thousand people.

An infantry platoon had three squads. Now I was in what they called weapons platoon. Mortars and light machine guns were the two weapons that we had. It was sixty millimeter mortars and light machine guns. We had two mortar and three machine gun squads which made up the fourth or the weapons platoon. In each squad, mortar or machine gun, you had a squad leader, then you had the gunner that carried the gun. You had an assistant gunner who carried the plate, the base that you set the damn gun down on, and you had two ammunition bearers. Two or three ammunition bearers. I don’t know what the M.O. called for but some would have two and some would have three.

The two mortar squads had a mortar sergeant who would be a buck sergeant. Then there’d be a machine gun sergeant. Then there’d be the platoon sergeant who was over both squads—mortar and machine gun. Then he had two what they called runners that were messengers, supposedly.

An infantry platoon had three squads headed by a buck sergeant. I think there were ten men in each squad and a squad leader. He was a sergeant. Then you had a staff sergeant who was a platoon leader and he also had two runners. Then so you had one, two, three infantry squads. That would be roughly thirty people.

Of course, you had a platoon leader who was, supposedly he was a lieutenant. Now that worked back in the states. When you got over to combat usually you didn’t have that man included. They didn’t last very damn long. The platoon sergeant who was a tech sergeant would usually run the platoon. Usually, if you were in combat a few days you lost the platoon leaders. You didn’t have enough officers left. Officers fell quickly on the line. You’d be lucky to have your company commander and then the exec officer and maybe one other second lieutenant somewhere. The platoon sergeants generally ran it. Then of course you had your headquarters people, your company clerk, your company commander, your mess sergeant, cooks, supply sergeants.

There were three infantry platoons in a company. And a weapons platoon. Four platoons. Three rifle platoons and one weapons platoon. There were three rifle companies in a battalion and a weapons company. The battalion was organized somewhat similar to the company.

The weapons company in a battalion had heavier mortars, what they call an eighty–one millimeter, and they had the big fifty caliber machine guns. At the battalion level you also had what they call a G–2 officer, an intelligence officer and various other staff officers at the battalion level. Usually a major or a lieutenant colonel commanded a battalion. Companies were commanded by captains.

Here’s a roster of the 84th Infantry Division. That’ll tell us something, maybe. 334th Infantry Regiment. Okay, let’s see what they got here. Headquarters Company, 334th Infantry, so there was a Headquarters Company in the regiment. A service company is the next one. A cannon company. This is the regimental level. Now there’s a three rifle battalions in there that are in this. An anti–tank company. A medical detachment. Okay, I guess that’s it.

Then you go to your battalions which had a headquarters company and three line companies. There were three battalions in a regiment. Our regiment was the 334th. I was in Baker Company or B Company which was in the First Battalion, so it was one of the line companies in the First Battalion. The other two regiments in there of course were the 333rd and the 335th and they made up the 84th Division.

There are three regiments in a division. When you get to the division level now in combat situations many times you’d get units attached to you. We even had British companies attached under regimental command. You’d have a British tank company because most of our combat was done on the far northern flank of the American sector of the Allied lines, so we were flanked on the left almost entirely by British through most of our campaigns. So, many times there would be British companies assigned to us.

The British seemed to have, I don’t know whether it was just attrition, we always had, what do you call ’em, the mines–sappers that cleared mine fields, cleared a path through the mine field. They were almost always British. I don’t know whether they had particular expertise in that or it’s just a fact that we were bucked up against them. The British soldiers almost always did that kind of stuff. We had British tank companies assigned to us. We had British medics from time to time. You’d get what they call a combat force or something and you’d have a couple of regiments here and maybe a couple of British units and some air support or something. One guy would be in charge of the strike force, but anyway this was the organization of it.

Thirty–five hundred, four thousand maybe, people in a regiment. A full division had about fifteen thousand men in it. You had three regiments in a division, but to make up fifteen thousand, they have a lot of people at division headquarters. There was division artillery and there’d be division intelligence, division engineers, and that kind of stuff, so the regiments would make up maybe say thirty–five hundred. There you’re talking about ten thousand five hundred people. The other three thousand five hundred would be special staff.

Well, basically you’re foot soldiers but in the latter stages of the war, they found that the truck movements…they’d go around people. We were in Europe…there was a highly developed road network there, particularly after you got in Germany. Germany had good roads. The damned autobahn, they were the first superhighways in the world. We’d sail along that damned autobahn and you’d just go clear around pockets of resistance. Just leave ’em behind there and let ’em wither on the vine.

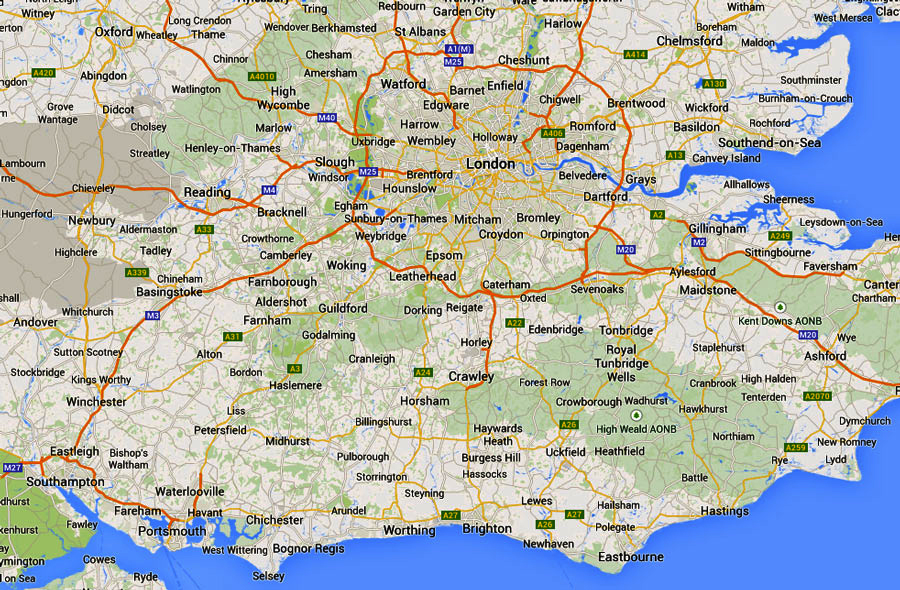

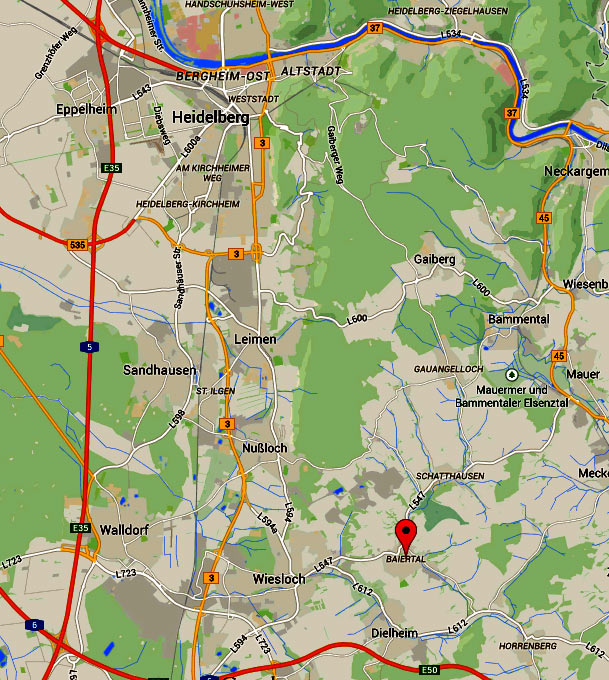

So we landed at Southampton. We were trucked, trucked or marched I don’t know which. I rather think trucked to a great little town called Winchester. I don’t know whether you ever been there or not. Lovely town. I just loved it. My battalion was garrisoned in the regular quarters of the so–called Winchester Royal Rifles. They had that all over a sign there. They were an old line British Army outfit which was serving somewhere and we used their quarters. We got there sometime in September. We were there about a month. Maybe not quite a month. Maybe five weeks, I’m not sure.

This was after D–Day. We went over as a division. I was in B Company, Weapons Platoon. I was an ammo bearer, carried ammunition for a mortar. I had to carry the damned ammunition. Well, everybody in mortar squad had to fire the mortar. If the gunner got shot, why somebody had to shoot the damned thing. But, basically, you carried the damn mortar shells. As many as you could carry. You just carried ’em in a damn sack attached to you.

A sixty millimeter mortar shell looked something about like this. I guess they weighed two or three pounds. Two fists together, about like a potato–shaped thing. Well, you’ve seen mortar shells. My memory’s hazy. Maybe that’s too big, I don’t know, but you could hold one of ’em in your hand easily, no problem. You had to because that’s the way you inserted the damned things.

You had your own pack on, I’d say you carried, damn, I’m not sure, I’m going to say you carried maybe twenty of them damn things and you might have carried forty, forty–five pounds of those with you. Yeah, plus whatever other gear you had. We had carbines, you had a sidearm. Now the rifle companies had the M–1’s, the old Garand. Weapons people had, well, after we got over there a lot of ’em just carried pistols. When you got up in combat you didn’t pay much attention to the Table of Organization. Then you did what you damned please, what felt better to you and what you felt took care of you better, but carbine was what you were supposed to carry. Ammo bearers. Now, the gunner carried, the squad leader carried pistols.

You only carried this load when you were in a combat situation. If you were on maneuvers or something like that, now. If you’re on a march or something like that, they’d put ’em in a goddamned truck. We didn’t have to carry ’em all the way over Europe. Just when we were going to go out and shoot the damn things. Now when we first went in combat I very quickly became a runner. I got out of goddamn carrying that damn load. The platoon lieutenant needed me and he made me a runner, which suited me just fine.

Back to Winchester. Winchester was pleasant. After we come off Louisiana, Camp Claiborne, hard training, summer training down there in them damn swamps, eat up with chiggers. It’s funny. Chiggers didn’t bother the old guys. I couldn’t understand that. They’d go out there and lay around that damn stuff and chiggers didn’t bother ’em and they’d just eat me up and all the other ASTP guys. We found out, after about a week or so out there, you got immune to the damn things. They wouldn’t bother you. Hell, they bite you. You get ’em. In my case and most cases you get over it. You just get used to it, I guess. Your system builds up its own immunity to ’em.

Most of the training we had was useful because it hardened you. It didn’t teach us about combat. No, no. No, I don’t think any training can. Combat was something totally alien to anything I’d ever experienced in my life.The training helped, but the training didn’t really prepare you for what you were getting into.

Yeah, that’s all. We just waited to get transported to France. We were in Winchester about a month, went down to the pub and played shove ha’penny and threw the darts, drank the beer, wandered around the town, dated the girls. Winchester’s a beautiful town. I just enjoyed it. I enjoyed it. This was Fall, and it was pleasant weather most of the time. I enjoyed the countryside and the little village.

We had a pretty good bit of freedom of movement. They just wanted to keep track of you. We didn’t do much training there. Hardly any at all. Calisthenics in the morning. They showed you a hell of a lot of films that you had to be there. You were pretty much in the barracks all day, except for weekends. In the evening you were pretty much on your own. You had guard duty or something like that. We always went almost every evening down at the pub. Then on weekends you stroll around, and you get so you can see like Winchester Cathedral.

You had to have a pass. You signed out. They weren’t too tough to get. I had one weekend pass in London. That was enjoyable. Went to Picadilly Circus. I got there on Saturday afternoon and I spent the night with a girl somewhere. In the morning, come back Sunday. A room somewhere. Picadilly Circus. Of course that’s where all the damn prostitutes were.

None of us had any idea of what the hell we were getting into over there other than just hearsay and what you would imagine and what you’d see in movies. We were there I think in the neighborhood of a month. I went one weekend to London, but we had a good bit of free time right in the Winchester area on foot. We had an opportunity to explore that town, which is a nice little town. I enjoyed that.

It was a kind of an exciting time, you have to say that. Of course for an infantry soldier it was an apprehensive time. It was for me and I think for most of us because it was fairly evident by then that the war in Europe at least was drawing toward its end. It was also very damned evident that we were going to get put right in the thick of the thing. I think there was a good bit of apprehension, but, as you say, it certainly was an exciting time. It was for me and I think for most people.

Of course, hell, for a kid from Ironton that had never been too much of anyplace, even going to England was an exciting time and seeing the damn white cliffs of Dover even from a troop ship or something like that was fun. You got a little taste of the English culture. As a billeted soldier in a small village you’re thrown in most with the other people in the company. About all the English we saw were the people you would meet in the pubs and maybe chance acquaintances you might meet on a weekend stroll through the village. So as far as getting really much of a taste of English culture, no we didn’t. We really didn’t have much chance to do that.

We landed somewhere in Normandy. I think it was Omaha Beach. Of course, Omaha Beach didn’t mean too much to me then. We got there probably late October or early November. Let me refresh my memory with this book here. It was in Normandy and it was before they had the so–called Patton breakthrough, or the breakthrough when they raced through France. There was still a fixed line or enclave that the British and Americans held, but you were still pocketed pretty well in Normandy there. If you remember after D–Day they were pretty well tied down to Normandy there for several weeks before there was a breakthrough.

We landed on a beachhead, I think, because I know we went off in some kind of a shallow draft landing craft and that took us up to the beach and you got out and you waded in water up around your ankles.

Then we stayed in Normandy, I don’t know how long. I’m going to say a week, week and a half, a couple of weeks. In that time there were a number of the men in the outfit were drawn off into what they called the Red Ball Express and a lot of our equipment was taken off because you were in this little pocket in Normandy here. The Third Army, Patton gets the credit for this thing, they broke out of this pocket and they raced across France in sort of a pincers movement. They bypassed Paris or there was no resistance in Paris, and once they broke out of this pocket in Normandy, there was some severe fighting in Normandy. You could see towns there that were heavily damaged, or you could see there had been a great deal of artillery and some pitched battles and heavy battles. The damn roads were depressed. There were high banks on the roads.

And these hedgerows. There were all these damn hedgerows that split up little individual farming plots and individual orchards and they were almost impenetrable. They were thick, because the French peasant, he’s a fiercely individual land proprietor and he put good fences around his home. Well, he didn’t put any fences. They put these hedgerows, and you could use those for pretty good cover, although our division did no fighting in Normandy. But we saw much evidence of it there.

When you had this breakthrough, what happened, the combat troops were far outdistancing their supply lines. I mean there was no provision for keeping up with ’em with gasoline, with ammunition, with various other things the Amy needs, so they set up sort of a, I guess you would call it a task force now, but they called it the Red Ball Express. From many individual outfits that were there in Normandy like we were, and we were encamped in Normandy. We were in tents and slept on the ground and just like a field maneuver or something. They took a lot of our trucks and a lot of our men to keep this drive going as long as it would go. They called this thing the Red Ball Express.

It was to supply these forward troops. It took most of our truck drivers and maybe other people there that had some truck experience and volunteers and by grabbin’ ’em out of their own mechanics and whatnot to keep this drive going. This drive went all the way from Normandy clear to France, clear to the Maginot Line. That’s what it did. This Red Ball Express was a makeshift deal to supply ’em. But that was only for a period of maybe, you know you’re talking a week and a half, a couple of weeks.

While this went on, while this breakthrough was going, we were still there in Normandy more or less in a reserve capacity or a waiting capacity because we had men gone, we had trucks gone. The big effort for the Army was to supply these forward divisions. They weren’t too much worried about here. They wanted to keep these guys going as far as they could go because they were liberating France. That’s what they were doing.

So we laid around in the fields there in France and, as everything seemed to be…now you, of course you realize most of my time over there in the ETO was from late October and early November through till VE–Day, so that was the winter months mostly. It seemed like it always rained. It seemed like you’re always in the god–damned mud. It seems like you’re always in a god–damned sugar beet field. I think all of northeastern Europe was a god–damned sugar beet field, it seemed to me like. We always wound up in a damned beet field. That’s what I say. Memory plays tricks on you. That’s the thing that sticks in my mind from that particular encampment anyway.

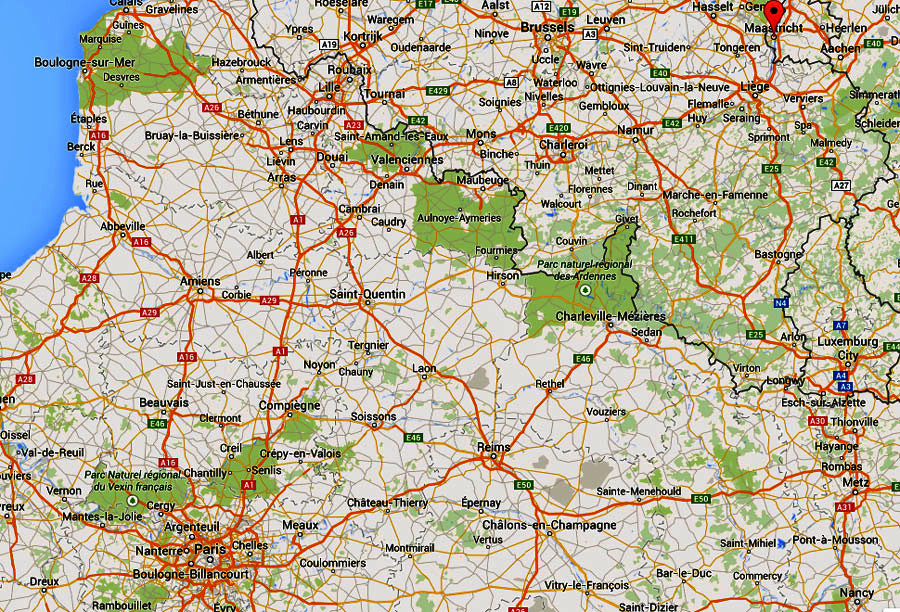

We’re there that period of time. Gradually Patton and the Third Army forward elements got across France, got France liberated, and run up against the Maginot Line and they stopped to consolidate. There were pockets to clear up, if you remember. If you’ve read any history, the Cherbourg Peninsula out there was a pocket of resistance. There was a bunch of pretty good German troops holed up in there. They were cut off, and it took a while to get those, to subjugate them. They stopped up there and our transportation troops came back. Finally, we moved across France in a truck convoy. This would have been the whole damn division. It was a rather uneventful trip. We went right through Paris. We didn’t stop. I think the convoy stopped in some environ or nearby area of Paris. We stopped and had a meal there and then went on.

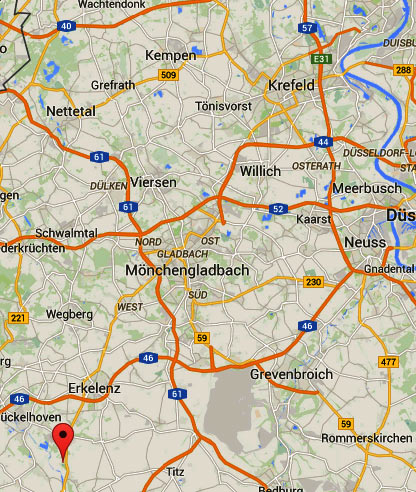

We went up to a very small part of Holland that had been retaken by the Allies. It was called the Maastrict Triangle because it was a triangular little enclave in there that was held and the major town in it was a town called Maastricht.

There was just a little triangle in there, just that little piece of Holland that was under Allied control. So that’s where we moved up into, close to that little town. As you see, we were pretty close. The British were all north of us here. The British were along the Channel, north. The American forces were here. We were part of the Ninth Army which was the closest to the British. We were assigned to the Ninth Army.

We got up to this Maastricht Triangle. Again we were encamped in a damn muddy–assed beet field. We were close enough to the lines then that you could hear the artillery. You could see planes flying overhead. You were cautioned—although we never had any, it just didn’t happen—we were cautioned that we might be strafed by German aircraft or German dive bombers. In the distance you could hear artillery, so we weren’t very far from the front line there.

The Allies pretty much had air superiority. Back then the jet plane was sort of a Buck Rogers type thing. We’d heard about ’em, mostly that the Germans had developed something called a jet which was much superior to any of the propeller planes and everything, and this might wrest air control back from the Allies. So we were always very apprehensive to seeing a jet. Once in a while you’d see one, whether it was Allied or German, I don’t know.

You would hear and you would see and feel and hear the damn robot things. The drone rockets. You would hear them going overhead and once in a while they would aim one at this part of the Allied encampment. But mostly those things were sent against England.

We arrived in Maastricht Triangle in November sometime. On the seventh we entrucked for a cold ride to Wittem, Holland. That’s arriving in the early morning hours of November 8th. Wittem was a small little village. We never got into Maastricht. I’ve never been to Maastricht. But it’s called the Maastricht Triangle because that was the large city. There was this little village near where we were encamped. This was really the first chance we’d ever see, the first chance we’d had to encounter any European civilians because there were civilians in this village.

We did go into the village and trade ’em food and knives and whatever because we didn’t have any damn Dutch money or any kind of money other than some American money people may have had on them. So we went into that village and got beer, maybe buy some potatoes or something to take back. One contrast to England and contrast to what little contact we’d had with us traveling through France—it wasn’t a very friendly populace. These were Dutchmen. I don’t know why they were suspicious or unfriendly to us, I don’t know, but we didn’t really feel any great wave of welcome from them.

That was also true for the Flemish part of Belgium which is German–speaking. Belgium as you probably know is divided into two major parts—a French–speaking part they call Walloons that speak French, and a Flemish part which speaks German. The Walloons were like the French. They were very friendly and open with you. The Flemish and the Dutch were not so. You felt uncomfortable around ’ em. I did and most people did.

So we’re there in this beet field and we went through some preparatory training things. Checked your armor, your supplies and everything. It was evident that we were going into the line, into combat because they were trying to make sure that everything was as ship–shape as it could be, that your gun worked and that you knew that the company had ammunition and whatever you needed for combat supplies.

We had individual weapons. We didn’t have rifles, we had carbines, but we had a sidearm. We had a sidearm, but once you got into combat that stuff didn’t go too much because nobody worried about what your rifle number was or whether you had a rifle or not. Most of the people in weapons platoons got rid of the carbines and picked up a German weapon. What they called a burp gun, a submachine gun which was a hell of a lot better weapon than a carbine. Carbine was all right, but it wasn’t very accurate at any distance and it didn’t have the thump of a rifle and you couldn’t put out the firepower with it. You could use a little damn German machine gun or submachine gun that you could spray with.

But now infantry riflemen, most of ’em kept their rifles. Of course the infantry had the automatic rifles. Each squad had what they called a BAR man, Browning Automatic Rifle, which was a longer heavier piece and fired automatically rather than firing from a clip. Bang, bang, bang, trigger pull each time. I wasn’t in a rifle platoon.

Each rifle squad would also have, maybe not each one but maybe one to a platoon, would have a bazooka man, carry a bazooka for anti–tank weapons or pillboxes or any kind of an emplacement where you could use that thing.

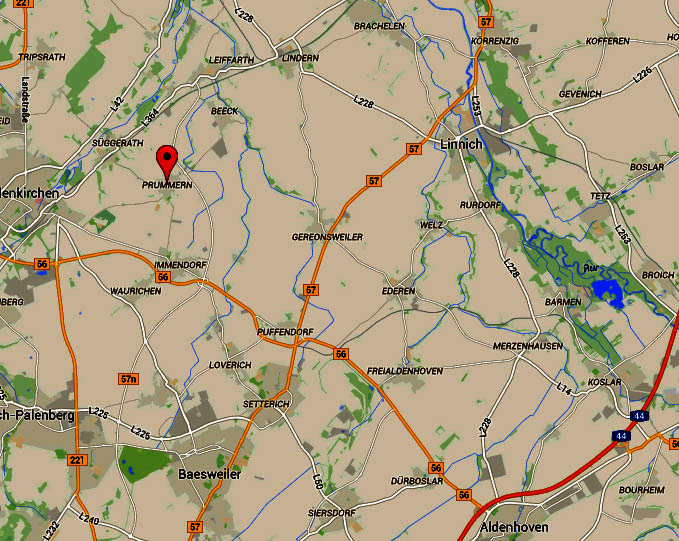

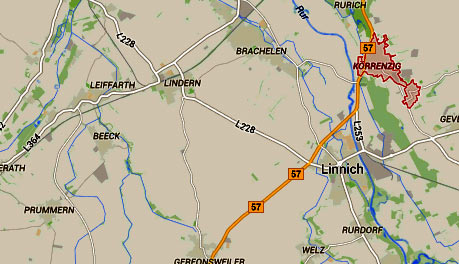

We move out to a place near the village of Prummern in Germany. As I remember it, we were in some kind of damn cave. I don’t know what it was, whether it was mine or a labyrinth or something else, but I remember very distinctly. It went way back in there. I can remember this is where we went at night. The company I was in, I don’t know how many people were in this damn cave, but I know our company was in there. This is where we stayed the night before we went into combat for the first time. It was kind of a spooky place to be for a twenty–year old kid, really. Here I am in this goddamned cave in some town in Germany. I have no idea where it is and it’s dark and lights and I hear all this damn bombardment and I was one scared kid, I’ll tell you. And most everyone was.

I didn’t really sleep very much. Fitfully, I suppose. I think up till then I felt (and I think a lot of people felt like me) that you could see this happening to you. Hell, you went to England, you went across, you went to France, you landed at Omaha Beach where all this fighting was. They took you up there. You knew you were going to war, but it never really hit you till that night. Now I thought how in the hell did I get in this place and what am I doing here? And am I ever going to get out of it? I think that’s the first full realization that, buddy, here you are just like the Roman legionnaires or Napoleon or somebody. You’re a goddamned infantryman, grunt, and you’re going to go out in this thing and your chances of getting chewed up are pretty good. Well, anyway, we’re in this cave so we move out the next morning.

At that time I had two or three special buddies. Let me tell you a little bit about our company commander. He was a fellow named Alcee Peters. In civilian life he managed a ten cent store somewhere in Louisiana or Mississippi, some southern state. He acted like a goddamn ten–cent store manager, maybe the worst type. I had a feeling he was sort of a petty tyrant. Nobody really thought much of him. But that son of a bitch was one of the best infantry officers I ever saw. He was good. He took care of his men. I’m talkin’ about through the sweep of it. He was intelligent. He tried not to needlessly endanger you, but he got the job done. He later became a major and a lieutenant colonel and later became battalion commander.

It fools you. A lot of the people that you go through training with and you think are going to be the real soldiers weren’t much good in combat. A lot of the people that you thought were fuck–ups turned out to be pretty damned good soldiers and people that you’d want to go to the wall with.

My platoon, outside of Peters I don’t remember much about other officers because officers came and went. In infantry companies we were fortunate enough that our company commander stayed with us, but lieutenants were a damn dime a dozen. They tended to get shot and wounded and things happened to ’em much more than anybody else because they were the ones that had to stick their head out and lead. We always felt, and I suppose it’s true at least it was a feeling, that if the Krauts could determine who was an officer, that’s the one they’d go for. The logical one to kill is the leader if you can.

Although I’ll make this commentary. I think what I feared most going into this thing, I suppose was what you’re conditioned to by reading stories about war, by growing up on wild west movies or seeing civil wars or something was hand–to–hand combat. Was small arms fire, you against this guy. Some guy shooting a gun at you here, and you firing and jumping around. Really, not too much of that did we encounter. Now maybe over in the Pacific Theater. Maybe in the Italian campaign they did. We had two or three times that we had to, in fact not long after we went into combat, that we had to clean out a village and there was a little bit of moving in with small arms fire against small arms fire. There was always the snipers. But as far as a guy that you could see or tell where he was shooting at you and you shooting back at him, not too much of that.

The horror of the war for us was the God–damned artillery because that was constantly with you. The mortars. The eighty–eight guns. The heavy guns and the shrapnel. That was where I would guess in my immediate experience that ninety percent of the casualties I saw where shrapnel casualties, not bullet wounds. More casualties in the ETO tended to be more of a long–range war than what I’ve read about the Pacific theater. If you talk to somebody there they may have had a completely different experience.

I never saw a bayonet fight. In fact a week or two after we entered combat I doubt if there was one person in fifty that had his bayonet. You threw ’em away. They were useless. They were just something extra to carry and stick around. If they kept it they kept it for an entrenching tool or something and most of ’em got rid of it and got hold of what they called a trench knife which was just a big hunting knife which you didn’t use to knife anybody. You used it to gouge out things. Or if your helmet got full of mud or something like that, you’d clean it out with it. It was a utensil.

Getting back to people, the platoon commander was a fella named Gould, Sergeant Gould. I think his name was Ira, something like that. Now he was from Pittsburgh. Long–legged, lanky guy. A good enough guy, but kind of a buffoon. Everybody sort of made fun of him in a way. He wasn’t a real leader or anything. I remember we were walking along the road one day and the people laughed. This was back in the states somewhere, we were on maneuvers down in Louisiana and we went by a field. There was a damn mule out in the field. He’s a city boy. He’s from Pittsburgh, see. He looked over there and he said “What the hell kind of a cow is that?” He was a dumbass! He was. After that, anytime we’d see anything we didn’t know what, we’d say “What the hell kind of a cow is that, Gould?” We’d ask him, you know. So that was sort of a byword in our platoon. He wasn’t much for us. He knew stuff by the book and he was always fair. Nobody disliked him. They just kind of laughed at him a little bit.

The mortar sergeant was really the leader of the platoon. He was a fellow named Simco, John Simco. He was also from western Pennsylvania as many of them in our battalion were. I don’t where. This may have just been an original contingent came from western Pennsylvania. He was from some steel mine town, close to Pittsburgh. He was a good noncom, a good leader. People respected him and he got the job done. Gould didn’t last very long after he got in combat. He got wounded in some fashion and went back.

Simco took over the platoon. He was the one that was the head of the platoon when we went through most of the combat. He was up for a battlefield commission the end of the war. Whether he ever got it or not, I don’t know. I’ve lost track of him.

The two guys probably I was the closest to in the company, one of ’em was a mortar sergeant named Jim Trentham. He was—as I told you I think before, the 84th was a division of older men originally. He was one of these original older men and he was from Monrovia, California. We sent Christmas cards back and forth for a long time, and then I lost him. He was sort of like a surrogate father figure to me. I respected him a lot. He was a wise old guy. He and his wife ran a restaurant out there near Monrovia, but he’d been with the 84th since the start. He was a damned good soldier. A lot of the younger guys in there looked up to him and went to him with their problems and he was understanding and a pretty good guy.

The two best friends probably of the same rank—one of ’em was a guy I still correspond with and I’ve seen him a couple times since the war and his name was Richard Hussey. He was from Old Town, Maine. I looked him up a couple years ago when we took a trip through New England and called him and went out and met him and his wife. He had a New England accent and he was a typical to my mind what I think of as a kid from down east.

The other one was a boy named Weldon Bergreen, funny–named kid. He was a Mormon kid from Salt Lake City. It’s funny. The big leavening that World War II did. I never knew anybody from Maine. I never knew anybody from Utah, but these were the two good buddies I had in the platoon.

Going into combat for the first time. The next morning we move out and we got a company of British—they call them sappers. They’re minesweepers and were attached to us. Now we’re up in the Siegfried Line. It’s late in the war and I don’t suppose these were like the blitzkrieg troops that the Germany Army had when they started the war. But they had an elaborate system of fortifications there and they were well manned. They certainly didn’t have the firepower that we had in artillery, but they had enough. As much as I needed or anybody else needed to go up against. They were dug in there and they realized, I think, that the Siegfried Line was their real last bastion of defense. If they couldn’t hold that, why, they were done.

It was the first taste we got of really heavy combat. So we move out, the first thing was I’d never heard such a fearful bombardment as they had preceding us to move out. The idea was to soften them up and then run ’em in there. Now under cover of this bombardment, we moved out. We had some British tanks and we went through minefields and these British sappers had been through there before and they’d marked out paths through the minefield. They marked ’em with little flags and banners and stuck ’em in the ground and you stayed between these goddamn sticks going up there.

Well, of course it didn’t take the Germans very long to see what was happening, to find these paths through the minefields. That’s where they put the goddamn artillery. Now the first bunches that got through, got through pretty good. Because the Germans were still under cover from this bombardment. The second or third companies though, by that time the Germans had found these minefields and they knew. As I say this is the Siegfried Line and they had predetermined co–ordinates. They knew where every goddamn inch of ground was there in relation to everything else. There wasn’t much guesswork with them.

If they could determine where this minefield was and find it on their map and they’re sitting back here, they could hit that goddamn place because this was their defensive line. This was where they’d trained and maneuvered and they had all this laid out in advance. Now, I’m sure they had the same problems that we were having on our side. In wartime things don’t work just like clockwork like you think it’s going to, like a computer. I mean you get new people in there and mistakes, you don’t do it right. We must have been the third or fourth company of our battalion through that damn minefield.

We were B Company. Baker Company. Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog were the universal communications terminology used for ’em in the military then. We were about the third or fourth company through there. It was pretty heavy going and tanks were going through with us. British tanks were going through there. We soon learned tanks were lovely creatures, but at least at that stage of the game, the further you stayed away from them goddamned tanks, the better off you were because they’d draw artillery fire and antitank fire just like honey to bees. It was nice to have the tanks if you run up against an emplacement or something, but you wanted to stay just as far away from them bastards as you could because the heavy fire was around them. We moved through the minefield.

It took an hour, hour and a half. Two hours, Three hours. I don’t know. Time is slow. You go a little bit, you crawl. There wasn’t no walking or anything.

After the damn artillery coming in you crawled. Now, if there’d be a little lull, you’d get up and run a few steps, but there wasn’t much lull. When you hear this damn stuff, then you hit your belly. If the artillery got hot, you took your knife and your shovel and whatever and while you’re on the ground try to scoop yourself a little ditch out. Or you’d get into a manhole where one of these shells had hit before and try to get below the plane of the ground a while until it let up for a little bit. When it let up, why you’d go on a little further.

Of course there’s people coming behind you all the time. So they push you out. I mean you couldn’t—I would have just loved it if I found a deep hole to get in that son of a bitch and just lay there for the rest of the time. Let someone else go on up there. But you couldn’t do that. There’s people coming behind you and “Hey, soldier, get the hell out of there! We’re in the war! This is Charlie Company coming through there and you’d better get up there.” Well, eventually we got through the minefield. Our objective was this little village of Prummern.

So the first thing I did in combat was go through a minefield. That was the first damn thing. Follow the path through this minefield. I was scared shitless, yeah. I just knew one of them goddamn things were going to blow up and then the goddamn artillery coming in and I didn’t know whether to shit or go blind. I probably did both, I don’t remember. But we went through.

I don’t think there was a damn minute I wasn’t scared. Most of the people the same way. Now you just can’t live in a outward sense of fear all the time. I mean you can’t go for days and weeks nervous and on edge. But I think there was always fear. As long as I was in that damned infantry company.

The first three or four days our company was decimated. It wasn’t twenty–five percent—it was about half gone. Half of ’em were casualties. Replacements were coming up because we took a pretty good thumping the first day. Now not everybody was killed, but casualties. Lost. I don’t know, some of ’em probably became prisoner. I don’t know. We never saw ’em again. Well, anyway, we got through the damn minefield and everything was confusion. That’s the big thing about war. Our particular company’s mission was to take some high ground around this village of Prummern.

Well, we started going to it, and another artillery bombardment come in. Me and Bergreen, that’s one of my boys, we got separated from the rest of the damn outfit. If you think that wasn’t a scary feeling. You see soldiers going here, you could feel the bombardment. It was, as all mornings then seemed to me, gray and wintry. There was a haze of smoke and crap from the battlefield.

You could see German prisoners straggling back toward the rear. You had no time to take prisoners. Many guys wouldn’t fool with taking prisoners. If they could get away with it, they’d just kill ’em, be done with it. If they came out with a “camerade” or something like that, you just waved ’em to the rear. You didn’t have time to guard ’em or fool with ’em or anything. Oh, maybe if you had a bunch of ’em and there was an officer around, he’d assign somebody to take ’em back to the rear and then come on back.

But anyway, for a period of time, Bergreen and I were lost from our unit. We didn’t know where the hell they were. There were pillboxes past this minefield. They were these big German pillboxes and they were dug into the ground and, with a concrete thing over ’em and trenches around ’em, fire trenches. So we got our ass in one of them pillboxes. We decided we were just going to stay there a little bit till this situation stabilized and we could see where something was because we didn’t know where the hell we was going—toward the German lines or our lines or where they were. So, I think the craziest thing that ever happened to me—I’m in this pillbox and Bergreen’s here and the trenches are maybe chest high around here.

We’re down there and we got our carbines and stuff and we’re lookin’ this direction and that, trying to see. All of a sudden somebody says something behind us. I nearly jump straight up in the air and so did he. There were about seven or eight goddamn Germans in this pillbox, see. Well, I could see, we’re out there talking and we’re looking around and and what were we going to do. You see one of them goddamn Krauts. Yell at me to shoot the hell out of ’em, these Krauts were behind us. He says something, and they come out, say “Comrade, surrender, surrender!” See, they wanted out of that damn thing. Well, they could have killed us both very easily. No problem. They had weapons. They were in the damn pillbox. We didn’t know. A pillbox didn’t mean nothing to us. I didn’t know what the hell was in there. I didn’t know where the opening was to it, even.

Anyway, we rousted ’em out of there and John Wayne’d ’em and everything. “All right, get over here.” Bergreen said “I’ll take ’em to the rear.” I said “No, you won’t. I’ll take ’em to the rear”. Well, anyway, he took ’em, see. And that’s the last I ever saw of that boy. Never saw him again. I don’t know what the hell happened to him. I don’t know what the hell happened to them prisoners. I don’t know what the hell, I stayed there and after a time, I saw a group of soldiers that I recognized as being from my company. I went over and joined ’em and I rejoined the outfit, but I don’t know what in hell happened to Bergreen.

Somebody told me he got hurt, that he was, he got hit on the way back. But he never came back to the company. To this day I don’t know what happened to him. I suppose he’s in that roster, and I suppose if I wrote to what they call the Railsplitters’ Society, which is the veterans’ group from the 84th Division, I could probably find out, but I never did find out.

We didn’t get very much further than where I was, around this pillbox area. I don’t think we got to the high ground that we were supposed to capture. We dug in there and of course you carried the rations. That night the Germans counterattacked and we pulled back some. That went on for a couple of days. We’d move out a little bit. You measured your gains in tens of yards really, through that Siegfried Line. We’d advance, take some ground, and at nightfall perhaps or the next morning the Germans would pinch you off and you’d pull out and move back.

The first damn thing you did was dig a foxhole. Or if you’re in a town or anything get in a cellar. That’s the number one priority is get under the ground. Because of the shrapnel flying overhead.

There were usually two in a foxhole, or one, seldom more. I don’t remember any night attacks like you’d think of Indian attacks at night or something like that, a wave of people coming at you. You’d get orders to move the hell out. You’d feel the pressure of the artillery. Maybe you would hear or see a German tank group coming, and you got the hell out of there. You were in an untenable position. Now when I say night attacks I’m talking about mostly early morning. Seldom attack at midnight or something like that because you couldn’t see what the hell you were doing.

It ebbed back and forth for a couple of days. Finally we were able to surround and take this village of Prummern which apparently was some strategic crossroads or something that they wanted. This was one of the few times that we did do some street fighting. It wasn’t fierce. Mostly pockets of resistance. Snipers. In a matter of a few hours the village was secure. We got run out of there and then came back again to it, I know at least once. I can remember going out of Prummern and coming back.

When I say a pocket of resistance, it might be one sniper or a group behind a wall or something like that. What you would do most cases is call for artillery fire. You would have a forward artillery observer there with you. If you couldn’t handle it with your own mortar squad or the battalion heavy mortar squad couldn’t handle it, then you called for artillery fire on it. That was the general thing, rather than charge it or something like that. Now if it’s an isolated sniper you would probably move on him. You’d call him to surrender. You’d give him a burst or two with the machine gun fire and usually you either killed the goddamned guy or he’d surrender. But if it was a fortified position with a group of men you’d try to handle it. Maybe your bazooka man if it was that kind of a thing, you’d call up your bazooka man and he’d fire a couple of bazooka rounds in there and that generally was the end of it. They would either surrender, withdraw, or if they were too strong for you to take, then you had to fall back. In most cases, the overpowering force was on our side.

You wanted to have tactical superiority and we did for the most part. Hell, if the German Army had equal weapons, I don’t think we could have ever dislodged ’em. The German Army, they were good soldiers. I don’t think we could have ever dislodged them if they’d have had equality in the air. They were a pretty beat up bunch when we got to ’em, anyway. When most American forces got to ’em in Europe. Now guys who were in the Italian campaign in Sicily will tell you a different story. Germans were still pretty good shape then. They had the whole fortress Europe. The big thing the Germans had, they were fighting a defensive battle. They were constantly shortening their lines and shortening their supply lines and falling back, where we were having to keep going forward more and more and getting more spread out.

A little bit about my frame of mind at this time. After four or five days of this, I’m watching and seeing what happened to my company and there was a constant stream of replacements coming up. Sometimes you’d never get to know the guy. You wouldn’t even know his name. He’d be gone. He’d come up and be gone while you were there.

I and most of the front liners here felt that it wasn’t a question of were you going to get hit. It was when you were going to get hit and how bad you were going to get hit. Were you going to get maimed or were you going to get a nice clean wound? Frankly, that’s what most of ’em hoped for, get a nice little wound in the hip or the shoulder or something like that where it would take you back to the zone of interior.

It seemed like to us there was such a tremendous reserve, particularly when you get a chance to go back to the rear for rest. It seemed to me like such a tremendous goddamn body of men, equipment, the big machine, and there were so few damn guys up there actually on the cutting edge of it and we were the guys on the cutting edge. It didn’t seem goddamned fair to me. There were so damn many guys back there in logistics and supplies and burial details and God only knows what, and just a few damn…It didn’t seem fair that I should have to go into battle and get pushed back then go back again, go back again. Why couldn’t I go up there once and go back and somebody else come up here and me go back there and push the damn paper, do that stuff?

There was a lot of resentment by the combat infantrymen to the so–called Z.I. or zone of interior guys. Unfair, because we would have done the same thing if we’d been in their place. But you couldn’t help but feel that way. You couldn’t help it. You were the guys taking all the shit and the misery. These guys were back there fooling with the ladies of the night in Liege and Paris and what not and doing jobs like that.

After a time, it was just dogged resignation to it. You see no way out. Here’d be Bill Martin and me right here, and there wasn’t any damn way I could go back, and Bill Martin go on. We both were there. It was just the luck of the damn draw that got you in the combat infantry. And you stayed with it. After it was all over, I wouldn’t have traded it for anything in the world.

That little blue combat infantry badge was really for a couple of years right after the war, that was the real status symbol in the Army, to have the combat infantry badge because anybody that was there knew that was the damn guy that was doing the work. By and large. There were other people that were in just as dangerous, submariners and fighter pilots and bomber pilots and whatnot there––they had their travails, too. I always kidded the guys in the Navy. I said, "Yeah, some of you probably were at just as much risk as a foot soldier in the Army but by God you had clean sheets at night, and you had your orange juice in the morning , even when you’re out at war. Where a combat infantryman’s life was a misery."

Everybody there was resigned. I mean, nobody there really felt buoyed about it and if they did they were nuts. They were screwballs that talked about the glory of war and how we were finishing off the Nazis and anything. Everybody there wanted out! Really.

But, by the same token, side by side with that, Bill, and I suppose it’s funny, you had a pride in your outfit. After a few days, and it didn’t take us long, we felt we were a goddamn pretty good lean, mean fighting machine. You were proud of the abilities you had––the martial abilities that you had to kill people, I guess. To take ground. Those things existed side by side.

You see stuff that just scared you deep down in your bones. I watched a boy named Nick LaBlanc who was a kid from a French–speaking family in New England. He spoke English, too, but he was French–speaking. A damn shell hit him out there. We were in foxholes, moving forward. We stopped. A shell hit him, heavy artillery barrage and he lay out there about half an hour and died. I knew the kid. We all knew him. Liked him. Screaming for help, but you couldn’t get to him. You couldn’t. Finally a medic came up and crawled out to him.

If there were ever a class of people who were to my notion the real heroes in the war it were the infantry front line medics because their job was to go to wounded people and help ’em. Even in the heaviest bombardment, they would go. And they’d get killed. That was their job and most of ’em did it. That’s the first thing you heard. People yelling for“Medic! Medic! Medic!” And they came. If there were one around, he’d try to get to you. Sometimes he couldn’t.