saltboiler

times

A Journal of Jackson, Ohio, for Wildflowers, Local History, and Travel

phil mills—naval seaman on the uss st. louis

PHIL MILLS

contents—click on a chapter

- 1—early life and boot training

- 2—shipboard organization‚ CRUISER ST. LOUIS

- 3—life on board THE CRUISER ST. lOUIS

- 4—japanese attack on pearl harbor

- 5—after pearl harbor‚ ON THE ST. LOUIS

- 6—on the shipley bay

- 7—after the war

- 8—q and a

My name is Phillip Eugene Mills‚ and I was born on April 14‚ 1923. I went to grade school in Indianpolis. I moved to Columbus when I was about twelve years old. My mother had died when I was seven‚ and my father remarried about five years later. I lived with my grandparents all of that time‚ in Indianapolis. When my father remarried I went to live with him in Columbus.

I attended West High School in Columbus‚ although I didn’t graduate. I quit school and joined the Navy. However‚ I did complete the G.E.D. in the Navy.

My favorite subject was manual arts. I ran track in school. Track was the only thing. My dad wouldn’t let me play football. I wanted to‚ but he wouldn’t let me. But I was pretty good in track. That is‚ the short runs. I was all right for a while‚ but then I would lose out on the long ones. But the dashes I usually done pretty good with that. I didn’t do too good with hurdles either. Back in my days I don’t think they had much javelin and disc throwing and all that other. Mostly just running.

I can vaguely remember the Depression. My father didn’t have a job‚ I don’t believe‚ but he had a shop in the back of the yard. An old chicken coop he’d fixed up. He was a dental equipment repairman‚ and he had been all his life‚ as far as I know. He had a shop back there‚ and he maintained a living through that.

I always think back about my childhood at my grandparents’. In fact every summer when I was living in Columbus‚ my brother and I went to Indianapolis to stay with my grandparents all summer long. It was an area that kids could roam. Really there wasn’t no harm to get in unless you fell out of a tree or something. We really had a good time.

I think they might have helped some‚ too‚ because my grandfather never was out of work. He was a railroader. He was a great man. I’m sure he kept my parents. He kept my aunt and an uncle of my grandmother’s. Then towards the end of it my aunt got married at a young age and he kept them. I don’t know how many families he kept. He always had money to do things like that because he was never out of work. His name was William Hershel. He was born in Ironton. I’ve been wanting to go down there sometime and see what I could find out. He’s my mother’s father.

I quit school in the tenth grade. I was seventeen. I quit school at Christmas vacation in ’40. Of course my father had to sign for me to join the Navy and he did‚ ’cause at the age of seventeen that’s the only way you can go in. I went in on what was called a minority cruise. I went in at seventeen and I know I had to stay till I was twenty–one. I didn’t have a full four–year enlistment‚ but then come the war and I had it extended anyway.

I went in to the recruiting office and then I was sworn in January the second of ’41. I was sworn in at Cincinnati‚ probably the post office. I think all recruiting stations at that time were in post offices. There was a recruiter in Columbus‚ but I guess back in those days all swearing in was done in Cincinnati.

We got on a train. I think we might have stayed overnight in Cincinnati. I’m not sure. I can’t remember‚ but I went to Great Lakes for boot camp. It’s up by Chicago. Outside of Chicago. Great Lakes‚ Illinois.

Great Lakes Training Center. I spent my beginning career there until probably sometime the latter part of March. We was given haircuts and clothes. Have you ever been in the service? I think they’re all the same in that respect. The only thing different between the Navy‚ the Army and maybe the Marines is the drilling. The Navy don’t have that stiff a drilling. But we did drill. We had companies and commanders. We were given our clothes and then we had inspections and we had to roll our clothes.

Now that’s a difference from the other services‚ because we had to roll clothes a certain specific way. We used clothes stops , cords with brass fittings on either end. They’re called clothes stops. We had to tie every bit of clothes perfectly‚ just right with a square knot in it. It had to be laid out just right‚ and there was an inspection. Seabag inspection is what it was called. We did it like that so that when you unrolled it‚ it was ready to put on‚ like it had been pressed. That’s how we kept our clothes in the Navy.

We lived in a building in an H shape. In the middle of that H was hallways with lavatories and shower rooms and washrooms and offices. On either end of the H was quarters at both ends‚ with a walkway in the middle. There was stanchions all around.

A stanchion is a big metal pipe about four inches or so. Steel pipe‚ bolted to the floor. They were situated in such a way that there was about four hammocks strung in each one. They were spaced around the whole room. The room must have been more then fifty feet long‚ each end of the H. This was all one level‚ fastened onto these stanchions.

After I went aboard ship‚ before the War‚ I slept in a bunk. Three–tier bunk. Everybody was issued a hammock‚ and when you get transferred you gotta carry it with your mattress. Rolled up just perfectly right and your seabag in the middle. It comes up around it‚ tied up‚ and then you can just put that on your shoulder and that’s your household effects‚ you might say.

In the older days all they did sleep in was hammocks. You always had your hammock. We had ’em in our bed. We had ’em folded and they was on top of the springs‚ with a mattress on top of that. That’s where they were. But our seabags were stored someplace else‚ because we did have lockers. Stainless steel lockers aboard ship.

The barracks on shore were wooden. They had some brick buildings‚ but I don’t believe the quarters were. The mess hall was brick. The barracks were all wood.

They assigned us companies. I was in Company 1 to start with. Right off hand I’d say there were about thirty men in a company. As time progressed‚ about two weeks or so‚ I came down with what was called cat fever. It was just the flu‚ I guess‚ and I was put in sick bay for two weeks. So I lost that number 1 company. Got put back‚ so I didn’t graduate with them. I graduated with another company.

That two weeks that I was in the sick bay‚ I was sick a week. The second week I was mess cookin’ for the ones that were sick. The others. So I wasn’t sick the whole two weeks.

We had involuntary drafting in 1940. That started in 1940. Some of the older men and some of the men without families‚ if they couldn’t be qualified for some reason or other‚ they didn’t have to go. There was people that got out of it. There was people that didn’t. I know some men that had to go. They were drafted into the Army. They never drafted into the Navy at that time. It wasn’t till after World War II that they started drafting into the Navy and the Marine Corps.

I had a feeling that we was going to get in a war‚ at that time when I went in. I really did have that feeling because of the drafting. At that age‚ I didn’t read all that stuff that was goin’ on‚ but I just thought‚ boys‚ there’s something goin’ on. That was another reason why I went in. Of course I knew Germany was fightin’ over there. Although I guess at that time we were losing some ships over there from German subs. Convoys‚ escorts and stuff. I don’t know what we were doing over there in England at that time‚ but that’s when we were taking supplies to them. We were helping them. That’s the only way we were into it.

Training. Seamanship. We had a seaman’s Bluejacket's Manual. Everything that consists with the Navy—tying knots‚ leggings. We had to wear leggings all the time. It was just that sort of thing. Studying of that type. And cleanup. Each company had a certain job to do. Either they was on guard duty or cleaning details. The company that I wound up with and finished up with had cleanup duty. We cleaned the administration building. That’s where I learned how to use a broom and a mop and a buffer. One of them round buffers.

We had some rifle training‚ but nothin’ much that I can remember that made any difference. Oh‚ we had to go through the manual of arms in our drill field and all that. We had to go through that stuff‚ but as far as tearin’ down a rifle‚ I can’t remember that we did anything like that.

I think the initial training at Great Lakes was about twelve weeks. I’ve been trying to think because my grandson is in Orlando Naval Recruit Training now. He’s coming home today after boot camp. But his was only about nine weeks. They’ve really shortened it up. I didn’t leave there until sometime the latter part of March. I had ten days’ leave out of boot camp‚ and then I came back and I was sent out to Mare Island Navy Yard to go aboard my first ship. It’s out at the San Francisco area.

It was a Navy Yard. A Navy base is just like an Army base. Back in those days the Navy had very few Navy bases. What they had was Navy Yards. And ships. I can’t recollect a Navy base back in those days. ’Cause even out in Honolulu‚ out in the Islands‚ the Navy had no Navy base. They had Navy Yards. But there was hospitals and that sort of stuff at Navy Yards‚ too. Fire departments and that sort of stuff. Some of ’em was operated by Navy people.

Whenever a ship went into San Francisco we just tied up at a dock which was run by civilians primarily‚ or we’d berth out in the Bay someplace. We stayed out there‚ made liberty on motor launches. But as far as Navy bases‚ prior to World War II‚ the Navy had very few that I can ever...I don’t know of any‚ really.

After I got aboard the ship I was on deck duty. I was a deck hand. The only training I got was how to swab a deck‚ wash down a bulkhead‚ wash down the overhead and all that sort of thing.

My rank was Seaman Second Class. I was a Seaman Third Class recruit in boot camp. You can’t get any lower unless you just don’t get in. After boot camp they gave me one step up to Seaman Second Class.

You got your own on–the–job training just from everyday—knots‚ seamanship‚ right and left‚ port and starboard‚ fore and aft‚ bulkheads‚ all that business. There’s a whole different language after you go into the Navy‚ I’ll tell you that. You don’t use the floor cause if you do you get called down about it. It’s a deck. That’s not a wall. That’s a bulkhead. And that’s not the ceiling. That’s an overhead. As I spoke about the stanchions. There’s stanchions all around the ship with rope on them. You don’t want to lean on that because they’ll get you for that‚ too. They’ll call you a farmer. There’s other names they call you I won’t go into.

This is March 1941 and I’ve had my ten days’ leave and I show up at Mare Island Navy Yard at Vallejo‚ California. The train pulled over to the Navy Yard and we got off with our seabags and marched to the ship and right up the ship‚ on the gangplank. Several of us recruits were in the charge of a sailor who had the orders for all of us.

-a.jpg) uss st louis (cl–49)

uss st louis (cl–49)

I went on board the St. Louis‚ a light cruiser‚ hull number CL–49. That’s Cruiser‚ Light–49. It’s the third size from a battleship. There’s heavy cruisers above a light cruiser and then battleships—back in those days. And destroyers and submarines. Those were the Navy’s men–of–war. So after I went aboard I stayed there for it must have been at least a month. We was in the Navy Yard for repairs‚ the ship was.

I think they had already been in drydock for a hull cleaning. The St. Louis was built in about ’38 on the East Coast. They continuously went to Navy yards for repairs of some sort. Hull cleaning‚ dry dock to clean everything off—barnacles. A ship gets a lot of barnacles.

The smallest gun on the St. Louis at that time was a .50 caliber deck gun. Machine guns. Then it was 5–inch and then our main battery was 6–inch‚ which refers to how big across the muzzle it is. Five–inch 38’s was the designation for the anti–aircraft guns. As far as the main battery‚ six–inch was all I ever knew. My division took care of the anti–aircraft guns. My division was the 4th Division. It handled the starboard side.

Our peacetime crew was about eight hundred That’s all there was before World War II. There were department officers‚ such as gunnery officer‚ engineering officer‚ first lieutenant‚ aviation officer. We had two seaplanes on the fantail. Those were observation planes. Some of the first cruisers‚ earlier‚ they had the seaplanes in the midship‚ but later on sometime they started puttin’ ’em on the fantail. Which means the rear of the ship.

There were nineteen divisions. From one through six was deck hands. They took care of the guns‚ topside and the living quarters. The seventh division was radar‚ which wasn’t a very big division. After that it went into alphabetical listings.

The A Division consisted of shipfitters. A shipfitter keeps the ship in repair. There was enginemen‚ machinist mates. They also kept charge of the lifeboats‚ boats and everything with motors in it.

B Division was boilers. There was machinist mates and water tenders. They took care of the boilers. There was different ratings in it‚ such as boilerman‚ machinist mate and boilerman‚ water tender. The water tenders saw that we had fresh water for the evaporators‚ fresh water for the steam engines.

C Division were communications. They were radiomen. They also had some yeomen with ’em‚ signalmen. Then the E Division was electricians. They took care of all the electrical equipment aboard ship‚ such as the man–powered telephones and lights and everything else that consists of electrical.

F Division was fire control. They had charge to control the guns‚ the main fire control. The automatic control of it‚ fire controlmen and radarmen.

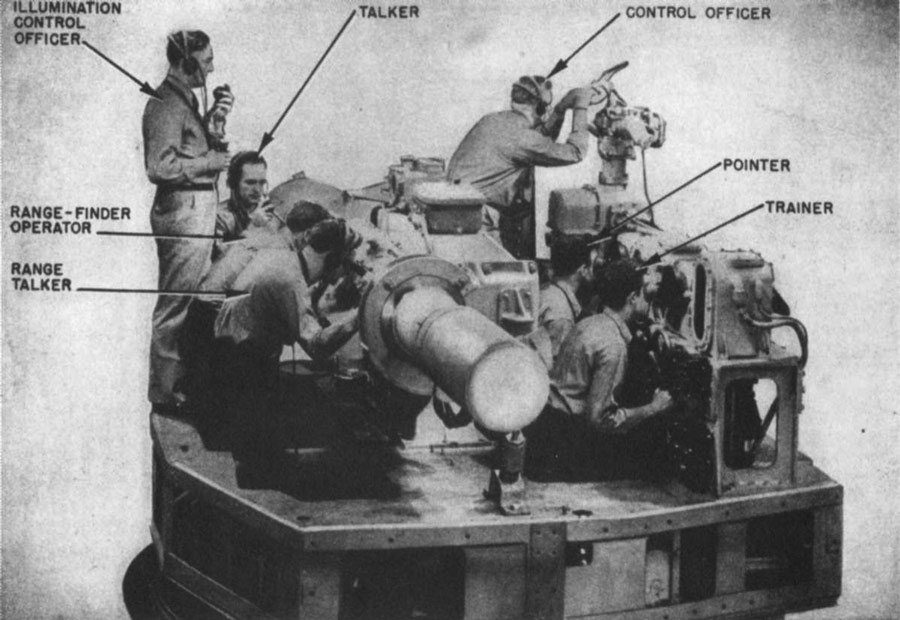

As a deckhand‚ we maintained and manned a 5–inch anti–aircraft director on the superstructure. We worked with a radarman. He was in with us. The rest of us was deckhands‚ but we worked closely with this radarman in the director. Pointing the guns was done by us‚ the deckhands. We had to point her and train her‚ and he was just a range finder. We had a range finder on there‚ and he operated that and told us how far away the object was‚ whatever it might be‚ with the rangefinder.

Most of the fire was anti–aircraft. Of course we could surface fire. We could see things on the surface if we needed to‚ which we did in nighttime. We did some of that‚ but primarily we was for anti–aircraft. The rangefinder could see a plane‚ but he couldn’t do anything unless that plane was flyin’ horizontal. Once it went into a dive he couldn’t keep up with it.

Later on we got radar‚ after the War started. We got radar aboard. Then we could pip. The pip was shown and you could track planes that was coming in‚ see how far away it was after you locked onto it.

After the F Division we got the H Division‚ which is pharmacist’s mate‚ the hospital‚ and along with that the Doctor. He was a departmental officer‚ too.

Then we have N Division. They worked with steel. They did their own work aboard ship‚ in other words. Most any ship in the Navy is self-sustaining. If they need a part fixed‚ generally they can do it–small part work‚ they can do it aboard ship. If anything big then they have to go to the Navy yard‚ and that was mainly the N Division‚ which was machinists mates.

The Marine Division was the Marines. Their duty was guard duty‚ the brig or whatever. They was also orderlies for the Captain of the ship. They stood outside the Captain’s office and his room all the time. There was one on duty all the time. The Marines guarding the Captain were called orderlies.

The M Division is the quartermaster. The quartermaster steered the ship.

R Division was also shipfitters. They were a little bit of everything. Damage control. They had divers also‚ and they even had boatswain’s mate. I really don’t know that much about the R Division other than the fact that they repair. Repair department‚ repair division.

The S Division was storekeepers. Ship’s cooks and bakers. There was also the barber was in that division. Back in those days in the S Division‚ there was a paymaster‚ too. They did the paying of the crew—paydays. The V Division was the aviation.

So that’s the nomenclature of the departments aboard ship.

The divisions were officered by a division officer and a departmental officer. The supply department had a supply officer. There was a gunnery officer‚ an engineering officer‚ and there was a navigator‚ and hospital‚ the chief hospital doctor. He was a departmental officer.

The First Lieutenant was in charge of the whole ship you might say. Damage control‚ lights‚ all these other divisions that I mentioned—the electricians and all that came under the First Lieutenant. He was a departmental officer.

The Captain held the rank of Captain on this kind of a ship. I think destroyers had Commanders‚ full Commanders‚ and sometimes they might have been Lieutenant Commanders. A Lieutenant Commander has a full stripe and a half-stripe. Commander has three full stripes. The commanding officer aboard a light cruiser was always a Captain.

Discipline was discipline back in those days. It was rigid. Somebody told you to do somethin’. It’s just like you jumped. I can tell you. That’s what it was in the Navy‚ back in those days anyway‚ in the war. You didn’t talk back. You didn’t question. The Army and everything else was the same way I think—especially the Marine Corps. That’s all changed. It ain’t the same way. When I talk to people‚ I’m anxious to talk to my grandson‚ see what he’s got to say‚ but I’ve heard stories. Younger guys that are retired and came out and joined an organization I belong to. They tell us how it is‚ and that’s how we know firsthand.

If you didn’t abide by discipline you got yourself in trouble. You got extra detail. If you persisted in your ways you went in the brig. They tried to give you a chance‚ but if you persisted in fighting ’em‚ you finally wound up in the brig. Eventually you was probably discharged‚ with a dishonorable discharge. That’s what happened to most of those kind of people. They couldn’t fit into the rigid regimentation.

Most of us were either seamen or boatswain’s mates. That’s all there was on the deck force. The chief boatswain’s mate of a division‚ he had charge of that division under a division officer. We had to muster every morning‚ the division officer told the chief what we had to do‚ what things that had to be gotten done. The chief told his other boatswain’s mates "Okay‚ this is what we gotta do." Right on down the line‚ down to the third–class boatswain’s mate‚ which actually wasn’t called a boatswain’s mate. He was called a coxswain‚ and he disbursed the duties out amongst the seamen. Such as‚ you’ve heard of “captain of the head”.

You never heard of captain of the head? A head is a latrine. There was certain crew where he’d tell certain guys "You go to the head and get it cleaned up." After the War started‚ I became leading seaman. I had charge of‚ maybe I had charge of a living quarters‚ and I had to see that the guys that was under me cleaned everything. That was done everyday—twice a day.

That’s why a ship is so clean. From morning‚ even before breakfast‚ up to lunch‚ after lunch till almost suppertime‚ all you did was clean the ship—the deckhands. That was either on the deck detail or in the quarters or the heads. Day after day. That’s all we did. The ship was clean as it could be.

Back in those days‚ before the War‚ each division had its own living quarters. The deck force‚ the deckhands cleaned all the living spaces‚ whether it was engineers or quartermasters or whatever‚ you did all that.

The ship is divided off into compartments. Every compartment is water tight. You can dog down the hatch coming down through it. And that compartment is water tight. If the ship was sunk that compartment‚ until it rusted away‚ would be no water in it. That would be a horrible death. I know some stories about it at Pearl Harbor. Below the main deck‚ practically the whole run of the ship was living quarters.

But they were small quarters. You take the port side and the starboard side of the ship. The compartment on the starboard side would be like the same compartment on the port side. Only there’d be a steel bulkhead in between ’em. With just a small aisle down the middle of ’em‚ with lockers on one side maybe‚ and the bunks on the other‚ with another row of bunks on the other side. You take ’em three high‚ you can get a lot of people in there. Lot of men‚ stacked three high.

After the war started‚ the complement was twelve hundred men. So then they had to make other arrangements. Then they went to sleeping in hammocks. In the mess hall and the other available spaces they could find to hang hooks‚ they welded steel hooks in there to hang a hammock from.

Out to sea‚ every day you got up at reveille and you swept down every compartment that you had charge of. Reveille was six o’clock‚ if I remember correctly. Breakfast was around eight. Then‚ if you were on the main deck itself‚ before breakfast we holystoned the wood deck.

The holystone consists of a sandstone brick with an indentation in it. Then you had a stick‚ like a swab stick. They would sprinkle sand all over the teakwood deck. Then they would wet it down. Then you’d go along with this holy stone and that stick and go back and forth‚ and you cleaned that deck with that holy stone and sand. To get the dirt from the tracks that people had made all day. That was done every day.

Before breakfast you always stoned the decks. I don’t know why they called it that. We rolled our pants up. We did this in bare feet. You didn’t do it with shoes on. You wanted to keep the deck from gettin’ dirt. And not ruining your shirt‚ your shoes‚ too‚ ’cause it was salt water put on there. This wasn’t fresh water. This was salt water that was put on there‚ on the sand.

My division‚ as I said‚ had the quarterdeck‚ and that consisted of everything in the middle of the ship. Now there was other divisions that did the fo’c’s’le‚ and there was other divisions that did the same thing on the fantail. There was two divisions on the quarterdeck. It was the 3rd Division and the 4th Division. The division that I was in was the 4th Division. We had the starboard side. The 3rd Division had the port side.

Whenever you were tied up in bay‚ tied up at a dock‚ the comings and goings from the ship was done from the quarterdeck. That’s where the Officer of the Day was. People came aboard or went off from the quarterdeck. We always came aboard or went off to the shore on a gangplank from the port side. When a ship goes in‚ she’s headin’ in. We’ve always tied up to the berth on the port side. But the day of the Pearl Harbor attack we were tied outboard of another ship‚ which made us the starboard side entranceway to the other ship. So‚ there is a difference sometimes‚ but it primarily was through the port side because of berthing.

Breakfast was in the mess hall. There were two mess halls‚ on the second deck down. I don’t remember where the kitchen was. Sometimes they were on the same deck. The bakeshop wasn’t‚ but dumbwaiters bring the stuff down.

Now every man on the deck force‚ back in those days‚ was a mess cook. He had to stand along the steam line and dish out the food and clean up the mess tables and the galley. Every man got that detail. I was doing that at the time of Pearl Harbor.

For breakfast we had hash‚ beans‚ potatoes‚ sausage‚ bacon‚ hotcakes. I don’t know if the Navy had dried eggs at that time. I think they were real eggs because I liked them. Back in those days dry eggs‚ I don’t think they’d been as good.

A ship could store a lot of food‚ and they had cold refrigeration places for food. We would supply up‚ back in those days before the War‚ for a certain amount of days ’cause we knew what we was going to do. We was going to stay out so long unless you was going to take a world cruise or somethin’. Of course you could stop along the way some place‚ like from San Francisco to Honolulu you could stock up some more supplies. As far as breakfasts go they was all good. They had a menu. You knew what they was going to have for breakfast every morning. There was a menu put out‚ and Saturday mornings was always big meals.

Pick up your tray‚ get your breakfast‚ sit down and eat it. They didn’t hurry you. I mean there was enough room you never had to hurry. I don’t know that any time I ever had to hurry. You could set there and smoke and drink another cup of coffee if you wanted to‚ and gab with your buddies. There was never any backlog. Well‚ there was always somebody in line until it got down to the end of the chow period. If you didn’t get there at a certain time (I’d say maybe 8:30)‚ the door was shut and the food was taken away and you didn’t eat.

You could wait till the eat–out stand opened up. That’s where you could buy candy. Incidentally‚ we called candy "pogey bait" and "gedunk" for ice cream‚ and of course they sold cigarettes and that sort of thing. But if you didn’t get your breakfast you didn’t get anything until noon.

Then you go back to the muster‚ every morning‚ and that’s when the orders are given out‚ after breakfast. Muster is just a line of men on the deck. Division officer standin’ there. It would take up most of the quarterdeck‚ and the quarterdeck was probably about fifty foot long on each side of the ship—port and starboard. So it would be full. After the War started—that’s when we had the twelve hundred complement.

The ship was something like maybe seven hundred or eight hundred feet long. Two and half football fields long‚ but not very wide. Not as wide as this house.

At one time when I still seaman second before I made seaman first‚ I had charge of the garbage detail. Me and another guy was in charge of the garbage grinder. The mess cooks brought their leftover food down to this garbage grinder and set their cans down there‚ and we’d dump it in this garbage grinder and start it up. I had charge of that for a while. And I was charged with a compartment. I never had anything to do with the top side because the boatswain’s mates were always up there‚ makin’ knots. They made knots. They taught to the deckhands up there. They taught ’em how to splice a rope‚ how to put canvas around a rope. It would be painted‚ and all that sort of thing—seamanship. One of the basic jobs of the boatswain’s mates was teaching seamanship to the men under ’em.

When I had the compartment we’d go down with maybe four or five men. Well‚ we’d already swept the floor—deck—down before breakfast. After breakfast we’d sweep it down again. Then we would start‚ get buckets of water‚ and we would clean the overhead‚ clean all the stanchions‚ all the little crevices and things you might find. We had white glove inspections from time to time‚ and I mean white gloves. If that officer went along and got any kind of dirt on his white gloves you had to do it over‚ got reprimanded. But that was done after breakfast until lunchtime.

Lunch was at noon. Lunch would consist of some kind of meat‚ vegetables‚ milk‚ coffee‚ whatever you want‚ whichever you want or you could have both. I always had coffee. We didn’t always have milk. Sometimes that was a luxury. Now I got to say that might have been powdered milk‚ back in those days even. I didn’t care for that milk too well. I didn’t drink too much of that milk back in those days. I drank coffee a lot. So‚ it might be lunch meat. Some days it’d be lunch meat‚ cold cuts‚ sandwiches of some sort‚ mustard‚ whatever‚ then a fruit of some sort. That was our lunches.

The fruit was canned fruit. Very seldom we’d get fresh fruit and that’s when we was in port for a while. I wouldn’t say it was fresh fruit. The only fresh fruit that I can think of that you’d ever get would be oranges and apples. I don’t think they could keep bananas aboard ship very long or they’d be spoiled, but apples and oranges they could keep.

And mashed potatoes‚ fried potatoes and sometimes would be for supper‚ gravy‚ sometimes steak or something. We had good meals aboard ship. We had good cooks and I never was dissatisfied with a meal that I can ever remember aboard ship. My grandson‚ to get off the subject‚ at boot camp‚ he was kind of a picky eater‚ and he’s told his mother. I’ve not talked to him cause he can’t‚ he’s limited in calls. But he’s told his mother. He says he likes the food. So that was a surprise.

Anyway‚ there wasn’t nothin’ wrong with the food. I guess the coffee wasn’t always that good sometimes. I don’t know. I’ve thrown it out from time to time—big mugs‚ about this tall. Them big thick mugs‚ I don’t know‚ is that what they had in the Army‚ too‚ china‚ heavy jobs.

If you’re in rough seas you don’t put up the tables. You set on the floor because the tables wouldn’t stay there. The benches would maybe collapse. And‚ if you didn’t hold onto your tray‚ you tray might go right across the floor—deck, if you’re in rough seas. Sometimes it was fun tryin’ to eat in those cases because you get in rough seas the ship will roll quite a bit.

If you’re between San Francisco and Honolulu‚ Hawaii‚ you hardly ever get into rough water. You go up into the Alaska area and over towards China‚ then you start gettin’ into rough seas. Up in the northern Atlantic it’s generally always rough. I was in the Pacific.

I was in some rough seas up in the Bering Strait in Alaska one time. This was during the War‚ and I almost fell overboard. There was wind and the ship was rolling and I was jerked out of the fire control director. I was lucky. One leg hit a guardrail and I flipped over and landed on the next deck down and was able to right myself and maintain my balance before I went over the side of the ship. You go over the side of a ship up there in Alaska in them waters up there and you don’t last long. It was dark‚ too. Nobody would have probably even known that I was gone till the next morning unless a buddy was tryin’ to look for me‚ and mention the fact that he couldn’t find me.

Supper was generally maybe five. We knocked off maybe four‚ and supper started maybe 5:30‚ between 5:30 and 6:00. But that was a daily routine‚ especially when you was at sea. There was a different routine in port‚ which all depended where you were. If you was in the Navy Yard it was a lot more cleanup because you might have fire detail, watchin’ a welder weld there so that he doesn’t catch somethin’ on fire. That’s what you did. Stood there with a fire extinguisher. In the Navy Yard you generally did a lot of chipping of paint‚ took off the paint. You started chipping paint‚ chippin’ off all the paint and puttin’ on new. That was your duty then.

There was never more than two coats of paint on any part of the ship. I suppose that all depends on how long it’s been since you went in the Navy Yard and how bad the paint is. Sometimes you might just clean it down because they never let a chip of paint stay there without bein’ painted. Bare metal was never left there; it always had to have paint of some kind on there. Maybe it was red lead. That was a red paint that was put on metal first before any paint was put on. Aboard ship on the top side you was always chippin’ paint in port. I never chipped so much paint in my life as I did during those days.

After dinner you didn’t do nothing. If you had compartment detail you did sweep down again and pick up any butts that somebody might have thrown on the floor. But they had cans‚ butt cans stationed all over‚ and a guy was supposed to use ’em. But you know how some people are. They still might put one out on the deck‚ and if you caught him you lambasted him. You didn’t let him get by with it‚ especially if you had charge of that compartment.

There was another detail. You’d be swabbing down the deck‚ and when the deck was wet‚ you didn’t let anybody come through. You kept everybody out till it dried. Now once in a while we had a situation where we’d have to‚ but we’d gripe about it. You might take a fireman from down below the deck and he’s gettin’ off duty‚ but he’s got to go to his bunk so he can go back to bed. Well‚ you have to let that guy through‚ and then you sweep up his tracks as he goes through. There’s some bitchin’ about it‚ but it was all more or less in fun.

We had movies all the time aboard the ship. Sometimes it might be in the mess hall. If the weather was nice we would have it on topside in the fantail. Other than that‚ recreation consisted of playing cards‚ talking‚ sitting around shootin’ the bull‚ darning socks‚ sewing on buttons. Washing your clothes or tidying up your locker.

There was a ship’s library. They had a lot of books in there. You could go down there and read until lights out which came about ten o’clock. At that time you had to turn in. If you wanted to talk to anybody after that and didn’t want to go to bed‚ you had to go some place where you wouldn’t be annoying somebody trying to go to sleep. Occasionally you might do it and you’d keep your voice low‚ in a corner someplace‚ but if you got a little bit too loud or something‚ somebody told you about it. Lot of times I went on topside. I’d go up on topside with my buddies and stand there and reminisce and say what we was going to do when we got older and when we got out or what we was going to do about our girlfriend in the last port. Then you’d just watch the horizon.

Sometimes you’d stand there. There was stanchions up on the fo’c’s’le especially‚ that you could set on those. If you didn’t‚ you didn’t have no place to set. You had to stand there on the side. If you was on the fo’c’s’le‚ though‚ and you was under way‚ the fo’c’sle moves up and down. If you could really watch it‚ it goes in an oval. A ship under way is not as straight as a car goes. It weaves like this‚ back and forth‚ goin’ through the water. It don’t go just like an arrow through the air. Then as a ship rolls back and forth and it’s goin’ up and down‚ that’s what causes the fo’c’s’le to waver in the front because it rolls over this way and the point of the ship will go this way and then it will come back this way.

Then if you’re on the fantail‚ there is a pretty picture. Flourescent. It’s a sparkle in the water you can see. You can see all these sparkles as the ship goes through ’cause there’s a lot of turbulence at the end of the stern of a ship when you’re traveling. Now the stern is pretty straight. I mean it don’t go back and forth because the whole ship is goin’ back and forth‚ rockin’ back and forth‚ fore and aft or side to side. But it goes pretty straight because it don’t have that same exact motion cause it’s wider back there.

Or you can watch the sunset‚ the moon shinin’ on the ocean. There’s a lot of pretty sights in that time of night.

When you are off duty you can go any place other than the engine rooms. Mainly it’s topside and your living quarters. You very seldom left your own area unless you had a shipmate that was in another division. Now‚ from the time I went aboard almost‚ I had four buddies. Each one of us was in a different division. I don’t know to this day how we ever contacted each other as buddies. We were like the Three Musketeers. We were the Four Musketeers. We made liberties together as much as we could unless we had duty.

We had a home away from home in Vallejo‚ California‚ with a welder. This is how it happened. Welders are civilians in a Navy Yard. They come aboard ship and do their welding and cutting and reconstruction of the ships. As I said‚ there was a fire watch‚ and you were standing there with the fire watch. You’re talkin’ to the welder‚ you’re gettin’ acquainted with him. I don’t know which one of us became acquainted with him first‚ cause we were all the same. We were seamen and had just come aboard.

The welder invited the fire watchman and any of his buddies to his house for a supper. A special meal‚ Sunday. So there was four of us that went to this one house. To get ahead of my story‚ there was one of us guys ... The welder had a daughter‚ and the daughter and my buddy became friends. Good friends. Girlfriend and boyfriend. He went with her all the time. After we got transferred and spread out and at different ports‚ he finally married that girl. He just died last year.

There’s three of us that we know of now. There’s one in Twin Falls‚ Idaho. There was this one in Dallas‚ Texas and myself. The one in Dallas‚ Texas‚ died last year. The one in Twin Falls is still living‚ and myself. The fourth man we’ve never been able to find. We’ve tried different ways. There was the four of us.

We would get up on topside‚ maybe a couple of us‚ and we didn’t have much of a past. We were all out of high school‚ practically. Oh‚ we might talk about somethin’ about back home. Like this one guy was from Tennessee someplace in the hills down there‚ and he would talk about some of that hill country stuff. The guy from Dallas‚ he never talked much about Dallas. The guy from Twin Falls‚ he talked about fishin’. As far as myself‚ I had nothing to talk about because I didn’t do nothing but go to school and play. I carried papers. We would talk mainly about the future.

I had been on this deck division for almost three years‚ and I didn’t want to be a boatswain’s mate. I didn’t want to strike for boatswain’s mate. I wouldn’t like bein’ a boatswain’s mate. They were not very well liked because they had so much authority. My views of it now are different‚ of course‚ but in those days I didn’t want to be a boatswain’s mate.

Shipboard duty before the war and after the war started was not much different. My battle station when I first went aboard was in this anti–aircraft director‚ and it was at Pearl Harbor. It was the same up until the time I transferred to another division to start striking for something I wanted to do‚ and that was yeoman. That was clerical‚ office work.

The gunners’ mates‚ all they did was handle the guns—two five-inch guns‚ and we had two on either side‚ one forward of the fo’c’sle or quarterdeck and one aft of the quarterdeck. My division had both of those two. The gunners’ mates‚ they took care of the ammunition and cleaned the guns. I guess every day‚ just like we cleaned the compartments twice a day‚ the gunners’ mates went through and cleaned the guns‚ make sure that they was all in workin’ order all the time. They did the same thing that we did day after day‚ only theirs was with the guns and ours was with the compartments and the decks.

My battle station was in this anti–aircraft director. I was on the lefthand side of that director. The director was not much bigger than this dinette room right here‚ and it swivelled‚ it went all the way around. It would go all the way round and round. As I said‚ I was on the lefthand side of it‚ down below. It was‚ oh‚ about as high as this room‚ I guess.

Up above‚ on the back side of it‚ was three stations up there. Once in a while I got to set up there. There was a gunner. There was the rangefinder. There was a pointer and trainer. The trainer had the wheels here. You’ve seen pictures of that. He turned these wheels with these knobs‚ two of ’em‚ and that thing would train around and around. It could be manual or it could be automatic. Then the pointer‚ he elevated the guns. All this could be done‚ controlled‚ from this director. We could control the guns. As we moved around when we were synchronized with the guns‚ the guns would move the same way as the director would. If the pointer raised his sights up‚ he was lookin’ at the target‚ and the rangefinder was tellin’ us ranges and directions‚ too.

Then we had the division officer. He had a porthole up in the top of the hatch‚ and he stood up there‚ and he had direct view of what was goin’ on. He’d say so many degrees to the right or to the left‚ come to so many degrees. As far as raising the guns‚ he could not sight anything there‚ other than when a gun shot and when it landed. Then he could say up or down or whatever.

I had nothing to do. I don’t know to this day what I was there for in that director. I had no function that I ever can remember to do anything. I never did a thing. I was just there. That goes into another detail‚ at Pearl Harbor December the 7th‚ during the attack‚ which I always remember.

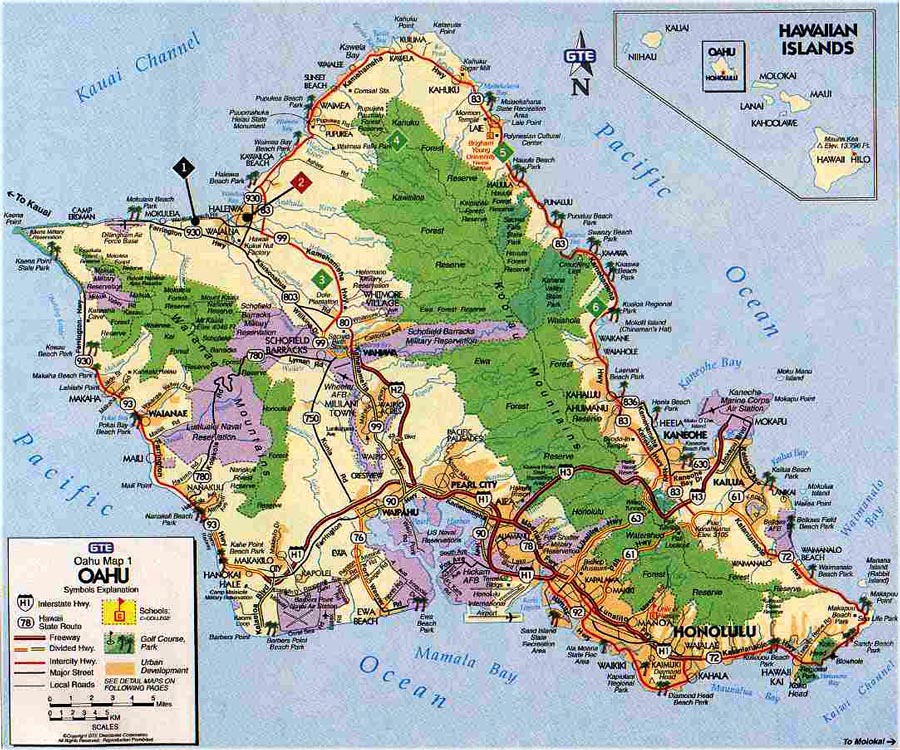

map of oahu‚ hawaii

map of oahu‚ hawaii

After we got out of the Navy Yard in April or May‚ 1941‚ we went to Pearl Harbor. When we went to Honolulu‚ we never came back to the States until sometime after the War started. We stayed out there operating on what they called training exercises. We would be ten days out‚ and ten days back in port. Then we might go in the Navy Yard there and do some kind of work or something. Whatever they had to do with the yard workers. When you’re in the yards like that you don’t have to have but two sections on at a time‚ so that would leave two sections for liberty. So maybe it would be every other day you’d get liberty.

That’s how the Navy operates. They never let everybody off at the same time. In some cases they only have to have one section stay on the ship. The other three can have liberty. Even though you got three sections off‚ you may not get liberty all three days. You might get liberty two days out of that‚ but that’s how they operate for liberty time.

When we were in a port like that‚ and you was the section that had to stay aboard‚ you just did normal cleanup and washing. Keep the ship clean‚ and that’s all you did. There might be some painting here and there‚ but the same thing that we did at sea we did in port. The only thing is it was curtailed a little bit because you didn’t have a full complement. As I said before the complement was about eight hundred men.

When we was in Honolulu for liberty we had to be back by midnight. We couldn’t stay over all night. The only people that could stay over all night was the people stationed there. Shipboard people had to be back unless you were an officer or something. Then you could stay all night.

There were quite a few ships at Pearl Harbor. There was a number of ships in there‚ about all the battle wagons we had. Why‚ I don’t know. I’m not sure whether there was some battle wagons outside‚ but the carriers were all out. The carriers didn’t come in. The Japanese were counting on them to be in.

I was sort of a loner. I had four buddies‚ but we didn’t always get to go ashore together‚ especially in Honolulu. And I didn’t drink. I didn’t smoke. When I’d go ashore‚ even in Honolulu‚ I’d walk around and go to movies. Get something to eat in a restaurant. Go the Y‚ watch ’em shoot pool‚ that sort of thing.

My liberty times‚ when I was by myself‚ in Honolulu especially I would say‚ those girls out there‚ especially the Hawaiian girls and the American civil service girls, would not have nothing to do with Navy. Unless they were stationed there‚ then they got to know somebody. But for shipboard people‚ none of us that I know of ever had a girlfriend. When you say girlfriend there’s other ways you know if you want to put the right name to it. Cathouses.

In fact I think there was a lot of civilian women out there that way. That’s what they went out there for. But as far as girlfriends‚ I had no girlfriends in Honolulu on my liberty time. They’d talk to you and all that. If you’d go in a restaurant some they talk to you‚ but as far as havin’ dates with any of ’em‚ I never had a date in Honolulu.

Now the people who were stationed out there‚ they would get acquainted with ’em a little bit. If you got acquainted with ’em‚ then you were all right‚ but you just couldn’t strike up an acquaintance on a short liberty anyway. That was one drawback in that respect. You didn’t have time to make any acquaintance. I suppose those girls knew that we was going to be goin’ out pretty soon‚ and they didn’t want to get attached to somebody like that. So that’s all.

The military had softball. I didn’t play any. There was some that I went to‚ close to Pearl Harbor. Nothing in Honolulu itself. They had movie houses and they had the YMCA‚ and at that time I don’t believe they had USO’s either. I don’t think they started until after the War started. You know USO’s? Well‚ they didn’t have any shows‚ but they had dances and they had girls that would come and you could dance. But you couldn’t leave with ’em. You could make a date sometimes‚ but you didn’t leave with ’em.

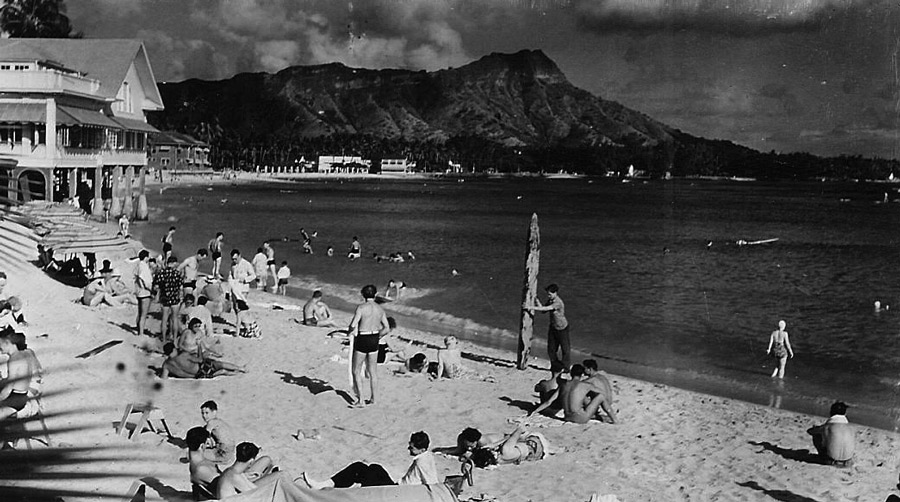

waikiki beach‚ hawaii

waikiki beach‚ hawaii

In Honolulu there wasn’t a lot of recreation. Just those guys that played softball. As far as the Navy was concerned‚ we weren’t allowed on the beach around the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. That was a big place at that time. That would be Waikiki Beach. That’s where everything is now. At that time there was only one hotel‚ and that was the Royal Hawaiian‚ and that was back down on Waikiki Beach‚ and it’s still there. You got to look for it. If you walk through a garden you can come to it all of a sudden. It’s still there‚ though‚ and I guess they use it. But that’s all there was there‚ and celebrities and everything used it. And I guess officers. When the war started it was used as a military hotel. But prior to the war it was an exclusive place.

They didn’t have any tours for military personnel. Frankly‚ Hawaii was not the tourist attraction as it is now.

Our objective in the ten–day training exercises was shootin’ the guns. Target practice‚ maneuvers, stayin’ on station‚ which was guard duty. Not much more than a hundred miles out‚ all the way around. During those days I didn’t know where we were after we was out at sea. When we left Pearl Harbor and got out in the channel and got outside of sight of the Islands‚ I was always workin’ below decks or something anyway. You couldn’t just stand around and gawk. . So I never knew where we were. Back in those days they didn’t tell you where you was goin’ or nothing like that. You just went. You was on the ship and the ship went and you were just there.

After the war started‚ then we knew in what general direction we were going to. They told us after we left. After we got out to sea they told us where we was going‚ what we might be doing.

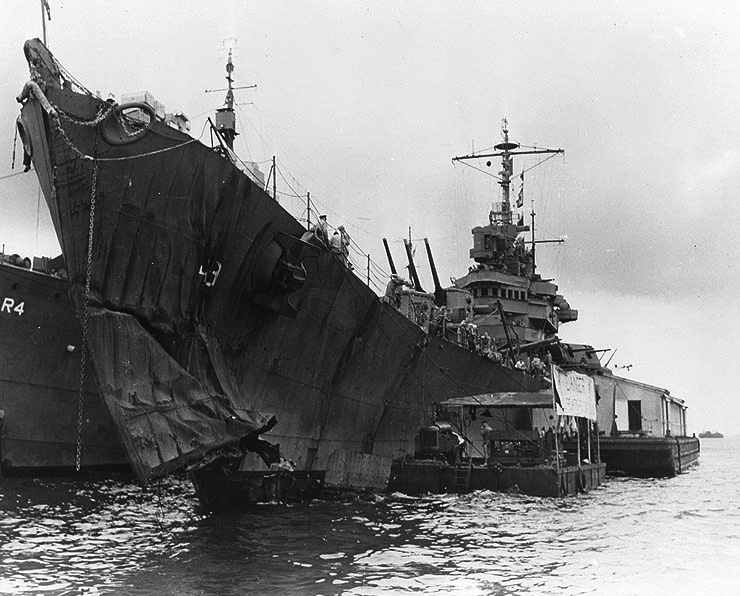

We came into Pearl Harbor the Saturday before the attack. We tied up in a berth alongside another ship which was the Honolulu‚ and it was tied on the dock. It was another light cruiser. She had a bomb dropped alongside the dock and hurt her from a dive bomber. So they couldn’t get underway because they didn’t know what the damages were to the hull.

On the other berth‚ on the port side of us‚ there was the San Francisco. Now that was a heavy cruiser. She was tied up on the other berth‚ and it’s a different size‚ it was a different structured ship. The Honolulu‚ the St. Louis‚ the Helena‚ the Phoenix —I can’t remember all of the light cruisers with square sterns. Before that a cruiser‚ whether it was heavy or light‚ did not have a square stern. They had sort of a round stern. The San Francisco was one of those. There was the San Francisco‚ the St. Louis and the Honolulu. We were the last berth before the mainland‚ so there was only three ships that I know of tied alongside there. We were just across the waters from the submarine base.

That’s Ford Island where the battleships were tied up. I saw the Oklahoma turn over. I saw the Arizona burning and we went by the Nevada after it was beached‚ ’cause it tried to get underway.

That Saturday I did not have liberty. I had to stay on the ship. If you didn’t have liberty you still could leave the ship, but you couldn’t leave the compound of the Navy Yard. You might want to go to the PX‚ that sort of thing‚ but you had to stay on the Navy Yard. You couldn’t go in town.

At that time I was mess cookin’. That’s what you say in the Army—KP. That’s what I was doin’ because everybody has to do it in the Navy‚ in the lower ranks. At that time I was only a Seaman Second. You had to be in there early to set up the food tray line. Get all the trays out‚ get ’em all stacked up. Get the food. It’ll come down in the dumb waiter and you take it out and put it on the steam racks. Get all the tables put up in the mess hall ’cause the tables were hung up to the overhead after every meal. The cooks probably was up maybe three or four o’clock in the morning. But as far as mess cooks‚ we didn’t have to do any preparation of the meals. We just had to set it up so they could come down the line and get their food. We would dish some things up‚ to ration it out‚ so that somebody didn’t take too much. We’d have to get the coffee cups out and everything for the preparation of the chow line except the cooking or the baking.

The attack on Sunday didn’t happen till eight o’clock. At that time‚ the breakfast was over‚ just about. We had started preparing to take up a lot of the tables and gettin’ prepared to scrub down the decks. All the liberty were back already on ship. They came back at midnight the night before. So everybody spends the day on ship.

I’m still in the mess hall‚ me and another guy (you pair up‚ you worked together as a team). These tables have metal rods and they collapse in the middle and come up‚ whip up underneath the table. Sort of a folding table‚ just the legs. I know that he and I had just reached down‚ and what you do is you grab the legs of the table and you lift it up and put it up in racks‚ a U-shaped rack up in the overhead. We had just gotten it up when General Quarters sounded. I remember all this to this day. He and I looked at each other‚ from one end of the table to the other‚ and I said to him‚ I said‚ "What in the world’s that for?" I said‚ "That wasn’t on the plan of the day."

Every day there’s a plan of the day put out. It tells you what’s going to happen during the day—every hour‚ anything special like drills. That was not on the plan of the day. That’s why I told him. I said "What’s that for?" "That wasn’t on the plan of the day."

The boatswain’s mate gave oral commands over a loudspeaker: "General quarters. Man your battle stations." That was the words they used. So you know where you go. You know where you are. You know how to go to get to your battle stations the fastest way. This is part of training.

As I got up to the after superstructure‚ where my battle station was‚ in that anti-aircraft director I told you about. The way I came up‚ I was running aft on the port side. The superstructure was on my right side as I was running aft. As I was running aft to get to my battle station which was another deck up‚ I saw a torpedo plane go past our fantail. To this day I don’t know why or how‚ but I recognized that plane as a Japanese plane‚ because of the red ball. I had not had much recognition drills or studying‚ but that red ball stuck in my mind. That was a Japanese plane. You could hear a lot of fifty caliber guns goin’ off. I got in my battle station‚ got up there and set down. As I said before I had no duties in that director.

anti–aircraft fire control director

anti–aircraft fire control director(cut–away view)

In the afterpart of that superstructure when you’re in port‚ the flag does not fly from the main mast. It is put up on the superstructure‚ and it’s a pretty big flag. It was floppin’ around. This director has a rangefinder that sticks out around‚ oh‚ probably nine feet or more across the front of this director. Well‚ the director officer had to swing it around and try to man the guns. They was having some trouble. I talked to him not too long ago about that very incident. They was havin’ trouble between the director and the guns. We couldn’t get coincided together. He had trouble swinging it around and all because this flag was flying in the rangefinder.

He told me‚"Mills‚ get out and take that flag down." So I got out. He turned the director around where I could get out. I took the flag down and rolled it up as best I could in my arms. I stood there and watched all the battle goin’ on. I saw the dive bombers come down. I saw the bomb drop between the Honolulu and the dock. I saw it comin’ down. I saw a Japanese torpedo plane burst in flames when he went over the hospital out to sea someplace. I saw our fifty caliber machine gunner on that afterdeck‚ the stern‚ that was fastened down on the deck. I saw him shootin’ that very plane with tracers. I could see the tracers goin’ into it. I would say to this day he’s the one that shot it down.

There was other people‚ other ships shootin’ at it‚ too‚ I think. I didn’t see their other tracers ’cause in a fifty caliber machine gun‚ especially the shipboard kind that I saw‚ there’s tracers in there which light up if they get fired. That’s how you guide on a target. Cause you can see that tracer bullet. I don’t know how many there are‚ maybe every five bullets is a tracer bullet. That’s how you can track your target. I know he was hittin’ it‚ and it burst into flames‚ but it was too late because the plane had already dropped his torpedo. I don’t know where his torpedo went. I didn’t see that. But all this was during the time I saw the Oklahoma turn over.

uss oklahoma capsized‚ other battleships burning behind

uss oklahoma capsized‚ other battleships burning behindThe airplanes were within a block of where I was. They was within a block of the fantail‚ but they was coming down across‚ right straight across our fantail. We could see the pilots. I don’t know how many there were. They wasn’t right after another because a torpedo plane would have to have vision in front of him. He’s got machine guns goin’‚ too‚ so when he’s goin’ down parallel with the ground‚ he don’t want another one of his friends up in front of him‚ shootin’ his wing guns. Before one would come down low enough to where he was parallel with the other one‚ he was rising up. The torpedo plane has to get down low before he drops his torpedo. You’d see them headed for the battleships.

I only remember seeing this one torpedo plane drop a torpedo‚ and he was headed directly for the battleships. The others that I saw go by I don’t know what they were doing. They were torpedo planes‚ but I didn’t see ’em drop anything because I was looking other places or doing other things. So I just saw that one drop a torpedo‚ and I don’t know what ship it went into. Battleship‚ that is‚ cause the torpedo planes were all targeted for the battleships. They wasn’t targeted for anything else. Because the direction they came in on that side of Oahu‚ that’s off over towards Honolulu. There’s a valley they came in‚ low over the island.

They had all kinda intelligence of where the battleships tied up‚ and sometimes there was carriers tied up there. But this time there wasn’t. Just about every battleship we had was in there that day. I’m sure that some of ’em had just came in Saturday the same as us‚ because the same fleet that we were operating with outside‚ we all came in the same day. Then at that time another fleet of ships went out‚ and they were gonna stay out ten days. I don’t know what they were‚ but I’m sure there was a battleship in that group‚ too. There was a battleship in all of ’em. In fact‚ when we got underway we met up with ’em. There was carriers. I don’t remember about any battleships‚ but I’m sure there was.

When I was standing there‚ I heard the fifty–caliber machine guns going off. It wasn’t all that loud. Fifty–caliber‚ unless you’re right on top of it‚ is not all that loud. Of course they’ve got some machine guns that you can handle by yourself‚ but the ones on ship are on a tripod anchored to the deck. There was a metal screw in the deck that was built in there. It was welded to the metal deck‚ and then the wood deck was around it.

I heard the explosions on the battleships. I saw the bomb comin’ down near the Honolulu‚ and I heard it go off. It wasn’t till later that I found out it went down between the dock and the Honolulu. I thought maybe it had hit it‚ because I did hear that explosion. I didn’t feel any explosion‚ though. We wouldn’t necessarily feel it because by it being tied up alongside us‚ we was outboard of it. I just heard the explosion after I lost sight of the bomb.

I saw the Oklahoma turn over. I saw the bottom of the hull. In peacetime the watertight doors weren’t dogged down. It just took on water on one side. It went over on the port side. Because that’s where it got hit, on the port side. That was the outboard side‚ and it was one of the ships on the outside of the fleet of battleships. Too much water on one side‚ and it just capsized right there in the bay.

I’m not sure I even had a watch. Time was of no instance. It just didn’t mean anything. I don’t know at what time we got under way even‚ in the middle of that. I do know that we got under way between a lull in the Japanese overhead bombers. The dive bombers had already came in before we got under way. The only thing that was going on at that time was the overhead bombers‚ the high-altitude bombers. The other low-strafing and dive bombers and torpedo planes was all finished when we got under way. So the time element I can’t tell you.

There was a lot of smoke‚ black smoke and all. There’s one picture that I would like to find. It’s a picture out of a newspaper‚ and it was called "Coming Through the Fire". It’s a picture of a Navy photo. It shows the St. Louis coming around the Arizona as it was burning‚ and there was a lot of smoke we had to come through. That’s why it says "Coming through the Fire". It shows us coming under way.

uss st. louis under way at pearl harbor

uss st. louis under way at pearl harbor

We got under way and got past that. The skipper did all this himself. Everybody aboard the ship had great pride in the captain because of how he maneuvered that ship. Ordinarily in a port‚ the captain releases his command of that ship to a pilot‚ and tugs come in at a certain point. Close in a tug would come in and have control of the ship‚ push it up alongside the berth. It’s not like a man you see in the TV with a little speed boat‚ who drives right up to the dock and that’s all there is to it. Those big ships‚ they didn’t do that. But the captain of the ship got under way‚ backed out of the berth where we were‚ out along past the submarine base‚ and headed out of base all by himself. This was without any tugboats because there wasn’t any available.

There’s been a story that was written up in a paper from Indianapolis‚ that my aunt and grandmother sent me. There was a radio operator on that net tender. After the war had started they interviewed him and he specified that the St. Louis was coming out of the channel‚ but the nets were closed. They weren’t going to open the nets because they was afraid of submarines comin’ in. The skipper flashed with the lights‚ you better open ’em cause we’re comin’ through. They opened ’em ’cause otherwise I don’t know what would have happened. We’d have probably tangled up in the nets‚ but he was gettin’ out of there ’cause we were going to meet up with the other fleet. I don’t think he had any idea what he was going to do once we got out.

As far as I was concerned‚ at my age of eighteen‚ my thoughts was why did we go out there? We’re safer in here. Because to me‚ the whole Japanese fleet was out there waitin’ for us. They could have taken Honolulu. They could have taken over the island of Oahu that day. They could have landed on Oahu and taken that island over for the first part of the war. We’d have really been in a bad fix if they’d have done that.

While I was standing there‚ I wasn’t afraid. I don’t know why not. Maybe I was too dumb. The only part I was afraid of as I said just a minute ago. I got scared when I found out we was goin’ out to sea. Basically‚ I didn’t know how to swim‚ and I didn’t want that ship sinking out there in the middle of the ocean someplace. To me‚ the Jap fleet could have been out there‚ waiting for anything.

There was two–men submarines out there. We had two or three torpedos shot at us‚ and we missed ’em all because they was on the lookout. We knew that those two–men submarines were around there at that time. In fact‚ we had one of ’em. They knew there was one of ’em came into the bay of Pearl Harbor. He came in when the nets were open when another ship was comin’ in. He came in underneath the ship.

How they knew it was in there cause I don’t know‚ but at that time we had those PT boats around there yet‚ and they was fairly new. They scooted around all over the Bay‚ trying to locate that two–man submarine. I don’t think they ever did find it. To this day I don’t know. It could be down in the bottom there someplace. I don’t think they dropped any depth charges. But we were tied up out in the bay at that time when that two–man submarine came in‚ and how they found out that was in there I don’t know. They mighta went back on out with another ship when it went out. We knew that those two–men submarines were around there. But at that time‚ even though we knew it‚ we couldn’t do nothin’ about it. We couldn’t drop a depth charge on ’em. Even if they’d surfaced you couldn’t have shot at it. They was just one of those things‚ in peacetime.

I did forget to mention one thing‚ and I don’t know why I forgot it. Three months before Pearl Harbor‚ my ship and my ship alone‚ the St. Louis‚ escorted an old Henderson troop ship to the Philippines with a boatload of Marines. All the way over there‚ probably two weeks at the most it took us‚ over and back‚ and all that whole two weeks there was full wartime watches. Darkened ship. Black‚ you couldn’t smoke on topside‚ you couldn’t go opening a door‚ hatch or anything outside with lights behind you. We were completely on a wartime basis‚ four on and four off. Most of us that I know of didn’t think nothin’ about it as far as the war picture. We couldn’t understand why we were doing it. They said our mail would be censored before it left the ship. We could not write home and tell anybody where we had been‚ what we had done. So that was a secret mission that we made to the Philippines with that troop ship. We were the only ship on it. There wasn’t any destroyer or nothing else with us.

It just so happened that one particular day we were on the way to Manila or coming back‚ they detected a submarine‚ and it surfaced. It was going in the opposite direction as us. It surfaced out a ways from us‚ and we had our guns trained on it. I’ve got to say and everybody else knows this‚ the government knew something was happening. I’m not saying they knew exactly where‚ but they knew‚ because I’ve brought out two things there. The fact that we went to a secret mission to the Philippines‚ and we knew those Japanese two–man submarines were around there. That was before the war.

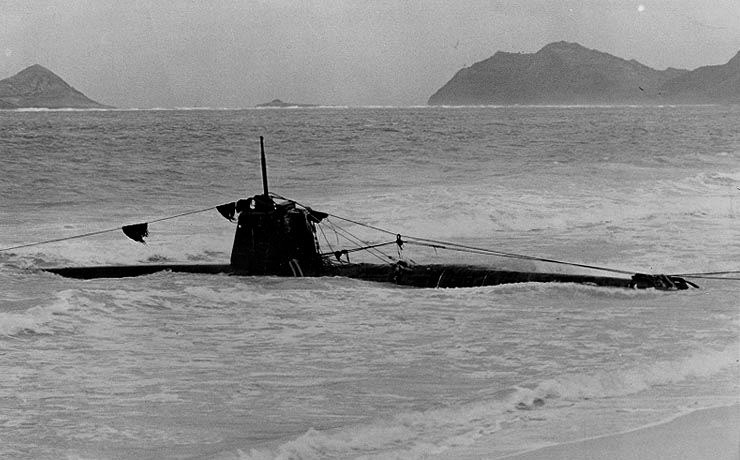

midget submarine beached at pearl harbor

midget submarine beached at pearl harbor

We fired on one submarine that was surfaced a little bit‚ and we got it through the conning tower. Now to this day the story was that the two–man submarine that they were bringing around through the country on war bond drives was the same two-man submarine that the St. Louis put a hole through the conning tower. It wasn’t that deep in there where it was. That was the purpose of those two–man submarines. They could go in shallower water. I’ve heard the story that he had beached himself on an atoll or something. We shot it. We shot him. Put a five–inch shell through his conning tower. If he had got off‚ he couldn’t go anyplace anyway because he couldn’t submerge with that hole through the conning tower.

I wrote to my division officer‚ and he wrote me back and he told me this story. He got called down for having me take the flag down‚ but he said‚ "I had to. I could not train my director." The main battery officer in another director for the main battery was a J.G.‚ and he was telling him to put the flag back up. The problem would be striking the colors. You don’t do that. But he really wasn’t striking any colors. He was trying to get ’em out of his way so he could do his job with the director. And that’s just what he told ’em. He says if you want to tell the captain‚ that’s up to you. But they never did.

The ship took no casualties at Pearl Harbor. As long as I was on it, for three years until I got transferred in ’43‚ as long as I was on it there was no one ever hurt‚ even though we had our bow blew off in a naval battle. When I say no one hurt‚ there was one man who got a purple heart because he was in the damage control party on topside in the forward fo’c’s’le on the main deck. A lot of the shell cases that had been ejected had fallen around the floor. That was another job of his‚ to keep them straightened out‚ so that they weren’t still scattered around on the deck. Well‚ when the torpedo hit and blew our bow off‚ the water came up over the fo’c’s’le and got one of them shell cases and dislocated his shoulder. He was up alongside the bulkhead. He got a purple heart‚ under fire. But that’s the only man in all the time I was on there that ever got it.

One of the reasons why we was able to get under way is we had just come in the day before. The boilers weren’t completely cold and they could get under way. We had steam boilers‚ and heated them with diesel fuel. Just like a furnace in your house‚ only it was bigger. Only thing is this is heatin’ steam. Steam turbines. We was able to get under way. They had to chop the mooring lines which is a hawser about six inches around. They had to chop them loose. The gangway‚ they cut it off with a blowtorch. I saw ’em doing that. Of course I was still up there holdin’ the flag when we was gettin’ under way.

After we started gettin’ under way‚ before we ever got out of there‚ there was a main battery in the superstructure. It had heavy anti–armor–piercing bulkheads. Those guys in there knew that I was out there. When we started to get under way they said‚ "You better come inside here and get under protection." So from that point on‚ I didn’t see much of what went except through a little slit that was in this part of the superstructure.

I saw one torpedo coming towards us‚ but I didn’t have anything to do with it. There was other people that was observing‚ and they radioed through intercom. We had hand–powered intercom aboard ship. It was a plate that rested on your chest‚ went around your neck‚ and you had earphones on. And then they had a speaker out here on this plate. I didn’t have anything like that on or nothing. I did in that director‚ I had those. That’s how the director operator talked to me when he told me to get out.

Our wake looked like a snake going through the water as we was going out because of those three torpedos that was shot at us. We missed ’em all‚ which was fortunate. We could have been damaged right there. That’s what happened to the Nevada. The Nevada was a battleship that did get under way. It was damaged and it was on fire when it got under way. Why they did it I don’t know.

It was in this paper‚ which is the U.S.S. St. Louis Hubble Bubble. This is a newspaper that we had aboard ship during the war and all. This is present day‚ but we’re using the same name. For about a year now I’ve got a computer and I’ve got 577 records of the crew of the St. Louis that we know about that are members of some sort. The ones that are dues are paid are active and the ones that don’t pay dues are inactive‚ but we keep all their names in there. Whenever we have a reunion—we’re going to have one in Sacramento next year—we’ll send everybody a newsletter‚ so that if they want to come to the reunion they can. But in there someplace is that story about that woman that saw that flag. Yeah‚ there it is‚ this article right here. "Rosemary Rawls‚ widow of Richard writes from St. Louis she went to Ohio for a wedding and while there visited the Air Force Museum at Dayton. Hanging above a sign ‘Japanese Surrenders’ is a rather tattered U.S. flag. It is framed. A sign reads ‘Flag flown on the U.S.S. St. Louis at Pearl Harbor on 12-07-41. It was later flown from the U.S.S. Iowa in Tokyo Bay at the time of the surrender in 1945.’"

After we got out‚ the skipper radioed to these other fleet ships out there for them to meet up with us. I don’t know how he did it‚ other than the fact that he was in Pearl Harbor during the attack‚ he knew more about what was going on‚ but he was taking command of the other fleet that was out there. He radioed to ’em to meet up with him. Where we met up I don’t know‚ but there was some carriers‚ the Phoenix was out there‚ I believe and a lot of destroyers‚ other cruisers‚ light cruisers‚ heavy cruisers.

We started searching for the Jap fleet‚ but the Jap fleet was long gone. We never did find it. We stayed out three days‚ and all during that three days we were on battle stations. We did not leave our battle stations for the whole three days until we came into Pearl Harbor again. We were issued impregnated clothing for fire‚ you know‚ for fire code. We had to keep that stuff on all the time. The battle station I was on‚ we couldn’t leave because it was anti–aircraft. Mess cooks and cooks would bring around to every battle station cold ham sandwiches and coffee‚ and that’s what we ate for those three days. For the first time in my life I had the jock itch from that impregnated clothing‚ cause there’s no air. It don’t breathe. Up there without a shower or nothin’ else for three days‚ I got the jock itch. I’d just take Aqua Velva shaving lotion which was fifty percent alcohol and just rub myself raw with it. It hurt, but I got rid of the jock itch.

I slept right under the steel deck‚ right there around my battle station. Some of us would be awake as required. I had no real battle station duty on there‚ so I just slept on the steel deck outside. If anything happened I just jumped in. That thing had no protection from machine guns or anything. It was paper thin. Very thin sheets of steel. Tin‚ more or less. So if those dive bombers had made their strike‚ why they didn’t I don’t know to this day. They did not try to drop any bombs on us‚ but there was a string of planes coming down. I could see ’em coming down‚ and then peel off and then banking up. If they’d have dropped a bomb any place close to that director‚ it would have just knocked that director right out. Or even with their fifty caliber they could have killed just about everybody in there with their machine guns.

If the Japanese had lined up their planes right they would have hit something. They’d have hit something more than between the dock and the ships. The could have done more damage. They could have done almost the same damage as they did to the battleships‚ with those dive bombers. Then‚ as I said before‚ they brought in horizontal bombers after these other things had come in‚ the torpedo planes and dive bombers. You could see the horizontal bombers going over. They probably did some damage on the Ford Island runways and things‚ hangars. There was damage done over there‚ too.

They was flying over straight‚ just dropping bombs. As I said before‚ the Japanese weren’t very efficient. They got more efficient‚ but that attack on December the 7th‚ they were very inefficient. They could have done more damage. They could have taken over that island Oahu. If they had taken over the island of Oahu‚ they could have been making attacks on San Francisco and all the California coast.

Anyway‚ we were out three days and never saw the enemy. We returned to Pearl. It was still a mess. Just sunken ships. There wasn’t no fire. It was just turmoil as far as I could see. I don’t remember all that much‚ other than the fact that you could see the damage done to the battleships. We couldn’t see Ford Island. We couldn’t see the damage to the hangars and all. The only damage we could see was to the battleships.

I don’t remember where we tied up when we came in. We started loading up more ammunition. I’m almost sure that for the first time we got radar. We didn’t have radar. They put radar screens on top of our superstructure. We got radar on that anti-aircraft director‚ where we could see a pip and track a target with it.

At the same time we got new complement. We got complement from all these damaged battleships. I don’t know where they all come from. I got a good buddy in Columbus that was on the Nevada. He came to the St. Louis‚ and there’s a few others that came from different ships. We must have gotten the biggest part of our crew from the Nevada. I don’t remember anybody else that came from another battleship.

I belong to the Pearl Harbor Survivors’ Association‚ and I go to a lot of these conventions. I talk to a lot of guys from different ships. I talked to a guy that was cut out of the Oklahoma bottom. Some guys were cut out of that ’cause they was trapped in the hull of the ship. I just heard a story in Toledo here last month of a guy that was very close to where they first cut into that thing. There was a little explosion and he got killed—after all that.

We got most of our crew from the Nevada‚ our additional complement. I’m sure we got some recruits from boot camp. In those three days they were scurrying around getting people from everywhere. Every ship in the Navy that was operable got additional complement. From eight hundred to twelve hundred. That was what our wartime complement was. The reason is you got more battle stations and you got more things to take care of. It just takes more to operate it‚ I guess‚ in wartime. So we got an additional complement to a toal of twelve hundred men at that time.

At that time we went out and met with another group of ships. We made the first strike against the Japanese on the Kwajalein Islands‚ south of Hawaii. The Kwajalein Islands. We made our first bombardment. We made the first attack onto the Japanese. The fleet went down to the island. We went in a line‚ throwing our shells onto the beach. Even in those days we knew what the Japs had on certain islands. This kind of stuff goes on back in the peacetime‚ even as it does today—intelligence. Intelligence has been a lifeline of the United States or any other country. You got to.

We knew what we were shootin’ at ’cause each ship has a distinct area that it’s supposed to target. It’s got a square of say six hundred yards‚ and when it’s going down that line of ships‚ they know where the guns are supposed to be trained and how much elevation to go to land. When they bombard with a naval ship‚ they’re putting shells in every little spot that they can in that little square. Each ship’s got a different area‚ and it’s lobbing them in.

Up in Kiska we had to lob over a mountain cause we thought the Japs were stationed up there‚ too. They mighta been‚ I don’t know. We was up there during the Midway. We had to target bracket that whole block that we were designated to shoot at. Every ship had a certain area. An attack force can go down an island and it can drop shells in every ten feet. Just go the whole area.

Kwajalien was our first thing that we did after we went out. Bombardments are at night. We don’t do it at daytime. I don’t remember ever running on a bombardment except at night cause the Japs didn’t have hardly any radar then. They didn’t even know we were when we would do this.

Coming back from Kwajalein‚ we came into Pearl and we got assigned to probably the best duty that a ship could have in wartime. We escorted the Matson Liners between San Francisco and Honolulu for maybe two months. All we did was go to San Francisco with a load of civilians‚ families that was out there. Not yard workers‚ I don’t imagine. They’d have to stay. We would transport all them people back with the Matson Liners. We weren’t by ourselves. We had cruisers‚ destroyers. Matson Liners were big commercial passenger ships.

We always went into San Francisco. We would load. We’d make liberty‚ and then we’d turn around and go back to Honolulu with nurses and other military people back out to Honolulu. We’d go into Pearl and load up‚ make a few liberties‚ waiting‚ and then when the Matson liners would take off we’d be out there waiting for it. Back to San Francisco‚ back and forth. You never could ask for better duty. We did that for a couple months. After that duty we made another bombardment run.

I never saw a Japanese submarine off the west coast‚ although we went to quarters and the destroyers went circling around looking for some. They detected something, I guess‚ but we never did see it. As far as I know they never sunk any Japanese subs on the west coast‚ other than those two–men submarines out in Honolulu.

The Japanese didn’t come that close. They didn’t get that close‚ to bring those two–man submarines. So we never saw a Japanese ship or no planes all the time we were transporting those back and forth. But we had to do it. There’s that old saying‚ somebody’s got to do it.

For the Midway battle‚ before that we were loaded up with Marines and we took them to Wake Island or Midway‚ one of the two. Maybe it was Midway. We took them there and unloaded them and from then we went up into Alaska. We patrolled and made a couple of bombardment runs on Kiskaand Attu and stayed up there until after the Midway battle.

We knew that the Japanese was going to attack the Midway Islands. We didn’t know from where. We didn’t know if they was going to come down from the north. There’s been movies and everything about Midway‚ well it was just on here recently. They found ’em coming from another direction. That’s when the big Midway battle happened.

A friend of mine in Columbus‚ who is a member of the Pearl Harbor Survivors’ Association‚ was on the West Virginia which was sunk at Pearl Harbor. He was to transfer to the Lexington‚ and he got that ship knocked out from underneath him at the Midway battle. So he had to abandon ship in two different ships‚ the West Virginia and the Lexington.

We stayed up there until that was over because at the time we was sent up there we didn’t know if the Japanese were gonna come that way or not. So we was up there to get ’em if they come that way. In the meantime we made some bombardment runs. We was up in the Bering Sea and all over that part of the country.