saltboiler

times

A Journal of Jackson, Ohio, for Wildflowers, Local History, and Travel

ralph cochran—

B–24 gunner and pow

RALPH COCHRAN

contents—click on a chapter

- 1—early life and enlistment

- 2—basic training

- 3—college training detachment

- 4—cadet training

- 5—armament school

- 6—gunnery school

- 7—crew training

- 8—bombing from england over germany

- 9—shot down

- 10—prisoner of war

- 11—liberation and back home

- 12—questions and conclusions

- liberators over europe—a video

My name is Ralph Hixon Cochran. Hixon is my mother’s maiden name. I was born on August 17‚ 1922‚ in Jackson County at the head of Petrea Hollow on old Route 124 about four miles out of Jackson.

I went eight years to a one room school up near the country club. It was called Poore‚ named after the man who owned the land where the school building was built. I spent my first eight years in this one room school‚ and then four years at Jackson High School. Jackson High School was located then in the same place it is now‚ only it was a much smaller building. The main part of the building is the same as it was when I went to school. I started there in 1936 and finished in 1940. Graduated in 1940.

My favorite subjects in high school were manual training and mechanical drawing. I enjoyed government and history‚ depending on the teacher. Two of the best teachers that I remember were Russell Jones‚ who taught mechanical drawing and manual arts‚ and Merrill Davis. Merrill Davis was probably tops in my mind because he was a good human being. He talked to me several times about life and what was going on‚ about choosing what to do when you get out of school‚ and that sort of thing. I could relate to him better than I did to some of the other teachers. I course I had a couple of teachers who kept telling us that if we didn’t work harder we’d be nothing but ditch diggers‚ and I always took that as a put down‚ and didn’t think that that contributed a whole hell of a lot to education.

I didn’t play sports‚ but I did a lot of tumbling in gym‚ playing in gym‚ but the organized sports... We lived on a farm and I had to work. I didn’t have any way to get into town to practice in the evening. I always wanted to do Glee Club and Band but you had to stay after school. We lived four miles from town‚ and I had work to do on the farm.

I have a brother that’s eleven years younger than I am. So it was just the two of us. And the parents. Both of my parents were living until recent years.

The four years I went to High School we had an old rattletrap bus that we rode. I had to catch it after school. If you missed the bus the only alternative was walk home. I had chores to do every night. We’d had a fruit and vegetable farm‚ and we had cows and sheep and horses and hogs and chickens‚ so there was a lot of stuff to do on this farm.

We were different from a lot of people I’ve met in later years. We never wanted for food‚ and one of the things I think the Depression did for me (and didn’t do for my brother) was in my formative years we had no access to candy and pop and stuff like that. It was stuff out of the garden. It was home raised. When my brother came along things were a little more prosperous. At that time my dad was running a little general store in connection with a road side market. So he had access to a lot of sweet foods and he had teeth problems that I didn’t have. So I think I was a healthier person because of the Depression.

That might be strange to a lot of people but we had all the fresh vegetables and all the fresh fruit we could possibly eat‚ so our diet was good. We didn’t have material things. If you got a nickel to spend and went to town‚ that was a real big deal. I guess the other thing the Depression did was create a problem in that we didn’t throw anything away because you might need it. If machinery broke down‚ why you kept the old piece because you might need it to fix something else. That ingrained habit is kind of hard to get over. This day and age you end up keeping a lot of stuff that you really should throw away. All of a sudden you have to stop and say hey I don’t really need this stuff today‚ and get rid of it.

It taught us I think to be thrifty. Taught us to be happy with not very many material things. I can enjoy life without material things. I spent a lot of time out in the woods hiking.

In school‚ we did not have things that school kids have today. We made our own playthings. We had a row of trees we played in. Some kids would find a piece of rope. Somebody found a tire‚ and we made a tire swing. We chopped poles and made a pole vault. Somebody brought a bat and somebody else found a ball. We made our own playthings.

We didn’t think about going out and buying something because we didn’t have any money. I think that carries through. Today we spend a lot of time thinking about buying something before we ever spend any money to buy it. I think that goes back to those times when we didn’t have much.

The year after I graduated I started to Ohio State University‚ and then the war started. I went a couple of quarters. It would be the Fall of ’40 and the Spring of ’41. I think it was two or three quarters‚ maybe the Spring quarter I dropped out‚ come back home to help out on the farm.

I was in horticulture. Horticulture was one branch of the Agriculture Department. The first couple of quarters I was taking chemistry‚ physical training‚ English. Very few courses on the major. Then I dropped out of school and came back home to work on the farm. I did that because my dad needed help on the farm. We had thirty acres of apple orchard. It was December of ’41. That was Pearl Harbor and a lot of young people were going into the service.

I don’t remember what I was doing in the fall of ’41 other than on the farm. In the Spring of ’42 I attempted to enlist in the Marines and my dad had to sign for me. He wouldn’t sign for me‚ so that fell through. Back then you had to be twenty-one.

Then I applied to get in the Air Force. I’m not sure of the date there. I had a cousin that lived with us for a few years. Their family broke up and a couple of cousins lived with my family. He went in the service early‚ one of the first people drafted. My reason for enlisting was this cousin was killed up in the Aleutians in combat with the Japanese‚ so I was pretty well indoctrinated with patriotism and that sort of thing. So I started work to get into the Air Force and was sworn into the Air Force in August of 1942.

I don’t remember any pressure to enlist. I don’t remember any comments or anything. What I did I did because that’s what I wanted to do.

My dad didn’t think I ought to go into Marines‚ and really it was lucky that I didn’t go in because a group of people that were inducted at the time I went in were practically all killed in the Battle of Iwo Jima. I probably wouldn’t have been here today if I had gone into the Marines.

My dad did not oppose all military service. He was in World War One and he felt everybody should do their bit‚ their part. That was part of my reason for enlisting. I looked at the Marine Corps first because it had a good air force and I was interested in flying. I guess their propaganda was probably better than anybody else’s‚ main reason. My father wanted me to wait until I was old enough to decide for myself what I wanted to do. Twenty-one years I think was the big deal. He wanted me to be able to decide what I wanted to do. I thought I knew what I wanted to do at that time. I wouldn’t do the same thing again if I had to do it over again. At that time‚ what I did‚ I did the same thing everybody does at the time. That’s what I thought I ought to do. I thought it was a good idea.

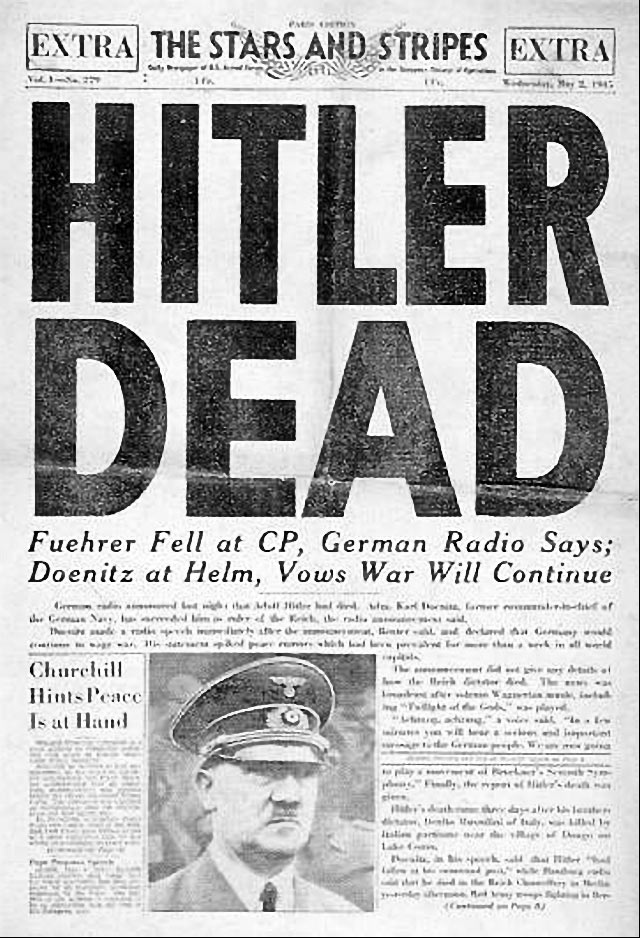

I didn’t know that I felt any fear when I went in. I guess the idea was I just wanted to do my part and by golly I was going to do it. I probably was influenced by the wave of emotion over the war. The paper was full of people that we knew that were getting killed and we didn’t know too much about what was going on in Germany. I didn’t know until after the war was over the extent to which the Germans had killed the Jewish people‚ but we knew Hitler was a bad egg. And we wanted to do something about it.

I took my physical examination in the old Post Office building in Columbus‚ Ohio. They told me to go home and they’d call me. They didn’t call me until January of 1943. I think we reported to Fort Hayes. That’s kind of fuzzy. We were put on a train‚ and went to Fort Benjamin Harrison. I don’t remember whether it was one night or several days.

Fort Benjamin Harrison was near Indianapolis. Then we were put on a troop train and shipped to Wichita Falls‚ Texas. Still in civilian clothes. It was that trip I learned a lot about the military. I had a real enjoyable trip from Fort Benjamin Harrison to Wichita Falls. I wandered around the train. That troop train had a cook car on it and they cooked with wood. Believe it or not‚ old telephone poles‚ sawed up into little short chunks. I got back into that cook car shortly after we took off from Benjamin Harrision. Was standing‚ looking out the open door.

On the troop train there were two seats facing each other‚ and there were three people for those two seats. You couldn’t get comfortable. Particuarly me with my long legs. I couldn’t get comfortable‚ so I went back into this cook car and I asked the cook if I could look out the window. There was fresh air.

After a bit he come by and he said "I’ll be coming through the cars asking for volunteers. If you want to ride back here with us‚ why you volunteer. All the guys will hoot and holler." We knew all about that volunteer stuff‚ and so he said‚ "If you want to come back here‚ just volunteer." So when he come through‚ I volunteered and spent the ride in the cook car all the way to Texas. My duty was to every once in a while to stick a stick of wood in the stove. I could lay down on the floor and stretch out and sleep.

So I learned a lesson in that when you volunteer‚ you don’t always end up on the short end of the stick. There were times to volunteer and times not to volunteer. That was an enjoyable ride. I think it took us three days and three nights. That was where I had basic training. That was where I learned that the military was not my bag of bones.

At that point in time‚ they were running people through basic training like water through a sieve. I’d say the training was good. The training I got in the Air Force was good all the way through. It was excellent training. But we were really under pressure‚ and it was from daylight until lights out at night. Practically at a dead run‚ we were either studying or in lectures. Out drilling or doing physical training.

I think that we got about the same thing everybody going into any military organization got. That was the basics of military protocol‚ military courtesies‚ the technique of marching and all the different military commands. The study of the Army regulations. What you were required to do. What you could do and what you couldn’t do. A little bit of familiarization with guns.

We fired the old Springfield rifle and we fired the Thompson submachine gun‚ which was a really nice weapon. Then we fired the gun that come out‚ was popular in the war. They called it the grease gun. It looked like a grease gun. It spewed out a lot of bullets but wasn’t very accurate. We practiced with a Colt .45‚ firing it‚ taking it apart. All of the guns we took apart and put them back together. Basic stuff.

It was a little over thirty days. Part of the time was used up getting uniforms‚ clothing‚ learning how to make beds‚ how to fold clothing and how to wash floors. Doing KP. Taking shots. They started through a whole series of shots for everything you could think of.

Best I can remember in Wichita Falls they were single story barracks. They were tarpaper shacks. We went by flights‚ squadrons and that sort of thing rather than the nomenclature used in the Army.

Hell‚ it was a big base and I don’t have any concept of the base‚ because we went into an area and we were quarantined or confined to that area. We were kept so busy that I did not get into Wichita Falls‚ which some people said wasn’t worth going into. I don’t know. It was probably the worst place I have ever been in my life in terms of climate.

This was in January and the beginning of February‚ and there’s where I learned that the Army wasn’t something I wanted to do after the war got over. In the morning when you got up it was cold. It would just be freezing cold. Somebody decided what you were to put on. If overcoats were the dress‚ then that’s what you put on. By nine or nine thirty maybe ten o’clock‚ you could run around in your shorts. It was hot. But by golly the uniform was overcoats‚ and so when you fell out after lunch somebody decided that you were to wear just a shirt and pants. By three thirty or four it began to get cold. It would freeze your ass off before you got back to the barracks if you were out drilling or doing something else.

So I found out you didn’t take care of yourself as an individual. You did what somebody else wanted you to do. That wasn’t anything I wanted to do any longer than I had to do it.

The other thing was‚ it was dusty. There was dust filtered through the windows. It was in blankets. It was in the food. You marched and drilled in the dust. There was one day when we actually had a downpour of rain. Rained real hard. The wind shifted around to the north and started to blow. The wind was carrying dust out of Oaklahoma and we were actually marching along in mud choking on dust.

Everybody had what they called dust pneumonia. You cough and your nose was running. If you went on sick call you got a dose of castor oil. The objective was to discourage people from going on sick call. You had to be pretty damn sick in order to go on sick call. Although it was a miserable period of time in terms of weather and the climate and that sort of thing‚ as I remember I thought the food was okay and I thought the training was adequate. They were serious about it and instructors were good. Some of them were a little bit oppressive at times.

The sergeants were not physically abusive. Mostly it was verbal abuse. After I once found out that that was just a standard part of training procedure‚ you didn’t pay much attention to it. I wouldn’t consider it abuse. I was never abused—anything that I could call abuse. I don’t remember any instance where somebody who was in charge physically touched someone else. Usually it was all verbal. Really chew you out kind of thing‚ but physical‚ no.

The one conflict that I had‚ and it continued during the period I was in military service‚ was my experience with the Red Cross. The first pay that we received in Wichita Falls when I went through the pay line‚ there was a desk and it said “Red Cross” on it. We weren’t getting very much money at the time. I did not desire to contribute to the Red Cross‚ so I started past the desk. There was a Lieutenant standing there and he stopped me‚ and said‚ “Soldier‚ you forgot to make your contribution to the Red Cross.” Well‚ somehow or another that rubbed me the wrong way and I learned a couple of lessons from that. I said “Sir‚ I do not recall where the Army Regulations specify that I have to contribute to the American Red Cross‚ ” so he let me pass.

I learned that that didn’t do me much good because I got a lot of shit details after that. I didn’t contribute to the Red Cross. From there on my feelings toward the Red Cross went downhill. It was just one bad experience after another and that was the beginning of that. I was a shy country boy; at least I held my ground on that issue.

I don’t have any personal bad memories of basic training‚ other than the weather and the dust.

I saw guys get hurt on the drill field and were ordered back on their feet and just keep right on going. I saw a guy fall and cut his hip with a piece of glass‚ and he wanted to quit and go get it fixed‚ and they ordered him right back in formation and kept right on moving.

That flipped something else into my memory. One thing‚ I did get the wits scared out of me on the firing range. I grew up on the farm and I don’t remember when I didn’t have access to a gun. Seems I grew up with guns‚ to hunt. One of the rules I learned as a very small child‚ was that you don’t point a gun at anyone else. You be very careful where you point a gun.

When we got out on the firing line‚ it was downright scary. Some people didn’t appear to know which end of the gun the bullet come out of. There were occasionally somebody that got shot or got hurt by taking a gun and turning it around and asking a question about it and the barrel was pointed down the line at people who were firing.

It always frightened me going out on the firing range because of people’s ignorance about guns and how to use them. That’s one of the things that taught me to believe that there ought to be some rules regarding the use of guns in this country‚ or the freedom of which people can get guns. I don’t think that the great majority of the people have any reason to have a gun‚ because they are not trained to use it. That experience probably influenced my thinking about gun control. I think there ought to be some controls on guns.

My training unit was a real mixture of people. I would guess I was in with more Texans and Southerners than I was with Midwest people‚ and I really don’t know how that come about.

I did not go in with any friends. The people that I was friends with in basic training were some of the people that I met on the troop train‚ going down. I really didn’t meet very many people on the troop train because of being in the cook car. Most of the people I met were people in basic training. I think throughout my military career it was a mixture of people from all over. Probably more southerners than people from the midwest or north.

I don’t remember that we had time for recreation in basic training. I remember once in a while there were some ball games going on. Mostly if there was any free time‚ most people took any free time to catch a few winks of sleep or rest or write letters home or something like that. They were running us through training so...my impression was that there was so much pressure to get the training done as fast as they can possibly do it and still provide some decent training. There wasn’t a lot of time for organized sports and stuff like that. We did not get any passes. At least the group that I was with didn’t get any passes.

I did not see any black people there. There was an incident on the base. I was not involved in it. All I knew was I heard about it. There was a black officer on the base. A soldier did not salute him‚ and it turned out to be a Texan. I remember the guy said‚ “You put your hat on a post over there and I’ll salute the hat‚ but I won’t salute you”. That kind of a thing. That was a long time before there was any thought of integration. A lot of the people that I was with were racist. They were racist in terms of blacks.

The other bad part of basic was that they didn’t have shoes to fit me. I had to wear my civilian shoes till they fell off my feet. I wear a size fourteen shoe and I had a pair of Florsheims that were practically new. I got chewed out every day because I didn’t have regulation shoes. My standard answer was “Sir‚ if you find me a pair of shoes‚ I’ll just be tickled shitless to wear them.”

Finally a jeep pulled up in front of the barracks one day and a great big old fat master sergeant got out and hunted me up. He said‚ “I’m going to fix you with a pair of shoes‚ boy.” So they took me off to a warehouse and I got two band–new pair of shoes that fit perfectly. This guy spent all afternoon fitting me with this pair of shoes. He said‚ “You don’t want to drill or do anything‚ ” and he said‚ “Takes a lot of time to make sure the shoes fit.” So really I got one afternoon of goofing off getting a pair of shoes. I kept those pair of shoes till I was shot down in Germany. I was told to never let loose of them because I might never get another pair of shoes that fit.

From basic training I went to Wichita‚ Kansas‚ and I spent three months in the University of Wichita in what they called a college training detachment. There we spent three months studying physics and aerodynamics and airplane engineering‚ airplane identification‚ and a bunch of subjects relating to theory about airplanes and flight and guns and bombs and this kind of stuff.

I went to Wichita probably late February or sometime in February or March. It was the University of Wichita and they had bunk beds set in the gymnasium. There was about five hundred GI’s there‚ all of them taking the college training course. That was to give us some technical knowledge that we needed to know to be in the Air Force or Air Corps. Understand the function and operation of planes and so on.

We went through a physics book--was about two and a half inches thick. We went through that in three months. So you know‚ we hit it pretty light in terms of in–depth stuff. Their emphasis was on the kind of things they thought we needed to know. Some basic understanding of the function of mechanical things‚ and all that physics encompasses.

I thought this training was worthwhile. I have always felt that any and all training and all knowledge is helpful. I feel that it is sort of like a jigsaw puzzle. You never know when a little piece will fit somewhere. I felt that all the training I had was beneficial. Some of it was something that I would never use‚ but had I needed it‚ I had it.

The Wichita training lasted about three months. It was good. The food was good. There was a major in charge of the unit and he came in unannounced. Walked up to the chow line and walked through. He demanded to be served exactly what the soldiers‚ the GI’s‚ airmen‚ were being served. God help the cooks if it wasn’t good. So we really got good food. Most places that I was in the Air Force‚ the officers ate separately and were served separate meals. They ate at a table maybe in one corner of the mess hall and they got special meals. But on that particular unit we got really good food.

It was a highly disciplined outfit. This was in a civilian area. There weren’t very many military people‚ particularly around the campus or in the area around Wichita. So we were expected not to walk down the street smoking cigarettes. We were expected to always be in uniform. Wear a tie‚ hat.

This major‚ his method of operation was real good. He told us in the very beginning that “You can do whatever you want to‚ but if you were caught smoking on the street‚ you can take a weekend. Set it up on the mantel. You’ve lost that. If you prefer to smoke on the street and give up your weekend‚ beautiful‚ go right ahead.” He had a whole list of things he expected people to do. If you wanted to go out at night without a pass‚ go ahead. If you don’t get caught‚ fine. But if you do get caught‚ you are going to lose. You can just set that up on the mantel. You know you’ve done lost it.

So the military discipline there was really good. People stood up and flew right. Everybody felt they got fair treatment‚ even though it was pretty strict discipline. It was an enjoyable experience. Every weekend we got to go into Wichita. Wichita was a dry town so there wasn’t any drinking. I shouldn’t say there wasn’t any‚ but there wasn’t as much drinking and carousing around as there were a lot of places where military people were.

Another asset‚ every week this major had arranged. There was a club or something in Wichita that had a dance band‚ a new dance band every week‚ like Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller‚ the real top dance bands of that era. Every week they would appear on the stage at the University and do a half hour radio program. Then they would do a half hour program strictly for the GIs. That was a real thrill‚ an experience to see all these name bands come. Yeah. Their half hour on the air was always very dignified and so on. The half hour that they stayed and played for us they really let their hair down. They told all kind of dirty jokes and had fun and raised all manner of hell.

I don’t remember many girls there. There were lots of females in town‚ but I don’t remember a student population. I don’t remember whether that was because we were pretty restricted to a specific area. We weren’t mixed with any student population or any civilians. We were in a little area and we were confined to that area. Except when we got a pass to go to town. There was supposed to be five hundred of us. We were in a great big gym and we were rammed in there in double deck bunks‚ one against the other. I don’t remember people coming in and going out. There was a whole group of us.

piper cub

piper cub

There was one incident that I want to tell you about. We took flight training when we were at Wichita in a Piper Cub. I had heard stories about this‚ but I actually saw a plane land backward!

One of the things that I did not like about Wichita was the wind blew almost constantly there. Coming from hill country I wasn’t used to steady wind. I was used to gusty wind. But you could literally go out and throw your hat up against a building and it would stay there. The wind just blew steady.

Well‚ they had a storm‚ through the Midwest and they were flying some planes in there from Texas. There was a Piper Cub come in and circled the field‚ and throttled back. It was blowing hard enough that he actually backed the plane onto the ground. There was about twenty of us went out and grabbed the wings and the tail and held it down until he shut the engine off and he could get it over and tie it to the ground. That was the last plane that landed that day.

It was a real thrill to see that happen. The wind was blowing hard enough and the steady gusts‚ that he just throttled it back and let it settle down on the ground. That was all that was talked about. Probably never ever see anything like that again in their lives. We all agreed that if we told it nobody would believe us.

I think while I was there I had somewhere between six and ten hours of instruction in a Piper Cub. Little two–seater job. This was to give us some feel for an airplane. Basic idea about flying‚ the fundamentals of a plane. We were studying aerodynamics and all this stuff that’s involved. Things that have gone foggy in my mind. I’d have to read up to talk with any familiarity. A lot of that stuff.

It was a selection process really. And the selection process started from the time you went into basic training. There were a lot of people got sifted out somewhere in basic training. What happened to those people I don’t know. Each step along the way there was people that went in different directions. After the college training detachment there were people went into navigation‚ people that went to bombardier school‚ cadet training for pilot. People went to radio school‚ gunnery school‚ armament school.

All the time in the Air Force you were taking tests‚ and sometimes you didn’t know what the heck the tests were all about. But you were taking tests and being evaluated. If you were a person who had six thumbs on each hand when it come to taking guns apart and putting them back together and that was part of the way you were wired up‚ why you would not get channeled into some area where you had to use manual dexterity. You’d get channeled somewhere else.

The Air Force was reasonably successful at this. When we were finally put together as a crew (and I never really thought about this before)‚ the guys on our crew‚ with one exception‚ were good at their jobs. We had one of the best pilots in the Air Force. Our engineer‚ he was one of these guys like‚ we’ve got a few around Jackson County‚ that can fix anything. They haven’t got a great school background but they can look at a piece of machinery and they just know what’s wrong with it‚ and they just seem to identify with engines. They understand engines. That’s the way with our engineer.

The radio operator could send and take code and there was times I would have the headphones on and I couldn’t hear anything except a God awful mess of static and noise‚ and he’d be writing a message out of all that crap. He was really good. We had one exception on our crew. We had a kid from New York who would only do what he wanted to do.

When there was a check on the crew to see how everybody was when we were in the air‚ he just wouldn’t bother to answer. So when we started overseas‚ we told the pilots we weren’t going to fly a mission with him. He was taken off the crew and another man put on. Couldn’t depend on him. You didn’t know what the hell he was going to do. He seemed to know his job and so on‚ but he just wasn’t cooperative.

No‚ he wasn’t one of the team. He didn’t fit in‚ but from that experience‚ I’d say at least in the little bitty area where I got involved in and knew about‚ it seemed to work. People got put into slots where they fit.

We had a guy who was a cook‚ never went through basic training‚ was a cook on our airbase in England. They needed a gunner and they said "Tony‚ you’re the gunner." They put him on crew. He flew a couple of missions with us. He was a good guy. He said "I don’t know a damn thing about anything‚ but they tell me I’m a gunner." So he was real cooperative and other people kept him propped up to do whatever he needed to do. But he never had any gunnery training. He never had any basic training in the Army. He went in as a cook.

There’s one bit about training that I would like to relate to you. I was impressed with the military’s technique of training. I think that a lot of training operations go on that could have learned a lot from the military’s way of teaching. It wouldn’t work on everything‚ but it would work on many things. Basically‚ whatever we were studying‚ you had somebody explain what it was all about to you and if it was possible‚ showed you pictures. They showed you what to do. Then you did it. Then you talked about what you did. Then they gave you materials to study.

Particularly with things like guns and bombs and airplanes and so on‚ we learned skills in a matter of days that would take months and even years in civilian life to learn‚ because you really got soaked in it‚ in effect. Somebody told you about it‚ and they showed you‚ and they had you do it.

The medics‚ for example‚ they taught people to do things as medics in the service in a matter of a few weeks that only doctors do now in civilian life. They told you all about it. They showed you how it was done‚ and then you practiced on an orange or you practiced on something. Then you talked about what you did‚ and then you practiced on each other. You learned damn fast‚ because if you screwed up with the guy you were shooting a needle into‚ he had the next turn on you. If you screwed up on him‚ you got back double if you were a medic.

With guns‚ in a matter of hours‚ you reached the point where you could take them apart and put them back together blindfolded. It was the same thing about flying airplanes‚ bombardiers or navigators. They studied about it; they saw it; they did it and then they talked about what they did. Then they kept doing it over and over and talking about it and going back and seeing it again. It’s a technique of training that was really effective. It could be used a lot more of that kind of technique to teach things. It’s used sometimes.

I graduated from Wichita about in May‚ maybe. Then I went to San Antonio for cadet training. I passed a test in Basic. We had tests in Basic and that was a first step. The college training detachment. Then from there I went to cadet training in San Antonio and I washed out of cadet training. Let me give you a thumbnail sketch of what happened.

Cadet training meant we were being trained to be either a pilot‚ bombardier‚ or navigator. It was an officer training program‚ and here again people went in all directions. Some of the people all in a class went on to pilot training‚ which was what most of the people wanted to do. A bunch of them went to bombardier school. Some of them went to navigator school. A lot of them like me went to various other jobs. Either gunnery school‚ armament school‚ mechanics school‚ radio school. A good percentage of the people I met who were radio operators and engineers had been in some phase of cadet training.

Cadet training was more intense. We got into a lot more serious flying strictly to fly. We got into things like what happens when you go up to altitude and the oxygen in the air decreases. After you reach a certain height‚ you pass out. We were all given an opportunity to experience what happens. We were taken into pressure chambers and got to watch other people. What their symptoms‚ what the heck do you call it‚ anoxia‚ it that right? It’s a good way to go. You feel euphoric. You feel great.

But a shot of oxygen and you’re back okay. I passed out one time on the gangway in the bomb bay in a bomber. The engineer was watching me and grabbed the oxygen mask and shoved it on my face. If you’re without oxygen for a long enough period of time‚ why you just don’t wake up anymore.

All those things that happen to you physically‚ we got training on. There was a lot of theory about planes and how they flew and so on‚ and there was a hell of a lot of physical training. As I remember‚ almost half of every day was devoted to physical training and drill‚ marching. We had a dress parade almost every day‚ and we had a couple of hours of physical training.

obstacle course

obstacle course

We did a lot of pushups and jumping jacks and running‚ and they had what they called an obstacle course and then there was another thing where we ran over a long distance. We had physical training and then we had to go in and shower and put on dress uniform and fall in and get everybody organized and lined up and then passing review kind of thing. Involved a good bit of time and it probably seemed a lot longer than it was.

Some of the crazy things that happened. One day when we were having dress parade there was a guy from St. Louis by the name of King Fishman and he was a tall guy same as I am. We were usually in the front row together. He had a buddy standing that was between us and his buddy whispered to both of us‚ and I don’t remember his name. He says‚ “I’m gonna faint‚ pass out‚ and you guys carry me off the field.” This was shortly after we’d gotten to San Antonio. So he keeled over and King got one arm and I got the other and we helped him off the field. Went around the barracks and got a drink of water and set on the steps enjoying ourselves while the rest of these guys were passing in review. It was about a hundred and two in the shade down there.

After the people were dismissed‚ after the dress parade‚ the lieutenant in charge of our group come around the barracks. He said‚ “All right‚ you sons of bitches got away with it today‚ but if you ever do that again‚ I’ll crucify you.” We never did that again. He said‚ “If somebody passes out you leave them lay. If you have to step on them you walk right over them.” He said‚ “You don’t bend over and pick anybody up when you’re in dress parade. If they pass out that’s their problem.” We felt we were lucky we didn’t get penalized a little bit more for doing something which we knew was illegal.

He had faked it. But everyday there was guys all over the place passing out from the heat. Apparently one of the things that would happen‚ people would come in from PT. It was hot down there in the summer‚ late spring‚ summer. It was really hot in the middle of the day in San Antonio. Guys would come in hot‚ and go in and take a cold shower and then drink some ice water and then put on a dress uniform and go out on the drill field. They used to tell us not to lock our knees. I never knew why they did that‚ but they said that cut off the circulation. That was the only explanation I ever heard.

That doesn’t sound to me like enough to make you pass out‚ but they said not to. You stood at attention‚ but you stayed loose. Anyway‚ a lot of guys would pass out from the heat‚ and just keel over. They let you lay there until they dismissed the troops. You just stepped around the guy in front of you if he fell over. If he didn’t come out of it‚ why after a while the medics come along and pick him up and cart him off. But I never had any trouble with that. I never took a cold shower. I always took a hot shower and didn’t drink cold water‚ and I never had any trouble with the heat.

The course at cadet school was twelve weeks‚ but I’m not sure about that. They had classes every day to learn Morse code. I could never pass the test‚ and I thought I was just stupid or something in terms of getting it. I’d gotten everything else all right. Finally they sent me to another air base and I went and had an auditory examination. There was a whole range of tones that I don’t hear. Like this telephone over here. I don’t hear it‚ and the doctors told me‚ “There’s no point in you trying to do Morse code. You could do it visually‚ but you’ll never do it‚ because you do not hear to distinguish between dits and the dashes.” So that was the end of that.

I washed out of cadet training because I’m tone deaf. I could not take code‚ and that was one of the basic requirements. That you be able to take Morse code. I couldn’t distinguish two dits from three dits or four dits. There’s a whole range of tones that I don’t hear. I didn’t find that out or didn’t know that until I got into cadet training.

ball turret

ball turret

When I washed out of cadet school‚ as I remember they asked‚ “What do you want to do? You got some choices here. You want to go to armament school?” “Sure. That’s a good place to go.” I had requested to go to gunnery school. They said that there was no point in going to gunnery school. You can’t. You’re overweight and you’re too tall. Back at that time they were thinking about gunners flying the ball turrets in B-17’s and B-24’s. There was very little room in those turrets and I think that was one of the reasons for the height and weight restrictions. If you were too tall and couldn’t fit in that thing‚ that limited the choices they had to assign you. By the time I got overseas in the Liberator bombers‚ they weren’t using the ball turrets. They were taken out of the airplanes. They weren’t using them so it didn’t make any difference anyway.

I still wanted to fly‚ but they told me I was too tall and too heavy. I weighed too much. The limit was six feet and one hundred eighty pounds‚ and I was six one and a half and one hundred and ninety. So they sent me to Denver‚ Colorado‚ to armament school. There I studied‚ learned all about turrets‚ gun turrets‚ and machine guns‚ caliber .50 machine guns‚ and bombs and bomb releases and electronics on bombers and everything that had to do with the armament‚ and that part of the bombers. I still wanted to fly. They wanted me to become permanent party and become one of the instructors. I didn’t want to do that.

Lowry Air Force base in Denver‚ Colorado for armament school. That was a twelve week school. That was for in–depth training on all of the things on the airplane that have to do with armament. As I remember‚ the bombers that I was familiar with all used caliber .50 machine guns. The bomb racks—the brackets that held the bombs—and a lot of the stuff was common. We also took a look at different individual airplanes and the differences between the armament on the different airplanes.

As a result of my training‚ I could have gone into B–24’s‚ Liberators‚ which I did‚ or B–17’s or B–26’s or A–26’s. Whatever bombers they were using at that time. One of the things that tickled me about Lowry‚ there was real high security on the Norden bomb sight. It was kept in a vault and there was all kind of restrictions on the material they handed out.

norden bombsight

norden bombsight

One day we went in town on an afternoon pass‚ picked up a Popular Mechanics magazine‚ and it had a better detailed drawing and description of the Norden bomb sight than we had on the air base. That was kind of interesting to me that the military would have restrictions on it and yet in the popular press they would have the details. I think the military was a little bit behind. At that point in time that bomb sight was not that big of a secret.

Anyway‚ I enjoyed the classes there. They got into the electrical functioning of the bomb release mechanisms‚ that sort of thing. It was good training. They had good instructors. This training was more intensive than the previous training. Looking back on it‚ and I never really thought about it‚ intensive is the wrong word. It was more in–depth‚ I think. Since you caused me to think about it‚ there was two processes that went on during the training that I had in the Air Force. One was that as the training progressed it got more in–depth. It couldn’t have been more intensive. It was intensive from the time I was inducted until I got back from overseas‚ but it was more in–depth.

There was also the selection process going on continually‚ in terms of sorting people out‚ making an attempt to get them into the slot where they fit insofar as possible‚ where they wanted to be. Of course during wartime in the military it is not possible for everybody to do what they want to do‚ and it’s also not unusual that a square peg got in a round hole. But‚ for most part I think the whole process was amazingly successful.

Lowry was just a big air base. A lot of barracks. There was a runway there‚ but it really wasn’t used as an airfield anymore. It was a big training installation. They had a big women’s army unit there‚ training. I don’t know what else. The part I was involved with was all armament.

It was a nice place to be in terms of climate. Back at that time we were about thirty miles from the mountains. You could get up in the morning and go out on the barracks. At Lowry the barracks were double-deck barracks. You could go out on the porch and you could look off and see the mountains‚ in the morning. It looked like you could walk over there to the mountains before breakfast‚ but the mountains were actually about thirty miles away.

The air was real clear. I think you could go to Denver now and you probably can’t do that. There is some smog‚ I understand‚ around Denver‚ but I loved the climate out there. I felt good there‚ humidity was low. It would be cold in the morning‚ but it warmed up during the day.

I liked the people around Denver. They were friendly people. It was quite a change from Jackson County. It always seemed to me that if you were a newcomer and moved in this part of the country‚ that you had to live here awhile and get acquainted before people really accepted you. It seemed that the people in the west...people I met in Denver and out in the country around Denver‚ ranchers and so on...they accepted you at face value. If you turned out not to be a real good person‚ they would reject you‚ but they tended to accept people on face value. I really enjoyed my time in Denver. It’s one of my favorite places when I was in the service.

As the best I can remember‚ we would spend the mornings in classroom and maybe some of the afternoon‚ but a good part of the afternoon would be devoted to physical training and drill. Then in the evening‚ as I recall‚ we spent a lot of time studying books and so on.

We weren’t as restricted there as we were in a lot of other places. Once a week we got a pass for a half a day. Go to town at noon‚ be back by midnight. The pressure wasn’t quite as heavy in armament school as it had been in basic training and some of the other training we had.

Today I was trying to figure out the date I graduated from armament school. It was a twelve weeks’school‚ and I did find the date that I arrived in Denver. October 21st. Of ’43. It would have been twelve weeks‚ so that was probably around February that I left Lowry‚ and went to gunnery school in Laredo‚ Texas.

I got sick‚ and the doctors called it bronchitis. I had a real bad cold‚ congestion in the lungs. And was in the hospital for a period of time and I lost a lot of weight as a result. The hospital was over at a different air base called Buckley and when I got back to Lowry‚ I immediately went down and asked for a recheck on my physical. I lost a little over ten pounds‚ so I went back and said that I wanted to retake the physical to go to gunnery school. When I went in for the recheck‚ the doctor said‚ “You really want to go to gunnery school?” I said “Yeah‚” and he said‚ “Well‚ hell‚ you’re not a hundred and ninety pounds. You look like you’re just about a hundred and seventy–nine.” “You can’t be over six feet”‚ so he changed the figures on the paper and I ended up going to Laredo‚ Texas to gunnery school. That’s when I got passed for gunnery school.

When you graduated from armament school‚ you could be a ground crew member working on the ground. In my case‚ I went from there to gunnery school. There were one‚ two‚ three‚ four gunners on the bomber‚ but I was the gunner in charge of the armament‚ because I had had specialized training in handling the bombs. There was a tail turret gunner. There was a waist gunner. I usually flew as one of the waist gunners. There was another waist gunner‚ and there was a nose turret gunner. The engineer flew the top turret.

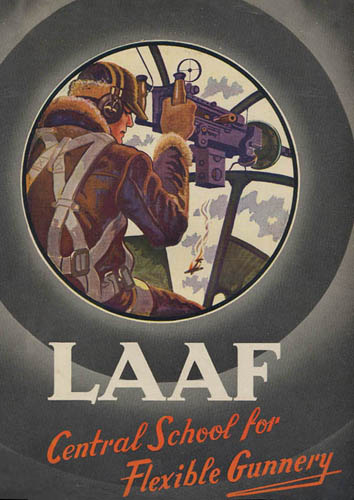

laredo army air field gunnery school

laredo army air field gunnery school

In gunnery school we spent several weeks shooting at clay pigeons. They had a circular track and you get in the back of a pickup truck and ride along. The clay pigeon would come from someplace. It might come straight at you. It might be going straight away from you. It might be going at an angle‚ all different angles. So we shot up thousands of rounds of shotgun shells shooting at clay pigeons from different angles to get the idea of tracking a moving object.

We flew out over the desert in AT–6’s and strafed targets on the ground with caliber thirty machine guns. One of those rides was almost my last ride. I went out on a strafing run and was standing up shooting over the side at a target. Whether the pilot maneuvered the plane or whether he hit an air bump or what the heck happened‚ the plane made a quick dip on one side and whipped back the other.

texan at–6

texan at–6

The gun butt caught my chute chord. I had on a seat pack‚ and it pulled the rip chord. I looked down and there was white silk coming out between my legs. The thought occurred to me that I was strapped to the bottom of that plane. There was a strap anchored to the bottom of the plane and hooked around my chute harness. The thoughts of that chute getting out in the airstream—so I let loose of the gun and sat down as quick as I could and started poking silk back under me.

The pilot was raising hell because I wasn’t finishing the strafing. The mike between his cockpit and mine didn’t work‚ so he finally give up and went back to the base. When we landed he jumped out and started cussing and said‚ “What in the hell is the matter with you?” He looked over in the cockpit and saw all the parachute laying out on the floor‚ and he said‚ “I see.” He helped me out and I slid off of the wing and slid down on the ground. My legs give way. I did all right as long as I was in the airplane‚ but when I got out it scared the hell out of me. That was the last strafing run I went on. Other than that‚ gunnery school was a lot of fun‚ but after a while it got old‚ shooting every day.

The gunnery school was in Laredo‚ Texas‚ down on the border between Texas and Mexico. The Mexican town across the border was called Nuevo Laredo. It was desert country there. Real hot‚ sandy desert kind of country.

I was there at least a couple or three weeks waiting to get into a class. They ran people through the school. It wasn’t that long. It seems to me it was only about a month‚ but I had to wait several weeks before I got into a class. I did find some of my flight records. I was in Casper‚ Wyoming‚ for phase training‚ that is‚ training as a crew‚ in May. Probably about the latter part of April.

I don’t know whether you are interested in crazy things or not. By that time I had begun to learn a little bit about Army life. We were in holding squadrons waiting to go to class. Every school that I went to‚ you got into this holding process. Where you were waiting to go into a class‚ and they wouldn’t give you a furlough home. Why‚ I’ve never understood.

Sometimes it would be several weeks‚ and so they made up work details and made work. When I was in San Antonio‚ one of the worst examples was that they called us out one day and we were required to go over the squadron area and break off the grass two inches high with our fingers on our hands and knees. Then when we’d covered the squadron area they brought a truck load of lawn mowers and made us run the lawn mowers over the grass we’d already broken off. Which was broken off below where the lawn mowers cut‚ but we had to run the lawn mowers over it.

I experienced that kind of stuff in San Antonio. I found that I didn’t like to do that so there were one story barracks‚ and I found it interesting to crawl under the barracks. The barracks was about two feet off the ground‚ up on blocks‚ and I spent a lot of time watching the ant lions making little cones in the sand. The different insects under the barracks. I found that more pleasurable than breaking off grass or picking up nonexistant cigarette butts.

What I was going to tell you about Laredo. I think it was maybe the second day we were there‚ we fell out and they picked people for details and they picked me to plant grass outside the squadron headquarters. It was obvious‚ looking at the ground‚ that there had been many attempts to try to plant grass. It was pure sand and there wasn’t anything that would grow in it‚ because they didn’t have water to irrigate it.

I was detailed to plant grass outside. The lieutenant took me out and said to plant the grass. It was over a hundred in the shade there. He had a nice office with an air conditioner in it. He said if I had any questions to ask him. So I waited until he got back into the air–conditioned office. I went in and said‚ “Sir‚ I don’t understand what I’m supposed to do out here.” He came out and he explained it to me and he went back in. I waited about five or ten minutes and I went back in and I said‚ “Would you come out and see if I’m doing it right?”

gunnery school patch

gunnery school patch

Well‚ he come out. I had taken this Bermuda grass and I planted it upside down so the roots were sticking out. He looked at that and he said “You are the one dumbest goddamn soldier I’ve ever seen. Get the hell out of here and I don’t want to ever see you again!” That was what I was waiting for‚ and so I went back to the barracks.

The next day when we fell out for detail‚ this lieutenant come down the line assigning people for different jobs and when he come to me he just went around me as though I didn’t exist and went on down the line. I spent the rest of the time while I was at Laredo in the library. I found that on a military base the library was the last place in the world anybody’d look for people goofing off. The librarians were so tickled to have somebody come and look at their books that they never said anything. From the time I found that out‚ anytime we were in holding squadron‚ why the library was one of my favorite places.

I found also that if I got in a formation‚ usually being the tallest person in a group‚ I was always the first man in the line. When we were marching down the road‚ invariably the sergeant that was in charge of the column would yell‚ “Column right”‚ and turn around and watch the tail end of the column. Well‚ I found that if I just kept going straight ahead‚ that the fellow behind me would step up in my spot and the whole column would do a column right and go on. Then I would go straight on down to the library. I never did get caught. I always figured that if they caught me I would pretend I didn’t hear or understand.

I found out another thing. On most military installations if you went around with a clipboard and pencil‚ most people would leave you alone because they didn’t know what you were checking up on or what you were investigating.

Walk around and look like you know what you were doing. I never did meet anybody else that liked to go to the library. I loved to read and very rarely would there be anybody else in the library. You could get away from them without getting caught. There were so many people going through that they never got familiar with your face or your name. You’re just another soldier.

shotgun gunnery practice

shotgun gunnery practice

Gunnery school‚ we specialized on shooting. I think I mentioned the other day‚ we shot thousands of rounds of shotgun shells practicing shooting at moving objects from different angles. So we’d instinctively know how far to lead the object‚ either over‚ under‚ or in front of it. Practice with individual shotguns‚ then practice with shotguns mounted in turrets on the trucks.

We were in a regular turret just like in a bomber. Have two shotguns mounted where the machine guns were. When you were looking in a gun sight‚ and the controls were down here‚ and so you were moving that thing around tracking clay pigeons. Then there was strafing from the back cockpit of an AT–6‚ shooting at targets on the ground.

gunnery practice vehicles

gunnery practice vehicles

There were a few instances where the pickup truck was moving. Most of the back of the pickup truck stuff was where you were standing in the back of the pickup truck. There would be four or five guys in the back of a pickup truck and you’d have shotguns‚ and it would go around the circular track. I don’t remember how fast. It wasn’t very fast. But there would be clay pigeon houses located in different places along the track and at some of them the clay pigeon would come out and the clay pigeon would come straight toward you from a distance. So the clay target was coming towards you and it was also rising as it come towards you‚ and then when it reached a certain point it began to drop. Then there would be one come out to the left‚ to your left‚ facing it and the truck was going in the same direction as the target‚ so you were shooting at a target that was moving in the same direction as you were. The next one would be a target going to the right—you were going in one direction and the target was going in the other direction. So you had to double your lead. Then maybe the next one you’d come to would be one going straight away‚ and that situation‚ you were moving in one direction and the target was moving in the other direction and going up as it moved. So you really learned how to shoot.

In the beginning I hit the clay bird very rarely. After you practiced enough‚ and the instructors told you what to do‚ how you were to lead in one of those situations‚ it was amazing how many birds we broke. As I remember‚ in the turrets‚ most of that was standing still. The turrets were mounted on‚ like about a ton and a half trucks. They were bigger trucks‚ because they had a big turret mounted on it‚ and the electrical stuff to operate the turret.

.50 caliber machine gun

.50 caliber machine gun

We also had a lot of aircraft identification classes. We really got into guns‚ particularly the caliber .50 machine gun. Taking the thing apart and putting it back together‚ and studying all the different possible things that could go wrong with it. What you did‚ or how to recognize what happened‚ and then how to fix it. Here again‚ that was good training. All through the training‚ I took the training seriously. I think for me that was an important thing‚ and it saved my life. I did take training seriously.

After gunnery school‚ I was assigned to a crew and went on to what they called phase training. The objective was to take a group of people and put them together and make a crew out of them. So they cooperate and get to know each other and that sort of thing.

In the Liberator bomber‚ it was typical for one of the gunners to be responsible for the armament. Whenever we flew‚ it was my job to go out to the airplane‚ and check all the turrets to see that they operated. Check all the guns to see that they operated‚ and to check the bombs to see that they were properly loaded and that the pins were in them to secure the arming mechanisms‚ so that they wouldn’t arm during takeoff or in flight until they were over the target.

I have a record of flying‚ my time in the air during the service. Military record of it. In May I was in Casper‚ Wyoming. We left Laredo‚ Texas. We were assigned to a crew‚ and traveled together then as a crew. It was Lincoln‚ Nebraska‚ where we were assigned a crew. Sent then to Casper‚ Wyoming.

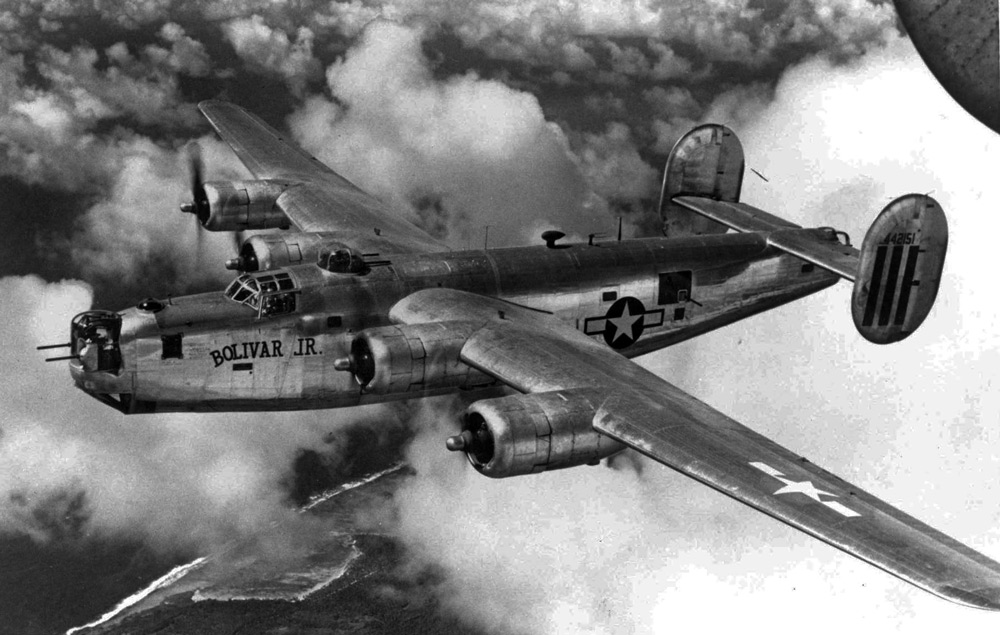

b–24 bomber (USAF museum‚dayton, ohio)

b–24 bomber (USAF museum‚dayton, ohio)

We were told we were trained as a crew‚ and we were also assigned to a Liberator bomber. B–24. In Casper‚ Wyoming‚ that was putting it all together then as a crew. Actually hands on flying. We flew almost every day. For the pilot and the copilot it was practicing take–offs and landings. For the navigator it was practice charting a course and plotting where we were. The radio operator was taking messages and instructions. The rest of us were checking out the guns. Before we took off‚ we’d go through the whole routine‚ just like we were going on a bombing mission. Check out our guns and our turrets and armament and so on.

Part of the objective was for each one of us to get more familiar with the job we’d actually be doing‚ and the other part of it was learning to function as a team. Learning each other’s personalities‚ how we were wired together‚ put together‚ whether or not there were any real conflicts‚ people that couldn’t get along together.

I was the armorer/gunner. As far as I know‚ they had at least one armorer/gunner in each bomber.

We were in an Air Force base just outside of Casper‚ Wyoming‚ and we got to go in town. It was a small western town and people were friendly. The food was good on the airbase. They had a twenty–four hour mess hall on the airbase for flight crews. We flew at all times of the day and night. You never knew when you were going to be flying. They had a twenty–four hour mess hall. You could go in and eat anytime you wanted to eat‚ and the food was good.

The climate was good there. It was just routine operations. We had a chance to go in town and go up in the mountains—see some of the country around Casper. Go horseback riding. I think maybe once a week we could get off the airbase for a day. I don’t remember any bad experiences there.

I got along fine with the crew. During the process we had the one guy I told you about the other day. He was a gunner‚ and he just wasn’t very cooperative. He was a nice guy‚ but he just didn’t care about...on the crew‚ you not only had to take care of yourself‚ but you had to look around. Suppose when you’re flying at altitude if somebody’s oxygen mask‚ or something happened to an oxygen system‚ the hose pulled loose. Their life depended on other people around constantly taking a look to see where everybody else was‚ at their position‚ if they were OK. He just didn’t seem to bother with this kind of stuff. So he was the guy that when we left Casper‚ we said we’re not going to fly in combat with you‚ cause you’d get us all killed. Apparently the pilot requested that he be taken off the crew. We had another person then assigned to the crew.

b–24 liberator bomber

b–24 liberator bomber

Pilot‚ co–pilot‚ navigator and bombardier are your basic crew. That all changed after we got overseas and flying missions‚ but that was later. On the basic crew‚ we had four officers and then we had a nose turret operator‚ gunner who was the nose turret operator‚ and the engineer flew the top turret‚ and then there were two waist gunners and a tail gunner. At the time we were in training‚ they had stopped using the ball turrets at the bottom of the plane. We didn’t have a ball turret operator.

I got along fine with the officers. They were not the typical Army officers. They were interested in people doing their job. They didn’t care much about military courtesies. We used to line up‚ the enlisted men would line up‚ really come to attention and salute the pilot when he came out‚ and he’d grin and say “Aw‚ knock it off‚ you guys.” We responded to each other as people on a team. They weren’t interested in the military courtesies kind of stuff‚ as long as everybody did their job.

The crew socialized off the plane. We did not socialize a great deal with the officers‚ because they had an officers’ club and lived in different quarters‚ but the crew‚ we buddied together. It was a part of cementing the crew together. We all went to town together and some of the people had different interests and they would go after their own interests‚ but then we’d get back together as a crew. During a good part of the time‚ both going and coming on passes‚ we traveled together.

Frequently in a military town there were all kinds of people around that were looking for an easy way to make a buck off the soldiers. It was our habit‚ or developed the habit‚ if we went to town and went in a bar there would probably be a couple of us go up to the bar and sit at the bar. A couple of guys would go over in a corner and sit someplace‚ and once in a while keep an eye on each other.

I remember one incident where‚ I think it was after we left Casper‚ we went into a bar one night. This was after we got over to England. There was two of us‚ the radio operator and the engineer were sitting up at the bar having an English beer. A couple–three of the rest of us were over at a table. This old gal walked up‚ put her arms around the engineer and the radio operator and talking and she rubbing her hand on their sides. And she dropped her hand down and rubbed it across their rear and flipped the button on their...and so two of us got up and walked over to the bar. They got real upset because we rooted this gal out. “What’s the matter with you guys? We were having a good time.” Then after we got her away from them we explained what was happening. One of them had had a little bit too much to drink. He was all for getting up and going after her and kicking the shit out of her.

Another time we went into a bar‚ we had a tail gunner who was a little bitty fellow. He was at the bar drinking‚ and there was some great big lout come in and started an argument with him‚ and was going to haul off and hit him. The radio operator was bigger than I am‚ but he wasn’t quite as tall‚ and the two of us got up and walked over to the tail gunner and said “Les‚ are you having any problems?” That guy took a look at both of us and turned around and walked away. We had that same sort of thing going when we were on the plane and when we were off the plane. Going to town or other places.

I don’t know‚ maybe it was because‚ I think maybe our average age was a little bit higher than some of the crews‚ but we had one of the best crews. I have more than just my opinion for that. After we got to England and flew– a few missions our pilot was picked to be a lead pilot. That not only reflected on his ability as a pilot‚ but on the rest of the crew as well.

We went from Casper‚ Wyoming‚ to Topeka‚ Kansas. There we were told that we would be assigned a bomber and that we were leaving immediately to go overseas and that we would not get a furlough home. There was I think three of us on the crew in the same situation that had been in the service since the time we were inducted. Up to that point we had never had a furlough. The most time we’d had off was the one day pass. They also told us‚ that if any one of us went AWOL that the whole crew would be sent over in an infantry boat. They made a great point of telling us how infantry soldiers did not like the Air Force. That it would be a very unpleasant experience‚ so none of us went AWOL‚ but we were all pissed off.

From January of 1943 until mid–July of 1944‚ I’d been in service all that time‚ and was sent overseas without a chance to come home on a furlough. I was really pissed off at the United States government. Closest I got to Ohio was going over Cleveland in a B–24 bomber. So we ended up getting on the bomber with a case of whiskey‚ and we stayed pretty well lubricated on the way‚ except the pilot‚ co–pilot and the navigator. They didn’t drink while they were flying. But the rest of us did. We didn’t have anything to do other than ride.

We flew the B–24 bomber to Manchester‚ New Hampshire. Stayed overnight in Manchester‚ New Hampshire. The next day we flew to Goose Bay‚ Labrador. We landed at Goose Bay and stayed there a couple of days. Then we took off and flew to Reykjavik in Iceland and we stayed overnight one night there‚ and we flew from Reykjavik to Valley‚ Wales. And in Valley‚ Wales‚ we were separated.

They took the bomber away from us. It was sent to‚ I’ve forgotten the airbase in England‚ near Manchester. They modified them over there. One of the things they did‚ the bombers come out of the factory and they had a pee tube in the bomb bay. You could go over there and take a leak in this contraption and it had a hose and run the pee outside of the airplane. Well‚ what happened was‚ when anybody peed in the darn thing‚ it went under the plane and come up over the tail and splattered the window on the tail turret. So if somebody peed in the airplane‚ the tail gunner couldn’t see out. Apparently they had known this for a hell of a long time‚ but they still put those things in the airplanes. Well‚ first thing they did when they got them overseas was to jerk those things out. You had an ammunition can or something else to pee in if you had to go to the restroom. Some of our missions‚ the longest one I was on was nine hours‚ and so it was not unusual that you’d have to take a leak or go in the air. It was in an ammunition box. You didn’t pee outside or run it outside the airplane.

All we were doing was ferrying the craft over. I don’t remember that we ever saw that airplane again. No‚ we went in going individually. We flew individually. The navigator had to be on the ball. Fortunately‚ we had a good navigator. He was right on the mark all the time. All we know was that we had orders cut for England. We knew we were taking the bomber and that we were going to England.

I don’t know that there was any big deal about it. It was understood on our crew that the pilot expected each one of us to do our job and he didn’t want to screw around with us. All he wanted to know was that each person was doing what they were supposed to do and that was it. He didn’t make a big deal about it. I don’t think he said very much. He was just the kind of a guy‚ that he was a perfectionist in his job and he had the kind of the attitude. He just expected everybody else to do everything the way they were supposed to do and I don’t remember that they gave us any pep talk.

I never felt a whole lot of flag waving made that much difference to me. So there may have been some that I wasn’t aware of‚ but the emphasis was on doing a good job. The emphasis was on knowing what to do and when to do it. A lot of training from people who had been in combat‚ explaining in detail what would happen under different circumstances. What happened‚ what to do when you bailed out‚ and that training saved my life. They covered just about everything that was possible to happen to you‚ and what to do and how to do it. There were instructions on how to conduct yourself if you were taken prisoner‚ and all that kind of stuff. But it was just training for the job that we were going to do‚ and I don’t remember that there was a lot of rah rah about it.

You know‚ like for football teams and basketball‚ I understand in some units in the military there was a lot of that. To give you an instance of our pilot’s attitude. We had different people flying with us at different times‚ and we had a bombardier that we’d never seen before flying with us on one of our training flights. I don’t remember how he come to be on the airplane. Our bombardier wasn’t on the plane that day‚ something happened.

Anyhow‚ he was a second lieutenant‚ and he was up in the compartment where the engineer and the radio operator were‚ his back to the pilot and co-pilot. There was a message coming over the radio and there was a lot of static and the radio operator was really concentrating. This lieutenant decided he wanted to ask the radio operator a question. So he spoke to him and the radio operator paid no attention to him. He went ahead writing down the message. and so this lieutenant reached over and grabbed him by the arm. The radio operator took his hand and smacked it away. Really hit him. Well‚ when we got down on the ground‚ this bombardier went over to the pilot and told him what had happened‚ that the radio operator had hit him. The pilot said‚ “Look‚ you better leave him alone or he’ll kick the shit out of you‚” and turned around and walked off. So that kind of gives you some kind of clue as to what kind of a person the pilot was. He was interested in people doing their job.

hethel‚ england

hethel‚ england

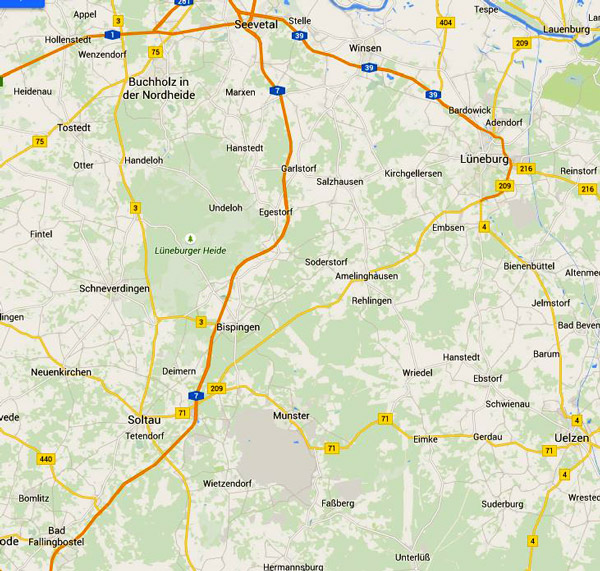

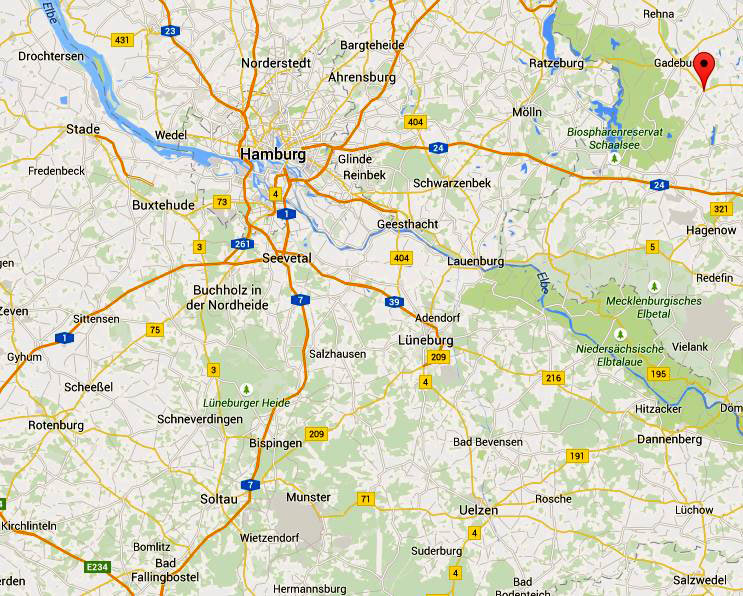

From Wales we were separated. The pilot and the co–pilot and the navigator and the bombardier went off. Our understanding was that they got some specialized training about flying in England and Europe. I never did know‚ never did talk to them about what kind of training they went through. But the gunners got shipped over Ireland to Newcastle. We spent a couple of weeks over there in a gunnery school. I don’t recall that we did any shooting to amount to anything‚ but we spent a lot of time in terms of what to expect in the European Theater‚ in terms of flying missions over Germany‚ what to expect as to our duties as gunners on bombers. It was after that then we were rejoined with the crew‚ and we were assigned to a base called Hethel.

As far as I know we were under the Eighth Air Force. We were assigned to the 389th Bomb Group. The 566th Squadron. We were stationed at a base called Hethel‚ which is near Wyndham. It’s not on the map. It was just an airbase near Wyndham. Wyndham was about eight miles southwest of Norwich. That whole East Anglia area was covered with bomber bases. B–17’s and B–24’s. We rejoined the rest of our crew on the airbase at Hethel. The best I can remember‚ we did not know where the hell we were going until we got there. We were identified as a crew‚ I’m sure of that. But we weren’t told. I don’t know whether the pilot or the officers knew where they were going. But we didn’t know where we were even when we got there.

I was a staff sergeant. Most gunners were staff sergeants. I was trying to think about it today. I think there were three squadrons on the base‚ but I can’t be sure. I’d have to go dig it out. I don’t recall exactly when I got to Hethel. It was probably either the latter part of July or around the first of August. We flew our first mission in August of ’44.

We had single story tar paper shacks there‚ with a little pot–bellied stove‚ couple of pot–bellied stoves‚ and it was typical English countryside. The officers would be in the officers quarters. When we got there‚ there was all kind of harassment. People sat and watched us get off the trucks and they were yelling “fresh meat” and all kind of horror stories and so on. I guess it happened to every new crew that come on‚ that sort of thing.

There was a low level of military discipline. The whole attitude or their main concern was that people did a good job. Most of the time they didn’t screw around harassing you about your uniform or military saluting. Most of the time if you saluted the officers on a crew‚ they didn’t like it. They would prefer you didn’t. They didn’t screw around with that kind of stuff. Once in a while somebody would arrive from the states in an administrative position and they would try and shape everybody up‚ but that didn’t last too long. Apparantly in some branches of the service they felt that that was an absolute must‚ that the military couldn’t function without it.

I don’t know whether this existed throughout the Air Force. My impression that it did. The emphasis on military discipline as such was not as big a concern to people in the Air Force as it was to the other branches of the service. The emphasis was on doing what you were supposed to do and doing a good job. I personally was‚ looking back on it‚ a whole lot happier in the Air Force than I would have been in any other branch of the service‚ because I don’t have the same feeling about military discipline. I understand the importance of discipline‚ but some of that stuff was what I always termed chickenshit. Just symbolic and didn’t amount to that much.

Our first mission‚ on August 18‚ 1944‚ was to Metz‚ France‚ an airfield. We got up real early‚ probably four–thirty or five. Part of it was depending on where the mission was going. Normally‚ we would get up‚ it would be in the wee hours of the morning. I remember most of the time it was dark when we went out to the airplane. We’d get up and stagger off to the mess hall and get something to eat. We went to the mess hall to eat‚ and then go to briefing and then go out and get the airplane ready to take off. You go draw your parachute and your equipment on the way to the aircraft.

At briefing they would show you the target and they had a great big picture on the wall of the actual target. They had a map of Germany‚ and here was the line of flight‚ and they would plot the line of flight to the target in a way so as to fly far away from known installations of flak batteries‚ guns on the ground. In other words‚ you wouldn’t fly close to any big cities that have a lot of guns around them. You fly where you would get the least flak damage. I think maybe some of the planning of the flight route also had to do with confusing the Germans where they were headed. Then you got to a place they called the IP.

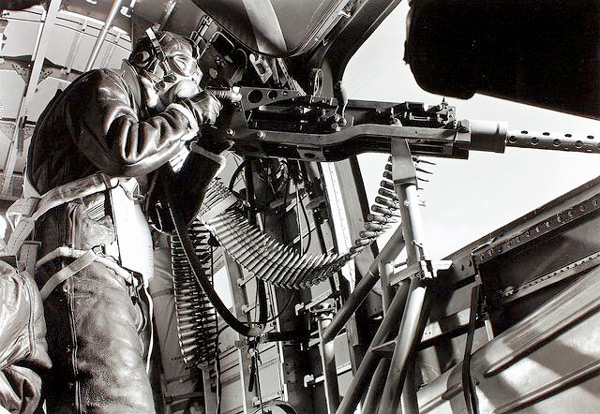

waist gunner in B–24

waist gunner in B–24

You turned on the IP‚ and the bombardier took over the bomb sight‚ and from there on you flew straight and level. Up until that point you could take evasive action if someone was shooting at you‚ but when you turned on the bomb run‚ why then you gritted your teeth and stayed right on the route‚ until the bombs were dropped. Then when the bombs left the bomb bay it was‚ “The hell with Uncle Sam— we’re goin’ home!” From there on take evasive action‚ the objective was to get out of there as quick as possible.

The first mission we flew‚ as I remember‚ there was no action to speak of. It was an air field the Germans were using in France. It was one of the shorter missions. My records show seven hours and fifty minutes.

I think we had some chewing gum‚ maybe some candy. I don’t remember taking sandwiches. Maybe we did have sandwiches. I don’t remember that.

One of the tough parts of flying a mission‚ sometimes the worst part of the mission was taking off. Frequently in England when we took off there was heavy cloud. I think one time there were fifteen hundred bombers over Germany in one day. There were all these bombers forming over East Anglia. When you took off there was a flight pattern that the pilot was to fly‚ but for several minutes you were going through solid fog‚ and there were clouds. Everybody was staring out the window with a thumb on the mike switch looking for other planes‚ somebody being off course or something happening—a traumatic experience until we got above the clouds. Because the planes were all flying around up there until they got into formation.

It was only after they were all formed up then‚ did the whole bomber string start for Europe. Occasionally there was a collision in the air. Planes run into each other. Occasionally a bomber would explode on the way over the Channel. Couple of times I saw a bomber explode. It was probably somebody lit a cigarette without checking for gas fumes. You could smoke in the airplanes when you were at low altitudes‚ but you didn’t dare light a cigarette until the engineer had checked the airplane to see if there were any fuel fumes. We always figured that some idiot had lit a cigarette or attempted to light a cigarette and that ignited the fumes. We were setting there looking out—all of a sudden there was a “poof”—a big flash in the sky and there was pieces‚ circling‚ falling down.

But the tedious part of flying was the part of taking off‚ and then over the target area‚ then coming back home. Sometimes when you come back home you had to land in fog and clouds. Sometimes it would be solid cover and the only thing you could do was divert somewhere or go somewhere else where there wasn’t clouds.

One time we came back and our base was fogged in. There were bombers scattered all over‚ directed to go to all different places. We flew north‚ and when we got to the airbase we were supposed to land at—it was a RAF airbase. When we got there there was a bomber cracked up on one runway‚ and it was clouded over‚ clouds drifting over the airbase. We were practically out of gas. We circled the airbase several times. All of a sudden there was a little opening come in the clouds. Our pilot stood the plane practically on its side‚ he dropped it several hundred feet just snap‚ and got it on the ground. Had he missed that opportunity we would have ended up crashing‚ because a few minutes after we landed it clouded over in solid clouds.

When we got out of the airplane‚ he had on coveralls and he was just sopping wet from head to foot‚ sweating. It was cold—this was in the winter time when that happened—and the rest of us were freezing. We had a lot of laughing‚ talking about him being wet with sweat. He had the responsibility of the whole crew of people in getting that bomber on the ground‚ and one runway with a wrecked aircraft on it. We really felt good about having that man as our pilot. He seemed to be a fellow who became a part of the airplane when he flew it. That made the difference.

b–24 bomber formation

b–24 bomber formation

It was a thrill to see all that many airplanes in the sky. It was also a marvelous miracle that they could get that many airplanes off the ground in the air and formed and fly over Germany. I’ve often thought it must have been a terrifying sight to the Germans to see all those bombers coming across. It was a thrill to see that many bombers.